Territorial Economic Accounts for American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands

New Estimates of GDP for 2017, New Estimates of GDP by Industry and Compensation by Industry for 2016

In collaboration with the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Insular Affairs (OIA) and with staff from the territorial governments, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) produces annual economic accounts for American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The OIA provides funding for the work and facilitates interactions between BEA and the territorial governments.1

The purpose of this ongoing project is to provide data users with comprehensive, objective measures of economic activity for these four U.S. territories. Consistent measures of economic activity are critical for understanding the territorial economies and how they have developed over time. Without such measures, it is difficult for businesses and governments to make informed economic and financial planning decisions and for policymakers to assess the impacts of their decisions on growth. For the United States, BEA produces gross domestic product (GDP) and other related economic measures as part of its National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs); however, these estimates cover only the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Transactions with the territories are classified as transactions with the “rest-of-the-world.”

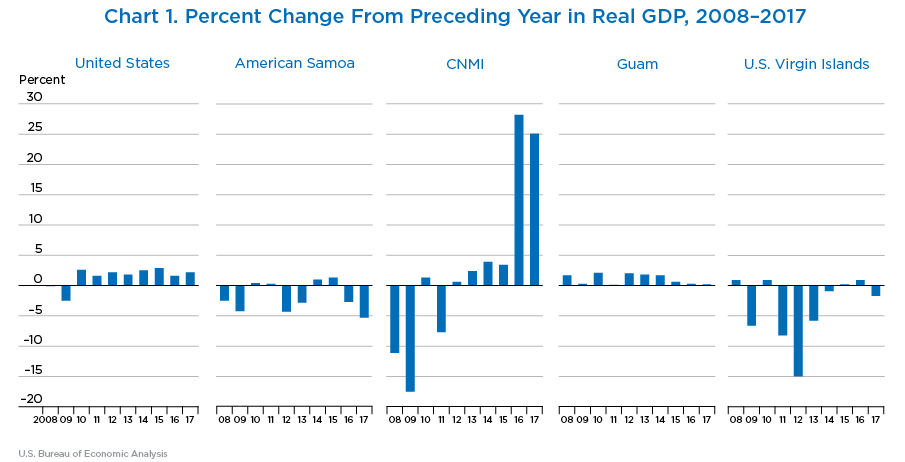

This year, BEA released new estimates of GDP for 2017 and revised estimates for 2013–2016.2 These estimates are shown in chart 1. For comparison, real GDP growth for the United States (excluding the territories) is also shown.

Highlights of the latest GDP estimates for each territory are described below.

American Samoa

Real GDP decreased 5.3 percent in 2017 (table A.1.3).

- The decline in the American Samoa economy reflected decreases in exports of goods and government spending.

- Exports of canned tuna and related products declined significantly in 2017, following the closure of one of two tuna canneries located in American Samoa.

- Government spending decreased, reflecting a continued decline in investment spending by the territorial government (table A.1.4).3 Major infrastructure projects, including the Satala Power Plant and the Ta’u solar microgrid, reached their final stages in late 2016.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 520 | 563 | 678 | 576 | 574 | 644 | 641 | 643 | 661 | 653 | 634 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 383 | 407 | 398 | 402 | 414 | 424 | 447 | 455 | 444 | 446 | 460 |

| Goods | 195 | 208 | 196 | 197 | 188 | 189 | 214 | 217 | 207 | 203 | 206 |

| Durable goods | 23 | 27 | 24 | 25 | 23 | 23 | 29 | 35 | 31 | 30 | 26 |

| Nondurable goods | 171 | 181 | 172 | 172 | 166 | 167 | 185 | 183 | 177 | 174 | 180 |

| Services | 189 | 202 | 207 | 211 | 229 | 242 | 242 | 248 | 246 | 252 | 264 |

| Net foreign travel | −1 | −3 | −5 | −5 | −4 | −6 | −10 | −11 | −10 | −9 | −11 |

| Private fixed investment | 41 | 46 | 38 | 49 | 51 | 53 | 60 | 66 | 53 | 51 | 51 |

| Change in private inventories | −8 | −17 | −6 | −5 | −3 | 0 | 5 | 31 | 24 | 44 | 41 |

| Net exports of goods and services | −116 | −113 | −26 | −174 | −225 | −161 | −184 | −252 | −230 | −208 | −224 |

| Exports | 505 | 641 | 530 | 364 | 335 | 482 | 457 | 426 | 427 | 427 | 364 |

| Goods | 487 | 621 | 510 | 341 | 313 | 456 | 433 | 400 | 401 | 401 | 336 |

| Services | 17 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 26 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 28 |

| Imports | 621 | 754 | 556 | 537 | 559 | 643 | 641 | 678 | 657 | 634 | 588 |

| Goods | 571 | 698 | 508 | 489 | 509 | 588 | 587 | 616 | 594 | 572 | 527 |

| Services | 50 | 56 | 49 | 48 | 50 | 55 | 54 | 63 | 63 | 62 | 60 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

220 | 241 | 275 | 304 | 337 | 329 | 313 | 344 | 370 | 320 | 306 |

| Federal | 17 | 20 | 30 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 24 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Territorial | 203 | 220 | 244 | 281 | 314 | 306 | 291 | 319 | 345 | 294 | 281 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 727 | 708 | 678 | 681 | 683 | 653 | 635 | 641 | 649 | 632 | 598 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 420 | 410 | 398 | 381 | 364 | 357 | 369 | 372 | 371 | 375 | 374 |

| Goods | 216 | 212 | 196 | 187 | 170 | 165 | 183 | 185 | 178 | 175 | 171 |

| Durable goods | 27 | 27 | 24 | 24 | 21 | 19 | 25 | 29 | 25 | 25 | 22 |

| Nondurable goods | 190 | 185 | 172 | 163 | 149 | 146 | 158 | 156 | 152 | 151 | 150 |

| Services | 207 | 202 | 207 | 200 | 198 | 197 | 195 | 196 | 201 | 206 | 210 |

| Net foreign travel | −3 | −4 | −5 | −6 | −4 | −6 | −8 | −9 | −8 | −7 | −7 |

| Private fixed investment | 40 | 45 | 38 | 50 | 52 | 51 | 55 | 59 | 47 | 44 | 44 |

| Change in private inventories | −7 | −11 | −6 | −4 | −2 | 0 | 4 | 25 | 23 | 43 | 37 |

| Net exports of goods and services | 52 | 36 | −26 | −48 | −67 | −67 | −84 | −121 | −114 | −104 | −128 |

| Exports | 678 | 675 | 530 | 446 | 394 | 412 | 410 | 428 | 460 | 454 | 358 |

| Goods | 658 | 654 | 510 | 424 | 372 | 388 | 387 | 404 | 437 | 432 | 333 |

| Services | 20 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 23 |

| Imports | 626 | 639 | 556 | 494 | 460 | 479 | 494 | 549 | 575 | 558 | 486 |

| Goods | 575 | 586 | 508 | 450 | 417 | 433 | 448 | 497 | 523 | 508 | 436 |

| Services | 51 | 52 | 49 | 45 | 44 | 47 | 46 | 51 | 52 | 50 | 50 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

227 | 239 | 275 | 290 | 309 | 297 | 278 | 299 | 321 | 275 | 258 |

| Federal | 18 | 20 | 30 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Territorial | 209 | 219 | 244 | 268 | 287 | 276 | 258 | 276 | 297 | 252 | 236 |

| Addenda: | |||||||||||

| Population (thousands)1 | 64.8 | 65.1 | 62.4 | 55.5 | 56.0 | 56.5 | 57.0 | 57.5 | 58.1 | 58.6 | 58.7 |

| Per capita real GDP (chained dollars) | 11,219 | 10,876 | 10,865 | 12,270 | 12,196 | 11,558 | 11,140 | 11,148 | 11,170 | 10,785 | 10,187 |

- BEA estimates based on data from the American Samoa Department of Commerce and the U.S. Census Bureau.

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | −2.5 | −4.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −4.3 | −2.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | −2.7 | −5.3 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | −2.4 | −2.9 | −4.3 | −4.6 | −2.0 | 3.5 | 0.8 | −0.3 | 1.2 | −0.2 |

| Goods | −1.9 | −7.8 | −4.6 | −9.3 | −2.6 | 10.8 | 1.2 | −4.0 | −1.3 | −2.5 |

| Durable goods | 3.0 | −12.7 | 0.9 | −14.6 | −5.7 | 26.8 | 17.4 | −12.1 | −2.9 | −12.6 |

| Nondurable goods | −2.5 | −7.1 | −5.4 | −8.5 | −2.2 | 8.6 | −1.4 | −2.4 | −1.0 | −0.8 |

| Services | −2.3 | 2.5 | −3.4 | −0.9 | −0.5 | −1.2 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| Net foreign travel | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Private fixed investment | 13.5 | −15.9 | 30.9 | 5.2 | −2.3 | 8.0 | 6.9 | −20.7 | −5.4 | −1.0 |

| Change in private inventories | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Net exports of goods and services | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Exports | −0.4 | −21.4 | −15.8 | −11.8 | 4.7 | −0.5 | 4.4 | 7.6 | −1.3 | −21.2 |

| Goods | −0.6 | −22.1 | −16.8 | −12.2 | 4.1 | −0.2 | 4.4 | 8.2 | −1.3 | −22.8 |

| Services | 4.9 | −0.2 | 5.4 | −5.8 | 13.0 | −6.2 | 4.9 | −1.7 | −2.6 | 5.6 |

| Imports | 2.1 | −12.9 | −11.1 | −6.9 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 11.1 | 4.7 | −2.9 | −12.9 |

| Goods | 1.9 | −13.4 | −11.4 | −7.4 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 11.0 | 5.1 | −2.9 | −14.2 |

| Services | 3.5 | −7.3 | −8.0 | −2.1 | 7.3 | −2.3 | 12.1 | 1.2 | −2.8 | −1.0 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

5.4 | 15.0 | 5.6 | 6.6 | −4.1 | −6.4 | 7.5 | 7.4 | −14.3 | −6.0 |

| Federal | 12.3 | 49.5 | −28.1 | 1.4 | −5.6 | −3.6 | 11.0 | 5.0 | −0.7 | −2.1 |

| Territorial | 4.8 | 11.8 | 9.8 | 7.0 | −4.0 | −6.6 | 7.2 | 7.6 | −15.3 | −6.3 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent change: | ||||||||||

| Gross domestic product | −2.5 | −4.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −4.3 | −2.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | −2.7 | −5.3 |

| Percentage points: | ||||||||||

| Personal consumption expenditures | −1.78 | −1.83 | −2.84 | −3.32 | −1.37 | 2.26 | 0.57 | −0.20 | 0.77 | −0.10 |

| Goods | −0.69 | −2.56 | −1.50 | −3.27 | −0.81 | 3.17 | 0.39 | −1.34 | −0.39 | −0.77 |

| Durable goods | 0.13 | −0.54 | 0.03 | −0.66 | −0.21 | 0.94 | 0.80 | −0.65 | −0.13 | −0.56 |

| Nondurable goods | −0.82 | −2.02 | −1.54 | −2.61 | −0.59 | 2.23 | −0.41 | −0.68 | −0.26 | −0.21 |

| Services | −0.83 | 0.81 | −1.18 | −0.36 | −0.19 | −0.45 | 0.27 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.78 |

| Net foreign travel | −0.25 | −0.08 | −0.16 | 0.30 | −0.38 | −0.45 | −0.10 | 0.22 | 0.18 | −0.11 |

| Private fixed investment | 0.99 | −1.14 | 1.89 | 0.44 | −0.19 | 0.67 | 0.65 | −2.12 | −0.43 | −0.08 |

| Change in private inventories | −0.98 | 0.90 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.83 | 3.93 | −0.42 | 3.05 | −0.84 |

| Net exports of goods and services | −2.99 | −7.80 | −1.70 | −0.80 | −0.97 | −3.33 | −7.86 | 0.05 | 1.95 | −1.40 |

| Exports | −0.46 | −22.11 | −12.25 | −7.65 | 2.96 | −0.36 | 2.99 | 4.81 | −0.87 | −14.19 |

| Goods | −0.62 | −22.11 | −12.43 | −7.42 | 2.49 | −0.12 | 2.79 | 4.88 | −0.76 | −14.41 |

| Services | 0.16 | −0.01 | 0.18 | −0.23 | 0.47 | −0.25 | 0.19 | −0.07 | −0.10 | 0.22 |

| Imports | −2.53 | 14.31 | 10.55 | 6.86 | −3.93 | −2.97 | −10.84 | −4.77 | 2.81 | 12.78 |

| Goods | −2.19 | 13.69 | 9.88 | 6.67 | −3.33 | −3.17 | −9.80 | −4.65 | 2.54 | 12.69 |

| Services | −0.33 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.18 | −0.60 | 0.20 | −1.05 | −0.11 | 0.27 | 0.10 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

2.21 | 5.67 | 2.58 | 3.58 | −2.27 | −3.24 | 3.71 | 3.95 | −7.99 | −2.91 |

| Federal | 0.40 | 1.58 | −1.40 | 0.06 | −0.21 | −0.12 | 0.37 | 0.19 | −0.03 | −0.08 |

| Territorial | 1.81 | 4.09 | 3.98 | 3.52 | −2.06 | −3.12 | 3.34 | 3.76 | −7.97 | −2.83 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 11.1 | 25.7 | −15.4 | −0.6 | 17.3 | 2.3 | −0.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.6 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 8.9 | 0.8 | 5.4 | 7.8 | 4.7 | 1.8 | 1.0 | −2.2 | −0.6 | 3.2 |

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 520 | 563 | 678 | 576 | 574 | 644 | 641 | 643 | 661 | 653 |

| Private industries | 365 | 404 | 514 | 389 | 389 | 450 | 450 | 455 | 465 | 457 |

| Manufacturing | 77 | 112 | 163 | 41 | 21 | 89 | 93 | 77 | 92 | 89 |

| Nonmanufacturing | 288 | 291 | 351 | 348 | 368 | 361 | 358 | 378 | 374 | 367 |

| Government | 156 | 160 | 165 | 187 | 185 | 195 | 190 | 188 | 195 | 196 |

| Federal | 14 | 16 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 19 |

| Territorial | 142 | 144 | 146 | 169 | 168 | 177 | 172 | 171 | 177 | 178 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 727 | 708 | 678 | 681 | 683 | 653 | 635 | 641 | 649 | 632 |

| Private industries | 568 | 544 | 514 | 501 | 514 | 474 | 464 | 478 | 485 | 469 |

| Manufacturing | 204 | 205 | 163 | 143 | 132 | 138 | 135 | 140 | 160 | 156 |

| Nonmanufacturing | 366 | 345 | 351 | 353 | 365 | 331 | 324 | 334 | 330 | 318 |

| Government | 163 | 166 | 165 | 177 | 170 | 176 | 168 | 162 | 163 | 161 |

| Federal | 14 | 17 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Territorial | 148 | 149 | 146 | 160 | 154 | 160 | 151 | 146 | 147 | 145 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | −2.5 | −4.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −4.3 | −2.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | −2.7 |

| Private industries | −4.2 | −5.5 | −2.4 | 2.5 | −7.7 | −2.2 | 3.1 | 1.4 | −3.3 |

| Manufacturing | 0.4 | −20.3 | −12.3 | −7.9 | 4.9 | −1.9 | 3.3 | 14.5 | −2.7 |

| Nonmanufacturing | −5.7 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 3.4 | −9.3 | −2.2 | 3.1 | −1.3 | −3.5 |

| Government | 1.7 | −0.6 | 7.8 | −4.2 | 3.4 | −4.3 | −3.9 | 0.8 | −1.0 |

| Federal | 14.7 | 10.7 | −7.6 | −4.4 | −0.8 | 4.8 | −4.1 | −1.0 | 1.8 |

| Territorial | 0.4 | −1.8 | 9.7 | −4.1 | 3.8 | −5.2 | −3.8 | 1.0 | −1.3 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent change: | |||||||||

| Gross domestic product | −2.5 | −4.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −4.3 | −2.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | −2.7 |

| Percentage points: | |||||||||

| Private industries | −3.03 | −4.14 | −1.81 | 1.64 | −5.34 | −1.51 | 2.17 | 1.01 | −2.35 |

| Manufacturing | 0.07 | −4.98 | −2.21 | −0.47 | 0.40 | −0.27 | 0.43 | 1.75 | −0.37 |

| Nonmanufacturing | −3.10 | 0.84 | 0.40 | 2.11 | −5.74 | −1.24 | 1.74 | −0.74 | −1.98 |

| Government | 0.48 | −0.14 | 2.14 | −1.38 | 1.02 | −1.30 | −1.17 | 0.25 | −0.31 |

| Federal | 0.38 | 0.28 | −0.23 | −0.14 | −0.02 | 0.13 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Territorial | 0.11 | −0.42 | 2.37 | −1.24 | 1.04 | −1.43 | −1.05 | 0.28 | −0.36 |

Note. Percentage-point contributions do not sum to the percent change in real gross domestic product because of rounding and differences in source data used to estimate GDP by industry and the expenditures measure of real GDP.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total compensation | 265 | 274 | 271 | 270 | 262 | 272 | 279 | 297 | 311 | 312 |

| Private industries | 125 | 131 | 125 | 97 | 97 | 103 | 107 | 119 | 126 | 130 |

| Manufacturing | 52 | 59 | 53 | 31 | 27 | 40 | 42 | 46 | 54 | 54 |

| Nonmanufacturing | 73 | 72 | 71 | 66 | 70 | 63 | 65 | 74 | 72 | 75 |

| Government | 140 | 143 | 147 | 173 | 164 | 169 | 171 | 178 | 185 | 183 |

| Federal | 13 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 18 |

| Territorial | 127 | 127 | 129 | 156 | 148 | 152 | 154 | 161 | 167 | 165 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI)

Real GDP increased 25.1 percent in 2017 (table B.1.3).

- The growth in the CNMI economy primarily reflected a continued increase in gaming industry activity.

- Exports of services was the largest contributor to economic growth in 2017, reflecting growth in visitor spending, particularly on casino gambling (table B.1.4).

- Business spending on construction and equipment remained at historically high levels, supported by continued development of the casino resort on Saipan.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 938 | 939 | 795 | 799 | 733 | 751 | 782 | 845 | 931 | 1,250 | 1,593 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 480 | 504 | 431 | 442 | 451 | 469 | 494 | 520 | 526 | 551 | 597 |

| Goods | 358 | 387 | 332 | 354 | 366 | 399 | 424 | 451 | 453 | 462 | 523 |

| Durable goods | 137 | 142 | 119 | 130 | 132 | 143 | 166 | 186 | 194 | 202 | 227 |

| Nondurable goods | 222 | 245 | 213 | 224 | 234 | 256 | 257 | 265 | 258 | 259 | 296 |

| Services | 409 | 427 | 381 | 398 | 378 | 427 | 460 | 498 | 556 | 965 | 1,214 |

| Net foreign travel | −287 | −310 | −283 | −309 | −293 | −357 | −390 | −429 | −483 | −876 | −1,140 |

| Private fixed investment | 79 | 83 | 85 | 77 | 74 | 79 | 87 | 123 | 198 | 327 | 301 |

| Net exports of goods and services | 47 | 29 | −47 | −70 | −132 | −98 | −111 | −110 | −130 | 0 | 296 |

| Exports | 627 | 488 | 312 | 335 | 317 | 380 | 414 | 451 | 504 | 903 | 1,170 |

| Goods | 333 | 172 | 23 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 13 | 19 | 23 |

| Services | 293 | 316 | 289 | 316 | 300 | 364 | 397 | 436 | 491 | 883 | 1,148 |

| Imports | 579 | 459 | 360 | 405 | 449 | 478 | 525 | 561 | 633 | 902 | 874 |

| Goods | 498 | 394 | 307 | 346 | 384 | 409 | 449 | 477 | 488 | 636 | 632 |

| Services | 81 | 66 | 53 | 59 | 65 | 69 | 76 | 84 | 145 | 267 | 242 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

332 | 324 | 327 | 349 | 340 | 301 | 312 | 312 | 336 | 372 | 400 |

| Federal | 13 | 15 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 29 | 26 | 26 |

| Territorial | 319 | 308 | 306 | 327 | 318 | 279 | 292 | 290 | 308 | 346 | 374 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 1,084 | 964 | 795 | 806 | 744 | 748 | 766 | 795 | 822 | 1,054 | 1,319 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 516 | 509 | 431 | 444 | 430 | 440 | 463 | 483 | 499 | 518 | 545 |

| Goods | 395 | 400 | 332 | 349 | 338 | 363 | 388 | 403 | 414 | 422 | 463 |

| Durable goods | 149 | 149 | 119 | 127 | 121 | 131 | 153 | 169 | 185 | 190 | 203 |

| Nondurable goods | 246 | 251 | 213 | 222 | 217 | 232 | 234 | 235 | 230 | 233 | 260 |

| Services | 434 | 433 | 381 | 389 | 354 | 390 | 413 | 435 | 485 | 812 | 1,006 |

| Net foreign travel | −313 | −324 | −283 | −294 | −263 | −313 | −336 | −353 | −400 | −732 | −945 |

| Private fixed investment | 80 | 82 | 85 | 78 | 72 | 76 | 84 | 119 | 193 | 320 | 292 |

| Net exports of goods and services | 147 | 48 | −47 | −56 | −82 | −52 | −64 | −76 | −148 | −105 | 138 |

| Exports | 747 | 476 | 312 | 320 | 284 | 333 | 357 | 373 | 415 | 721 | 920 |

| Goods | 396 | 138 | 23 | 19 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 18 | 20 |

| Services | 320 | 331 | 289 | 300 | 269 | 319 | 342 | 359 | 402 | 702 | 898 |

| Imports | 600 | 428 | 360 | 376 | 367 | 384 | 421 | 449 | 563 | 825 | 782 |

| Goods | 511 | 361 | 307 | 320 | 308 | 323 | 354 | 378 | 440 | 594 | 574 |

| Services | 88 | 67 | 53 | 56 | 59 | 61 | 67 | 71 | 124 | 229 | 206 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

348 | 326 | 327 | 341 | 327 | 286 | 289 | 279 | 297 | 324 | 340 |

| Federal | 13 | 16 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 25 | 23 | 22 |

| Territorial | 335 | 310 | 306 | 320 | 307 | 265 | 270 | 259 | 272 | 301 | 317 |

| Addenda: | |||||||||||

| Population (thousands)1 | 59.3 | 57.6 | 55.5 | 53.5 | 52.2 | 51.4 | 51.2 | 51.0 | 50.8 | 50.6 | 50.3 |

| Per capita real GDP (chained dollars) | 18,280 | 16,736 | 14,324 | 15,065 | 14,253 | 14,553 | 14,961 | 15,588 | 16,181 | 20,830 | 26,223 |

- Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Note. Estimates of population for 2013–2017 reflect the incorporation of updated information from the U.S. Census Bureau’s International Data Base.

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | −11.1 | −17.5 | 1.3 | −7.7 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 28.2 | 25.1 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | −1.4 | −15.4 | 3.0 | −3.2 | 2.4 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 5.3 |

| Goods | 1.3 | −17.1 | 5.1 | −3.0 | 7.4 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 9.6 |

| Durable goods | 0.2 | −20.2 | 6.7 | −5.0 | 8.5 | 17.0 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 3.1 | 6.7 |

| Nondurable goods | 2.0 | −15.3 | 4.1 | −1.9 | 6.8 | 1.0 | 0.1 | −2.1 | 1.2 | 11.9 |

| Services | −0.3 | −11.9 | 2.0 | −9.1 | 10.4 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 11.6 | 67.4 | 23.9 |

| Net foreign travel | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Private fixed investment | 2.1 | 4.4 | −8.9 | −6.9 | 5.6 | 9.4 | 42.2 | 62.6 | 65.7 | −8.9 |

| Net exports of goods and services | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Exports | −36.3 | −34.4 | 2.4 | −11.1 | 17.1 | 7.2 | 4.5 | 11.3 | 73.8 | 27.6 |

| Goods | −65.2 | −83.4 | −16.7 | −20.8 | −8.6 | 6.9 | −11.7 | −9.0 | 48.2 | 16.5 |

| Services | 3.4 | −12.5 | 3.8 | −10.5 | 18.5 | 7.3 | 5.2 | 11.9 | 74.5 | 27.8 |

| Imports | −28.6 | −16.0 | 4.5 | −2.5 | 4.8 | 9.5 | 6.7 | 25.4 | 46.6 | −5.3 |

| Goods | −29.3 | −15.0 | 4.3 | −3.8 | 5.0 | 9.6 | 6.6 | 16.4 | 35.0 | −3.3 |

| Services | −24.3 | −21.2 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 3.8 | 8.8 | 7.3 | 73.4 | 85.3 | −10.1 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

−6.4 | 0.2 | 4.4 | −4.0 | −12.8 | 1.1 | −3.2 | 6.3 | 9.2 | 4.7 |

| Federal | 19.2 | 30.7 | 4.4 | −3.6 | −2.5 | −6.4 | 7.4 | 26.3 | −9.5 | −3.3 |

| Territorial | −7.4 | −1.3 | 4.4 | −4.0 | −13.5 | 1.7 | −4.0 | 4.8 | 10.9 | 5.4 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent change: | ||||||||||

| Gross domestic product | −11.1 | −17.5 | 1.3 | −7.7 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 28.2 | 25.1 |

| Percentage points: | ||||||||||

| Personal consumption expenditures | −0.68 | −8.36 | 1.65 | −1.80 | 1.47 | 3.27 | 2.63 | 2.00 | 2.07 | 2.34 |

| Goods | 0.48 | −7.20 | 2.14 | −1.39 | 3.69 | 3.55 | 2.13 | 1.37 | 0.95 | 3.56 |

| Durable goods | 0.03 | −3.14 | 1.02 | −0.84 | 1.52 | 3.22 | 2.09 | 1.99 | 0.63 | 1.11 |

| Nondurable goods | 0.45 | −4.06 | 1.12 | −0.55 | 2.17 | 0.33 | 0.04 | −0.63 | 0.31 | 2.46 |

| Services | −0.13 | −5.45 | 0.99 | −4.67 | 5.37 | 3.25 | 3.13 | 6.64 | 40.08 | 18.42 |

| Net foreign travel | −1.02 | 4.28 | −1.47 | 4.25 | −7.60 | −3.52 | −2.64 | −6.00 | −38.96 | −19.64 |

| Private fixed investment | 0.17 | 0.38 | −0.96 | −0.67 | 0.56 | 0.98 | 4.59 | 8.83 | 13.64 | −2.32 |

| Net exports of goods and services | −8.43 | −9.64 | −1.19 | −3.46 | 4.44 | −2.35 | −2.05 | −9.70 | 9.18 | 23.68 |

| Exports | −25.55 | −17.22 | 0.95 | −4.80 | 7.39 | 3.66 | 2.38 | 5.85 | 39.63 | 19.89 |

| Goods | −26.56 | −12.91 | −0.49 | −0.53 | −0.20 | 0.14 | −0.25 | −0.15 | 0.66 | 0.25 |

| Services | 1.01 | −4.31 | 1.44 | −4.27 | 7.58 | 3.52 | 2.63 | 6.00 | 38.97 | 19.63 |

| Imports | 17.13 | 7.58 | −2.14 | 1.35 | −2.95 | −6.01 | −4.43 | −15.55 | −30.45 | 3.79 |

| Goods | 15.13 | 6.08 | −1.74 | 1.78 | −2.62 | −5.21 | −3.73 | −8.49 | −17.55 | 1.66 |

| Services | 2.00 | 1.50 | −0.41 | −0.43 | −0.33 | −0.80 | −0.70 | −7.06 | −12.89 | 2.13 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

−2.12 | 0.08 | 1.82 | −1.75 | −5.92 | 0.45 | −1.28 | 2.28 | 3.26 | 1.42 |

| Federal | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.11 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.18 | 0.19 | 0.68 | −0.29 | −0.07 |

| Territorial | −2.36 | −0.43 | 1.71 | −1.65 | −5.84 | 0.63 | −1.47 | 1.60 | 3.55 | 1.48 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 12.5 | 2.7 | −0.8 | −0.7 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 4.1 | 6.5 | 4.8 | 1.9 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 6.3 | 1.1 | −0.4 | 5.3 | 1.6 | −0.1 | 1.1 | −2.2 | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 938 | 939 | 795 | 799 | 733 | 751 | 782 | 845 | 931 | 1,250 |

| Private industries | 717 | 727 | 586 | 589 | 540 | 563 | 583 | 642 | 716 | 1,024 |

| Manufacturing | 174 | 50 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 18 | 22 |

| Distributive services | 140 | 165 | 135 | 149 | 153 | 157 | 170 | 178 | 187 | 196 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 111 | 122 | 105 | 110 | 97 | 114 | 134 | 149 | 188 | 450 |

| All other | 291 | 390 | 328 | 314 | 274 | 280 | 269 | 301 | 323 | 355 |

| Government | 222 | 212 | 209 | 210 | 193 | 188 | 198 | 203 | 215 | 226 |

| Federal | 13 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 16 |

| Territorial | 209 | 197 | 193 | 196 | 178 | 173 | 184 | 189 | 199 | 210 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 1,084 | 964 | 795 | 806 | 744 | 748 | 766 | 795 | 822 | 1,054 |

| Private industries | 846 | 745 | 586 | 601 | 560 | 573 | 585 | 616 | 639 | 864 |

| Manufacturing | 181 | 52 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 16 | 20 |

| Distributive services | 147 | 169 | 135 | 147 | 148 | 148 | 158 | 164 | 170 | 179 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 120 | 128 | 105 | 110 | 98 | 110 | 126 | 136 | 165 | 364 |

| All other | 391 | 396 | 328 | 328 | 298 | 303 | 288 | 298 | 283 | 289 |

| Government | 237 | 219 | 209 | 204 | 184 | 176 | 182 | 182 | 185 | 192 |

| Federal | 13 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 |

| Territorial | 224 | 205 | 193 | 191 | 170 | 163 | 168 | 169 | 172 | 178 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | −11.1 | −17.5 | 1.3 | −7.7 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 28.2 |

| Private industries | −12.0 | −21.3 | 2.6 | −6.9 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 35.3 |

| Manufacturing | −71.4 | −65.4 | −10.5 | −7.8 | −27.3 | −6.5 | 32.3 | 21.1 | 23.1 |

| Distributive services | 15.1 | −20.4 | 9.3 | 0.8 | −0.3 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 5.4 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 6.9 | −17.8 | 4.2 | −11.0 | 13.0 | 13.8 | 8.4 | 20.8 | 121.2 |

| All other | 1.2 | −17.1 | 0.1 | −9.1 | 1.6 | −5.2 | 3.5 | −4.9 | 2.1 |

| Government | −7.5 | −4.6 | −2.3 | −9.9 | −4.3 | 3.1 | −0.1 | 2.0 | 3.7 |

| Federal | 10.0 | 9.9 | −15.1 | 1.5 | −2.4 | −2.1 | −3.8 | 4.7 | 3.9 |

| Territorial | −8.6 | −5.6 | −1.2 | −10.8 | −4.5 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 3.7 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent change: | |||||||||

| Gross domestic product | −11.1 | −17.5 | 1.3 | −7.7 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 28.2 |

| Percentage points: | |||||||||

| Private industries | −9.27 | −16.49 | 1.94 | −5.05 | 1.68 | 1.57 | 3.91 | 2.88 | 27.29 |

| Manufacturing | −12.60 | −3.50 | −0.24 | −0.16 | −0.58 | −0.10 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.44 |

| Distributive services | 2.16 | −3.58 | 1.58 | 0.16 | −0.06 | 1.48 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 1.05 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 0.78 | −2.34 | 0.55 | −1.52 | 1.74 | 2.12 | 1.42 | 3.63 | 25.07 |

| All other | 0.39 | −7.07 | 0.04 | −3.53 | 0.58 | −1.92 | 1.22 | −1.81 | 0.72 |

| Government | −1.71 | −1.04 | −0.61 | −2.65 | −1.13 | 0.79 | −0.03 | 0.49 | 0.84 |

| Federal | 0.13 | 0.15 | −0.32 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Territorial | −1.84 | −1.19 | −0.30 | −2.68 | −1.08 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.77 |

Note. Percentage-point contributions do not sum to the percent change in real gross domestic product because of rounding and differences in source data used to estimate GDP by industry and the expenditures measure of real GDP.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total compensation | 533 | 501 | 455 | 456 | 431 | 415 | 433 | 469 | 497 | 581 |

| Private industries | 336 | 307 | 263 | 264 | 259 | 252 | 267 | 298 | 311 | 383 |

| Manufacturing | 74 | 26 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 15 |

| Distributive services | 62 | 72 | 58 | 62 | 62 | 63 | 67 | 71 | 74 | 78 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 61 | 67 | 58 | 60 | 54 | 64 | 74 | 83 | 104 | 150 |

| All other | 140 | 142 | 137 | 134 | 135 | 119 | 118 | 135 | 121 | 141 |

| Government | 197 | 194 | 192 | 191 | 172 | 163 | 166 | 171 | 186 | 198 |

| Federal | 13 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Territorial | 184 | 180 | 176 | 177 | 158 | 149 | 152 | 158 | 171 | 182 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

Guam

Real GDP increased 0.2 percent in 2017 (table C.1.3).

- The growth in the Guam economy reflected an increase in consumer spending (table C.1.4).

- Consumer spending increased for the seventh consecutive year in 2017, driven by growth in retail trade activity.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 4,375 | 4,621 | 4,781 | 4,895 | 4,928 | 5,199 | 5,336 | 5,538 | 5,710 | 5,793 | 5,859 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 2,536 | 2,753 | 2,813 | 2,816 | 2,905 | 3,153 | 3,146 | 3,194 | 3,181 | 3,256 | 3,380 |

| Goods | 1,414 | 1,512 | 1,448 | 1,462 | 1,564 | 1,765 | 1,709 | 1,717 | 1,664 | 1,704 | 1,782 |

| Durable goods | 518 | 542 | 520 | 523 | 564 | 635 | 616 | 596 | 586 | 607 | 640 |

| Nondurable goods | 897 | 970 | 928 | 939 | 1,001 | 1,130 | 1,093 | 1,120 | 1,078 | 1,097 | 1,142 |

| Services | 2,007 | 2,076 | 2,100 | 2,123 | 2,131 | 2,279 | 2,307 | 2,417 | 2,487 | 2,587 | 2,628 |

| Net foreign travel | −885 | −835 | −735 | −769 | −790 | −892 | −871 | −940 | −969 | −1,036 | −1,030 |

| Private fixed investment | 921 | 1,057 | 1,081 | 1,057 | 1,027 | 1,044 | 1,224 | 1,308 | 1,242 | 1,184 | 1,179 |

| Net exports of goods and services | −1,483 | −1,699 | −1,801 | −1,873 | −2,021 | −2,033 | −2,153 | −2,225 | −1,994 | −1,854 | −1,887 |

| Exports | 1,005 | 973 | 838 | 846 | 928 | 1,004 | 1,053 | 1,058 | 1,048 | 1,123 | 1,128 |

| Goods | 115 | 133 | 98 | 73 | 133 | 107 | 177 | 112 | 73 | 82 | 92 |

| Services | 890 | 840 | 740 | 774 | 795 | 897 | 876 | 946 | 975 | 1,041 | 1,036 |

| Imports | 2,489 | 2,673 | 2,639 | 2,719 | 2,949 | 3,037 | 3,206 | 3,283 | 3,042 | 2,976 | 3,015 |

| Goods | 2,018 | 2,115 | 2,051 | 2,098 | 2,289 | 2,395 | 2,512 | 2,558 | 2,331 | 2,285 | 2,324 |

| Services | 470 | 558 | 588 | 621 | 661 | 642 | 694 | 725 | 711 | 691 | 690 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

2,402 | 2,510 | 2,688 | 2,894 | 3,017 | 3,035 | 3,120 | 3,261 | 3,281 | 3,208 | 3,187 |

| Federal | 1,491 | 1,597 | 1,738 | 1,854 | 1,895 | 1,898 | 1,890 | 1,965 | 2,011 | 1,987 | 1,905 |

| Territorial | 911 | 913 | 950 | 1,039 | 1,121 | 1,138 | 1,230 | 1,296 | 1,270 | 1,221 | 1,282 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 4,685 | 4,766 | 4,781 | 4,881 | 4,887 | 4,986 | 5,077 | 5,165 | 5,194 | 5,207 | 5,217 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 2,725 | 2,794 | 2,813 | 2,782 | 2,823 | 2,925 | 2,929 | 2,949 | 2,971 | 3,018 | 3,078 |

| Goods | 1,507 | 1,520 | 1,448 | 1,477 | 1,551 | 1,686 | 1,650 | 1,648 | 1,628 | 1,671 | 1,717 |

| Durable goods | 553 | 538 | 520 | 529 | 575 | 631 | 628 | 618 | 626 | 639 | 649 |

| Nondurable goods | 954 | 983 | 928 | 948 | 976 | 1,056 | 1,024 | 1,030 | 1,004 | 1,035 | 1,070 |

| Services | 2,154 | 2,121 | 2,100 | 2,068 | 2,040 | 2,084 | 2,112 | 2,189 | 2,247 | 2,316 | 2,322 |

| Net foreign travel | −937 | −849 | −735 | −763 | −766 | −840 | −830 | −887 | −906 | −973 | −963 |

| Private fixed investment | 921 | 1,038 | 1,081 | 1,062 | 1,015 | 1,015 | 1,181 | 1,247 | 1,185 | 1,132 | 1,112 |

| Net exports of goods and services | −1,448 | −1,581 | −1,801 | −1,808 | −1,845 | −1,829 | −1,933 | −1,985 | −1,902 | −1,805 | −1,777 |

| Exports | 1,061 | 977 | 838 | 837 | 892 | 938 | 996 | 992 | 976 | 1,052 | 1,052 |

| Goods | 120 | 124 | 98 | 70 | 118 | 93 | 156 | 99 | 66 | 76 | 85 |

| Services | 942 | 853 | 740 | 767 | 771 | 845 | 835 | 892 | 911 | 978 | 968 |

| Imports | 2,509 | 2,558 | 2,639 | 2,646 | 2,737 | 2,767 | 2,928 | 2,977 | 2,878 | 2,858 | 2,829 |

| Goods | 2,031 | 2,008 | 2,051 | 2,024 | 2,090 | 2,149 | 2,274 | 2,309 | 2,232 | 2,237 | 2,224 |

| Services | 477 | 550 | 588 | 623 | 648 | 616 | 653 | 666 | 644 | 620 | 606 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

2,490 | 2,513 | 2,688 | 2,844 | 2,895 | 2,874 | 2,908 | 2,962 | 2,946 | 2,872 | 2,817 |

| Federal | 1,528 | 1,587 | 1,738 | 1,818 | 1,817 | 1,791 | 1,773 | 1,814 | 1,837 | 1,801 | 1,690 |

| Territorial | 964 | 926 | 950 | 1,025 | 1,078 | 1,083 | 1,135 | 1,148 | 1,111 | 1,074 | 1,127 |

| Addenda: | |||||||||||

| Population (thousands)1 | 158.0 | 158.4 | 158.9 | 159.4 | 159.5 | 159.8 | 160.5 | 161.0 | 161.5 | 162.0 | 162.5 |

| Per capita real GDP (chained dollars) | 29,652 | 30,088 | 30,088 | 30,621 | 30,639 | 31,202 | 31,632 | 32,081 | 32,161 | 32,142 | 32,105 |

- Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 1.7 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 2.5 | 0.7 | −1.1 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| Goods | 0.9 | −4.8 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 8.7 | −2.1 | −0.1 | −1.2 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Durable goods | −2.8 | −3.3 | 1.7 | 8.8 | 9.7 | −0.6 | −1.5 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| Nondurable goods | 3.0 | −5.6 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 8.2 | −3.0 | 0.6 | −2.5 | 3.0 | 3.4 |

| Services | −1.5 | −1.0 | −1.5 | −1.4 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 0.3 |

| Net foreign travel | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Private fixed investment | 12.8 | 4.1 | −1.7 | −4.4 | 0.0 | 16.4 | 5.6 | −5.0 | −4.5 | −1.8 |

| Net exports of goods and services | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Exports | −7.9 | −14.2 | −0.1 | 6.5 | 5.2 | 6.1 | −0.4 | −1.6 | 7.8 | 0.0 |

| Goods | 3.1 | −20.8 | −28.2 | 68.1 | −21.3 | 67.5 | −36.3 | −33.3 | 14.4 | 12.7 |

| Services | −9.4 | −13.3 | 3.7 | 0.4 | 9.6 | −1.2 | 6.8 | 2.1 | 7.3 | −1.0 |

| Imports | 2.0 | 3.1 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 5.8 | 1.7 | −3.3 | −0.7 | −1.0 |

| Goods | −1.1 | 2.2 | −1.3 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 5.8 | 1.5 | −3.3 | 0.2 | −0.6 |

| Services | 15.3 | 6.8 | 5.9 | 4.1 | −5.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 | −3.3 | −3.7 | −2.4 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

0.9 | 6.9 | 5.8 | 1.8 | −0.7 | 1.2 | 1.9 | −0.5 | −2.5 | −1.9 |

| Federal | 3.9 | 9.5 | 4.6 | −0.1 | −1.4 | −1.0 | 2.3 | 1.3 | −2.0 | −6.1 |

| Territorial | −3.9 | 2.6 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 0.5 | 4.8 | 1.2 | −3.3 | −3.3 | 5.0 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent change: | ||||||||||

| Gross domestic product | 1.7 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Percentage points: | ||||||||||

| Personal consumption expenditures | 1.49 | 0.41 | −0.65 | 0.84 | 2.15 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.87 | 1.11 |

| Goods | 0.28 | −1.54 | 0.60 | 1.50 | 2.78 | −0.72 | −0.04 | −0.37 | 0.78 | 0.81 |

| Durable goods | −0.34 | −0.38 | 0.18 | 0.93 | 1.10 | −0.07 | −0.17 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| Nondurable goods | 0.62 | −1.16 | 0.42 | 0.57 | 1.67 | −0.65 | 0.13 | −0.50 | 0.57 | 0.64 |

| Services | −0.71 | −0.44 | −0.68 | −0.59 | 0.92 | 0.59 | 1.57 | 1.16 | 1.34 | 0.12 |

| Net foreign travel | 1.91 | 2.39 | −0.57 | −0.07 | −1.55 | 0.21 | −1.11 | −0.36 | −1.24 | 0.19 |

| Private fixed investment | 2.67 | 0.92 | −0.39 | −0.96 | −0.01 | 3.29 | 1.28 | −1.16 | −0.97 | −0.36 |

| Net exports of goods and services | −2.94 | −4.71 | −0.16 | −0.82 | 0.32 | −2.22 | −1.07 | 1.61 | 1.79 | 0.51 |

| Exports | −1.82 | −2.96 | −0.02 | 1.13 | 0.98 | 1.17 | −0.08 | −0.30 | 1.42 | −0.01 |

| Goods | 0.09 | −0.56 | −0.59 | 1.06 | −0.57 | 1.38 | −1.19 | −0.66 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Services | −1.91 | −2.39 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 1.55 | −0.20 | 1.11 | 0.36 | 1.24 | −0.19 |

| Imports | −1.12 | −1.76 | −0.14 | −1.96 | −0.66 | −3.39 | −0.99 | 1.90 | 0.37 | 0.52 |

| Goods | 0.52 | −0.95 | 0.59 | −1.43 | −1.32 | −2.64 | −0.72 | 1.47 | −0.10 | 0.23 |

| Services | −1.64 | −0.81 | −0.73 | −0.53 | 0.66 | −0.75 | −0.26 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.28 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

0.50 | 3.72 | 3.28 | 1.08 | −0.44 | 0.69 | 1.09 | −0.31 | −1.43 | −1.08 |

| Federal | 1.32 | 3.21 | 1.70 | −0.02 | −0.54 | −0.37 | 0.82 | 0.45 | −0.69 | −2.12 |

| Territorial | −0.82 | 0.51 | 1.58 | 1.10 | 0.10 | 1.06 | 0.28 | −0.76 | −0.74 | 1.04 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 3.8 | 3.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 5.9 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 4.7 | −0.4 | 0.8 | −1.1 | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 4,375 | 4,621 | 4,781 | 4,895 | 4,928 | 5,199 | 5,336 | 5,538 | 5,710 | 5,793 |

| Private industries | 2,654 | 2,827 | 2,872 | 2,875 | 2,847 | 3,117 | 3,202 | 3,316 | 3,396 | 3,500 |

| Construction | 291 | 343 | 360 | 394 | 367 | 398 | 448 | 471 | 452 | 423 |

| Distributive services | 436 | 469 | 464 | 495 | 513 | 551 | 547 | 573 | 600 | 657 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 406 | 422 | 429 | 452 | 462 | 487 | 528 | 602 | 634 | 684 |

| Other private | 1,520 | 1,593 | 1,619 | 1,534 | 1,505 | 1,681 | 1,679 | 1,670 | 1,709 | 1,736 |

| Government | 1,721 | 1,795 | 1,910 | 2,020 | 2,081 | 2,082 | 2,134 | 2,222 | 2,314 | 2,293 |

| Federal | 1,008 | 1,071 | 1,157 | 1,217 | 1,253 | 1,249 | 1,250 | 1,274 | 1,311 | 1,274 |

| Territorial | 713 | 724 | 752 | 802 | 828 | 833 | 884 | 948 | 1,003 | 1,019 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 4,685 | 4,766 | 4,781 | 4,881 | 4,887 | 4,986 | 5,077 | 5,165 | 5,194 | 5,207 |

| Private industries | 2,876 | 2,929 | 2,872 | 2,906 | 2,879 | 2,998 | 3,071 | 3,140 | 3,136 | 3,191 |

| Construction | 304 | 360 | 360 | 402 | 369 | 391 | 431 | 440 | 416 | 384 |

| Distributive services | 470 | 502 | 464 | 488 | 495 | 519 | 506 | 525 | 532 | 584 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 437 | 445 | 429 | 459 | 478 | 491 | 534 | 583 | 602 | 636 |

| Other private | 1,667 | 1,622 | 1,619 | 1,557 | 1,537 | 1,595 | 1,603 | 1,594 | 1,589 | 1,590 |

| Government | 1,809 | 1,837 | 1,910 | 1,974 | 2,006 | 1,988 | 2,006 | 2,025 | 2,058 | 2,018 |

| Federal | 1,033 | 1,070 | 1,157 | 1,185 | 1,199 | 1,181 | 1,179 | 1,184 | 1,198 | 1,156 |

| Territorial | 779 | 769 | 752 | 790 | 807 | 808 | 828 | 841 | 859 | 861 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 1.7 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Private industries | 1.8 | −1.9 | 1.2 | −0.9 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 2.2 | −0.1 | 1.8 |

| Construction | 18.4 | 0.0 | 11.6 | −8.0 | 5.9 | 10.1 | 2.3 | −5.5 | −7.7 |

| Distributive services | 7.0 | −7.7 | 5.3 | 1.4 | 4.8 | −2.5 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 9.7 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 1.9 | −3.6 | 7.1 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 8.6 | 9.3 | 3.3 | 5.6 |

| Other private | −2.7 | −0.2 | −3.8 | −1.3 | 3.8 | 0.5 | −0.5 | −0.3 | 0.0 |

| Government | 1.5 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 1.6 | −0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.6 | −1.9 |

| Federal | 3.6 | 8.2 | 2.3 | 1.2 | −1.5 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 1.2 | −3.6 |

| Territorial | −1.4 | −2.1 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent change: | |||||||||

| Gross domestic product | 1.7 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Percentage points: | |||||||||

| Private industries | 1.11 | −1.19 | 0.72 | −0.54 | 2.39 | 1.47 | 1.34 | −0.08 | 1.05 |

| Construction | 1.20 | 0.00 | 0.86 | −0.65 | 0.44 | 0.78 | 0.19 | −0.47 | −0.61 |

| Distributive services | 0.69 | −0.80 | 0.52 | 0.15 | 0.49 | −0.27 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 1.02 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 0.17 | −0.34 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.80 | 0.93 | 0.35 | 0.63 |

| Other private | −0.94 | −0.06 | −1.29 | −0.41 | 1.19 | 0.15 | −0.17 | −0.10 | 0.01 |

| Government | 0.60 | 1.53 | 1.37 | 0.67 | −0.37 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.64 | −0.78 |

| Federal | 0.83 | 1.86 | 0.58 | 0.30 | −0.38 | −0.03 | 0.10 | 0.27 | −0.82 |

| Territorial | −0.22 | −0.34 | 0.79 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.03 |

Note. Percentage-point contributions do not sum to the percent change in real gross domestic product because of rounding and differences in source data used to estimate GDP by industry and the expenditures measure of real GDP.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total compensation | 2,453 | 2,588 | 2,715 | 2,861 | 2,907 | 2,950 | 3,011 | 3,146 | 3,269 | 3,259 |

| Private industries | 1,224 | 1,299 | 1,348 | 1,407 | 1,397 | 1,446 | 1,478 | 1,558 | 1,622 | 1,655 |

| Construction | 135 | 155 | 171 | 192 | 183 | 186 | 213 | 228 | 214 | 194 |

| Distributive services | 245 | 260 | 255 | 270 | 278 | 298 | 295 | 309 | 333 | 356 |

| Accommodations and amusement | 203 | 212 | 217 | 227 | 231 | 243 | 257 | 273 | 298 | 317 |

| Other private | 641 | 671 | 704 | 718 | 706 | 719 | 713 | 748 | 779 | 788 |

| Government | 1,228 | 1,289 | 1,367 | 1,455 | 1,510 | 1,504 | 1,532 | 1,587 | 1,647 | 1,604 |

| Federal | 647 | 695 | 746 | 802 | 835 | 829 | 827 | 849 | 883 | 844 |

| Territorial | 582 | 594 | 621 | 653 | 676 | 675 | 706 | 738 | 764 | 760 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

U.S. Virgin Islands

Real GDP decreased 1.7 percent in 2017 (table D.1.3).

- The decline in the U.S. Virgin Islands economy primarily reflected decreases in exports of services and consumer spending (table D.1.4).

- Exports of services, which consists primarily of spending by tourists, declined after increasing for 5 consecutive years. Tourism arrivals decreased over 24 percent in 2017; arrivals fell significantly in the months following Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

- Consumer spending decreased, reflecting widespread declines in household purchases of goods and services.

New estimates of GDP by industry and compensation by industry for 2016 were also included in the 2017 GDP news releases for each territory. These estimates, along with GDP for 2017, are presented in detail in the accompanying tables.4

The methods used to derive the estimates of GDP and GDP by industry are summarized in the appendix “Summary of Methodologies.”

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 4,803 | 4,250 | 4,203 | 4,339 | 4,239 | 4,095 | 3,762 | 3,622 | 3,748 | 3,863 | 3,855 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 2,280 | 2,311 | 2,368 | 2,428 | 2,524 | 2,528 | 2,526 | 2,527 | 2,609 | 2,641 | 2,640 |

| Goods | 1,319 | 1,262 | 1,215 | 1,205 | 1,233 | 1,206 | 1,200 | 1,207 | 1,213 | 1,216 | 1,117 |

| Durable goods | 822 | 741 | 688 | 664 | 678 | 666 | 718 | 729 | 718 | 732 | 627 |

| Nondurable goods | 497 | 520 | 527 | 541 | 556 | 540 | 481 | 479 | 495 | 484 | 490 |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages | 258 | 264 | 277 | 288 | 305 | 322 | 319 | 323 | 332 | 321 | 326 |

| Other nondurable goods | 239 | 257 | 250 | 253 | 251 | 219 | 162 | 155 | 163 | 163 | 165 |

| Services | 2,075 | 2,184 | 2,156 | 2,233 | 2,323 | 2,402 | 2,444 | 2,482 | 2,596 | 2,643 | 2,572 |

| Housing and utilities | 587 | 632 | 653 | 655 | 710 | 745 | 788 | 790 | 828 | 825 | 851 |

| Health care | 189 | 216 | 231 | 243 | 268 | 288 | 294 | 290 | 312 | 325 | 306 |

| Food services and accommodations | 515 | 538 | 507 | 542 | 551 | 568 | 585 | 617 | 652 | 670 | 615 |

| Other services | 784 | 797 | 764 | 792 | 793 | 801 | 777 | 785 | 804 | 823 | 800 |

| Net foreign travel | −1,114 | −1,135 | −1,004 | −1,011 | −1,032 | −1,080 | −1,117 | −1,162 | −1,200 | −1,218 | −1,049 |

| Private fixed investment | 529 | 476 | 393 | 380 | 363 | 263 | 274 | 286 | 288 | 289 | 310 |

| Change in private inventories | −540 | 180 | 210 | −267 | 104 | 114 | 149 | −6 | −172 | 582 | 839 |

| Net exports of goods and services | 1,532 | 240 | 123 | 580 | 100 | 163 | −231 | −234 | −12 | −678 | −1,064 |

| Exports | 14,141 | 18,412 | 10,717 | 12,945 | 14,371 | 3,278 | 2,525 | 2,795 | 1,537 | 1,808 | 2,450 |

| Goods | 13,002 | 17,255 | 9,696 | 11,922 | 13,329 | 2,186 | 1,395 | 1,623 | 329 | 582 | 1,393 |

| Services | 1,139 | 1,157 | 1,021 | 1,023 | 1,043 | 1,091 | 1,130 | 1,172 | 1,208 | 1,226 | 1,057 |

| Imports | 12,608 | 18,172 | 10,595 | 12,365 | 14,271 | 3,114 | 2,755 | 3,029 | 1,549 | 2,487 | 3,515 |

| Goods | 12,251 | 17,861 | 10,310 | 12,067 | 13,943 | 2,932 | 2,570 | 2,841 | 1,367 | 2,291 | 3,264 |

| Services | 357 | 311 | 285 | 298 | 329 | 182 | 185 | 188 | 182 | 195 | 251 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

1,002 | 1,043 | 1,110 | 1,219 | 1,148 | 1,027 | 1,044 | 1,049 | 1,036 | 1,029 | 1,131 |

| Federal | 117 | 121 | 136 | 176 | 167 | 162 | 160 | 142 | 151 | 147 | 221 |

| Territorial | 885 | 922 | 974 | 1,043 | 981 | 865 | 884 | 907 | 884 | 882 | 909p |

- (p) Fiscal year 2017 audited financial statements for the central government and various independent agencies were not available in time for incorporation into these estimates. Preliminary estimates of territorial government spending are based on information collected from budget documents and reports on federal grant expenditures, including disaster assistance grants.

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 4,460 | 4,502 | 4,203 | 4,241 | 3,895 | 3,310 | 3,117 | 3,090 | 3,096 | 3,124 | 3,071 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 2,417 | 2,313 | 2,368 | 2,396 | 2,375 | 2,297 | 2,240 | 2,232 | 2,287 | 2,293 | 2,236 |

| Goods | 1,430 | 1,269 | 1,215 | 1,183 | 1,138 | 1,080 | 1,074 | 1,096 | 1,119 | 1,109 | 1,001 |

| Durable goods | 898 | 756 | 688 | 659 | 633 | 613 | 664 | 696 | 702 | 691 | 586 |

| Nondurable goods | 534 | 514 | 527 | 524 | 504 | 467 | 414 | 405 | 421 | 423 | 415 |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages | 277 | 267 | 277 | 287 | 293 | 291 | 279 | 275 | 270 | 264 | 260 |

| Other nondurable goods | 257 | 247 | 250 | 237 | 213 | 180 | 139 | 135 | 158 | 166 | 162 |

| Services | 2,184 | 2,195 | 2,156 | 2,205 | 2,220 | 2,224 | 2,197 | 2,212 | 2,273 | 2,292 | 2,168 |

| Housing and utilities | 646 | 625 | 653 | 647 | 652 | 641 | 639 | 645 | 661 | 662 | 647 |

| Health care | 200 | 222 | 231 | 240 | 262 | 279 | 282 | 277 | 297 | 307 | 287 |

| Food services and accommodations | 530 | 543 | 507 | 535 | 531 | 532 | 537 | 552 | 567 | 578 | 520 |

| Other services | 808 | 805 | 764 | 783 | 775 | 774 | 739 | 737 | 747 | 745 | 712 |

| Net foreign travel | −1,197 | −1,153 | −1,004 | −992 | −982 | −1,005 | −1,031 | −1,076 | −1,106 | −1,110 | −932 |

| Private fixed investment | 540 | 475 | 393 | 379 | 356 | 253 | 261 | 269 | 270 | 270 | 287 |

| Change in private inventories | −435 | 111 | 210 | −207 | 59 | 62 | 82 | −4 | −175 | 687 | 801 |

| Net exports of goods and services | 920 | 498 | 123 | 511 | 67 | −2 | −114 | −20 | 60 | −468 | −592 |

| Exports | 11,731 | 11,903 | 10,717 | 10,278 | 8,559 | 1,849 | 1,547 | 1,825 | 1,174 | 1,417 | 1,786 |

| Goods | 10,538 | 10,738 | 9,696 | 9,277 | 7,617 | 1,170 | 861 | 1,116 | 329 | 647 | 1,365 |

| Services | 1,222 | 1,173 | 1,021 | 1,004 | 992 | 1,015 | 1,042 | 1,085 | 1,113 | 1,118 | 939 |

| Imports | 10,811 | 11,405 | 10,595 | 9,768 | 8,492 | 1,851 | 1,661 | 1,844 | 1,114 | 1,885 | 2,378 |

| Goods | 10,469 | 11,106 | 10,310 | 9,482 | 8,226 | 1,728 | 1,539 | 1,723 | 994 | 1,763 | 2,227 |

| Services | 361 | 297 | 285 | 288 | 273 | 151 | 151 | 149 | 145 | 158 | 195 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

1,048 | 1,057 | 1,110 | 1,168 | 1,098 | 998 | 983 | 956 | 933 | 910 | 977 |

| Federal | 121 | 122 | 136 | 170 | 155 | 150 | 146 | 127 | 134 | 128 | 187 |

| Territorial | 927 | 935 | 974 | 998 | 943 | 848 | 837 | 829 | 800 | 782 | 788p |

| Addenda: | |||||||||||

| Population (thousands)1 | 114.7 | 115.9 | 107.3 | 106.4 | 105.9 | 105.4 | 105.3 | 105.1 | 104.9 | 104.7 | 104.5 |

| Per capita real GDP (chained dollars) | 38,884 | 38,844 | 39,171 | 39,859 | 36,780 | 31,404 | 29,601 | 29,401 | 29,514 | 29,838 | 29,388 |

- BEA estimates based on data from the U.S. Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research and the U.S. Census Bureau.

- (p) Fiscal year 2017 audited financial statements for the central government and various independent agencies were not available in time for incorporation into these estimates. Preliminary estimates of territorial government spending are based on information collected from budget documents and reports on federal grant expenditures, including disaster assistance grants.

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 0.9 | −6.6 | 0.9 | −8.2 | −15.0 | −5.8 | −0.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 | −1.7 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | −4.3 | 2.4 | 1.2 | −0.9 | −3.3 | −2.5 | −0.3 | 2.5 | 0.2 | −2.5 |

| Goods | −11.2 | −4.2 | −2.6 | −3.9 | −5.1 | −0.5 | 2.0 | 2.1 | −0.9 | −9.8 |

| Durable goods | −15.7 | −9.0 | −4.3 | −3.9 | −3.1 | 8.3 | 4.8 | 0.9 | −1.7 | −15.1 |

| Nondurable goods | −3.8 | 2.6 | −0.6 | −3.8 | −7.4 | −11.3 | −2.1 | 4.0 | 0.4 | −1.8 |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages | −3.8 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 1.9 | −0.6 | −4.0 | −1.6 | −1.8 | −2.0 | −1.5 |

| Other nondurable goods | −3.8 | 1.2 | −5.0 | −10.1 | −15.9 | −22.5 | −3.0 | 16.9 | 5.2 | −2.2 |

| Services | 0.5 | −1.8 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.2 | −1.2 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 0.8 | −5.4 |

| Housing and utilities | −3.3 | 4.5 | −1.0 | 0.8 | −1.7 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.0 | −2.2 |

| Health care | 10.9 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 9.1 | 6.4 | 1.2 | −2.0 | 7.4 | 3.5 | −6.5 |

| Food services and accommodations | 2.4 | −6.5 | 5.5 | −0.8 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 1.9 | −10.0 |

| Other services | −0.3 | −5.2 | 2.5 | −1.0 | −0.2 | −4.5 | −0.3 | 1.4 | −0.2 | −4.4 |

| Net foreign travel | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Private fixed investment | −12.1 | −17.4 | −3.5 | −6.1 | −28.8 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 6.1 |

| Change in private inventories | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Net exports of goods and services | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. | …….. |

| Exports | 1.5 | −10.0 | −4.1 | −16.7 | −78.4 | −16.3 | 17.9 | −35.6 | 20.7 | 26.0 |

| Goods | 1.9 | −9.7 | −4.3 | −17.9 | −84.6 | −26.5 | 29.6 | −70.6 | 96.9 | 111.0 |

| Services | −4.0 | −13.0 | −1.6 | −1.3 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 2.6 | 0.5 | −16.0 |

| Imports | 5.5 | −7.1 | −7.8 | −13.1 | −78.2 | −10.2 | 11.0 | −39.6 | 69.2 | 26.1 |

| Goods | 6.1 | −7.2 | −8.0 | −13.2 | −79.0 | −10.9 | 11.9 | −42.3 | 77.4 | 26.3 |

| Services | −17.6 | −4.0 | 0.9 | −5.2 | −44.8 | 0.4 | −1.2 | −2.8 | 8.5 | 23.6 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

0.8 | 5.1 | 5.1 | −5.9 | −9.1 | −1.5 | −2.8 | −2.4 | −2.4 | 7.3 |

| Federal | 1.0 | 11.7 | 24.8 | −8.6 | −3.8 | −2.2 | −13.0 | 5.1 | −4.0 | 45.9 |

| Territorial | 0.8 | 4.2 | 2.4 | −5.5 | −10.1 | −1.4 | −0.9 | −3.5 | −2.2 | 0.8p |

- (p) Fiscal year 2017 audited financial statements for the central government and various independent agencies were not available in time for incorporation into these estimates. Preliminary estimates of territorial government spending are based on information collected from budget documents and reports on federal grant expenditures, including disaster assistance grants.

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent change: | ||||||||||

| Gross domestic product | 0.9 | −6.6 | 0.9 | −8.2 | −15.0 | −5.8 | −0.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 | −1.7 |

| Percentage points: | ||||||||||

| Personal consumption expenditures | −2.28 | 1.26 | 0.68 | −0.48 | −1.80 | −1.58 | −0.23 | 1.72 | 0.16 | −1.70 |

| Goods | −3.45 | −1.22 | −0.76 | −1.06 | −1.36 | −0.16 | 0.65 | 0.69 | −0.27 | −3.08 |

| Durable goods | −3.01 | −1.53 | −0.69 | −0.59 | −0.46 | 1.36 | 0.92 | 0.17 | −0.32 | −2.86 |

| Nondurable goods | −0.44 | 0.31 | −0.07 | −0.47 | −0.91 | −1.51 | −0.27 | 0.52 | 0.05 | −0.22 |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages | −0.23 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.12 | −0.04 | −0.33 | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.13 |

| Other nondurable goods | −0.22 | 0.07 | −0.30 | −0.59 | −0.87 | −1.19 | −0.13 | 0.68 | 0.22 | −0.09 |

| Services | 0.23 | −0.89 | 1.17 | 0.34 | 0.10 | −0.73 | 0.42 | 1.91 | 0.57 | −3.72 |

| Housing and utilities | −0.46 | 0.64 | −0.15 | 0.13 | −0.27 | −0.05 | 0.20 | 0.54 | 0.01 | −0.48 |

| Health care | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.08 | −0.16 | 0.59 | 0.29 | −0.55 |

| Food services and accommodations | 0.28 | −0.80 | 0.66 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.32 | −1.74 |

| Other services | −0.06 | −0.95 | 0.46 | −0.18 | −0.03 | −0.89 | −0.06 | 0.29 | −0.04 | −0.95 |

| Net foreign travel | 0.94 | 3.37 | 0.27 | 0.24 | −0.54 | −0.69 | −1.30 | −0.89 | −0.14 | 5.10 |

| Private fixed investment | −1.44 | −1.89 | −0.32 | −0.52 | −2.25 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.45 |

| Change in private inventories | 17.57 | 2.99 | −11.21 | 8.93 | 0.12 | 0.88 | −3.86 | −5.97 | 20.68 | 2.79 |

| Net exports of goods and services | −13.12 | −10.21 | 10.38 | −14.50 | −8.86 | −4.93 | 3.77 | 5.14 | −19.28 | −5.20 |

| Exports | 5.39 | −34.53 | −11.66 | −55.71 | −246.37 | −12.73 | 11.88 | −24.71 | 8.35 | 12.47 |

| Goods | 6.44 | −31.08 | −11.26 | −55.42 | −246.91 | −13.45 | 10.64 | −25.54 | 8.20 | 17.58 |

| Services | −1.05 | −3.45 | −0.40 | −0.29 | 0.54 | 0.72 | 1.24 | 0.83 | 0.16 | −5.11 |

| Imports | −18.51 | 24.31 | 22.04 | 41.21 | 237.51 | 7.80 | −8.11 | 29.85 | −27.63 | −17.67 |

| Goods | −19.95 | 24.03 | 22.10 | 40.84 | 234.36 | 7.82 | −8.17 | 29.70 | −27.23 | −16.46 |

| Services | 1.44 | 0.28 | −0.06 | 0.37 | 3.15 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.15 | −0.41 | −1.21 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment |

0.19 | 1.22 | 1.37 | −1.60 | −2.23 | −0.38 | −0.79 | −0.69 | −0.67 | 1.95 |

| Federal | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.81 | −0.34 | −0.14 | −0.09 | −0.57 | 0.20 | −0.16 | 1.77 |

| Territorial | 0.17 | 0.89 | 0.56 | −1.26 | −2.09 | −0.30 | −0.22 | −0.89 | −0.51 | 0.18p |

- (p) Fiscal year 2017 audited financial statements for the central government and various independent agencies were not available in time for incorporation into these estimates. Preliminary estimates of territorial government spending are based on information collected from budget documents and reports on federal grant expenditures, including disaster assistance grants.

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | −12.3 | 5.9 | 2.3 | 6.4 | 13.7 | −2.5 | −2.9 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 5.9 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 4.9 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.5p |

- (p) Complete information on the 2017 USVI Consumer Price Index was not available in time for incorporation.

- Second footnote

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 4,803 | 4,250 | 4,203 | 4,339 | 4,239 | 4,095 | 3,762 | 3,622 | 3,748 | 3,863 |

| Private industries | 4,020 | 3,443 | 3,374 | 3,461 | 3,398 | 3,331 | 3,006 | 2,867 | 2,945 | 3,048 |

| Goods-producing industries | 1,487 | 993 | 1,042 | 1,035 | 955 | 824 | 593 | 519 | 513 | 506 |

| Services-producing industries | 2,533 | 2,450 | 2,332 | 2,426 | 2,443 | 2,507 | 2,413 | 2,348 | 2,432 | 2,542 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 449 | 435 | 408 | 413 | 422 | 411 | 402 | 393 | 386 | 381 |

| Accommodation and food services | 405 | 424 | 400 | 428 | 436 | 450 | 463 | 489 | 517 | 531 |

| Other services, except government | 1,678 | 1,591 | 1,524 | 1,585 | 1,585 | 1,646 | 1,547 | 1,466 | 1,530 | 1,630 |

| Government | 783 | 807 | 829 | 878 | 841 | 764 | 757 | 755 | 803 | 815 |

| Federal | 120 | 125 | 130 | 141 | 139 | 139 | 140 | 136 | 145 | 142 |

| Territorial | 663 | 682 | 699 | 738 | 702 | 626 | 617 | 619 | 658 | 673 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 4,460 | 4,502 | 4,203 | 4,241 | 3,895 | 3,310 | 3,117 | 3,090 | 3,096 | 3,124 |

| Private industries | 3,634 | 3,661 | 3,374 | 3,408 | 3,086 | 2,568 | 2,410 | 2,408 | 2,391 | 2,423 |

| Goods-producing industries | 1,012 | 1,138 | 1,042 | 1,019 | 774 | 463 | 335 | 284 | 272 | 266 |

| Services-producing industries | 2,646 | 2,523 | 2,332 | 2,389 | 2,324 | 2,233 | 2,255 | 2,341 | 2,343 | 2,391 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 464 | 442 | 408 | 408 | 410 | 388 | 377 | 365 | 352 | 349 |

| Accommodation and food services | 433 | 452 | 400 | 429 | 437 | 434 | 434 | 446 | 449 | 453 |

| Other services, except government | 1,747 | 1,629 | 1,524 | 1,552 | 1,479 | 1,414 | 1,446 | 1,534 | 1,546 | 1,595 |

| Government | 833 | 841 | 829 | 833 | 808 | 755 | 719 | 690 | 715 | 710 |

| Federal | 127 | 129 | 130 | 135 | 131 | 130 | 130 | 123 | 127 | 123 |

| Territorial | 707 | 712 | 699 | 697 | 677 | 624 | 589 | 567 | 588 | 587 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | 0.9 | −6.6 | 0.9 | −8.2 | −15.0 | −5.8 | −0.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Private industries | 0.8 | −7.9 | 1.0 | −9.5 | −16.8 | −6.2 | −0.1 | −0.7 | 1.3 |

| Goods-producing industries | 12.5 | −8.5 | −2.1 | −24.1 | −40.2 | −27.5 | −15.4 | −4.2 | −2.0 |

| Services-producing industries | −4.6 | −7.6 | 2.4 | −2.7 | −3.9 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | −4.7 | −7.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | −5.3 | −2.9 | −3.2 | −3.5 | −0.8 |

| Accommodation and food services | 4.4 | −11.5 | 7.1 | 2.0 | −0.8 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Other services, except government | −6.8 | −6.4 | 1.8 | −4.7 | −4.4 | 2.3 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 3.2 |

| Government | 0.9 | −1.4 | 0.4 | −3.0 | −6.5 | −4.7 | −4.1 | 3.7 | −0.7 |

| Federal | 1.8 | 0.9 | 4.2 | −3.3 | −0.5 | −0.3 | −5.5 | 3.2 | −2.8 |

| Territorial | 0.7 | −1.8 | −0.3 | −2.9 | −7.7 | −5.7 | −3.8 | 3.8 | −0.3 |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent change: | |||||||||

| Gross domestic product | 0.9 | −6.6 | 0.9 | −8.2 | −15.0 | −5.8 | −0.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Percentage points: | |||||||||

| Private industries | 0.65 | −6.38 | 0.82 | −7.63 | −13.88 | −4.97 | −0.09 | −0.55 | 1.06 |

| Goods-producing industries | 3.27 | −2.08 | −0.53 | −6.13 | −11.76 | −5.55 | −2.51 | −0.60 | −0.28 |

| Services-producing industries | −2.62 | −4.29 | 1.35 | −1.50 | −2.12 | 0.58 | 2.42 | 0.05 | 1.33 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | −0.47 | −0.79 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.49 | −0.30 | −0.34 | −0.38 | −0.09 |

| Accommodation and food services | 0.39 | −1.15 | 0.66 | 0.19 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Other services, except government | −2.54 | −2.36 | 0.66 | −1.71 | −1.56 | 0.88 | 2.41 | 0.32 | 1.31 |

| Government | 0.16 | −0.26 | 0.08 | −0.58 | −1.16 | −0.91 | −0.85 | 0.76 | −0.16 |

| Federal | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.13 | −0.10 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.21 | 0.12 | −0.11 |

| Territorial | 0.11 | −0.28 | −0.05 | −0.48 | −1.15 | −0.90 | −0.64 | 0.64 | −0.05 |

Note. Percentage-point contributions do not sum to the percent change in real gross domestic product because of rounding and differences in source data used to estimate GDP by industry and the expenditures measure of real GDP.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total compensation | 2,139 | 2,185 | 2,114 | 2,245 | 2,198 | 2,042 | 1,880 | 1,881 | 1,920 | 1,969 |

| Private industries | 1,399 | 1,411 | 1,318 | 1,393 | 1,386 | 1,319 | 1,157 | 1,150 | 1,151 | 1,182 |

| Goods-producing industries | 369 | 340 | 309 | 317 | 302 | 275 | 110 | 102 | 109 | 108 |

| Services-producing industries | 1,030 | 1,070 | 1,008 | 1,076 | 1,084 | 1,045 | 1,047 | 1,048 | 1,042 | 1,074 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 201 | 205 | 197 | 198 | 209 | 209 | 236 | 222 | 212 | 206 |

| Accommodation and food services | 208 | 217 | 191 | 204 | 208 | 212 | 214 | 221 | 243 | 247 |

| Other services, except government | 621 | 649 | 620 | 674 | 668 | 624 | 597 | 604 | 588 | 622 |

| Government | 741 | 774 | 797 | 852 | 812 | 722 | 724 | 731 | 769 | 786 |

| Federal | 118 | 123 | 129 | 140 | 138 | 137 | 137 | 133 | 142 | 139 |

| Territorial | 622 | 651 | 668 | 712 | 674 | 585 | 586 | 598 | 627 | 648 |

Note. Detail may not add to total because of rounding.

This project represents an important step toward achieving BEA’s and OIA’s long-term goal: to integrate these territories into the full set of U.S. NIPAs. A primary obstacle to realizing this goal is the lack of coverage of these four territories by most of the major surveys used by BEA to produce estimates of GDP and related economic measures.5 Until the territories are included in these surveys, BEA will continue to depend heavily on the assistance and information provided by each of the territorial governments and on continued support from OIA.

Other future enhancements to the estimates for the four territories (subject to data availability and funding) include developing supplementary measures that are included in the full set of the U.S. NIPAs, such as personal income and personal saving rates.

The methodologies used to estimate GDP and GDP by industry for American Samoa, CNMI, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands are consistent with the methods used to estimate GDP and GDP by industry for the United States (excluding the territories). Information from the Economic Census of Island Areas was used to establish levels of GDP for each territory for 2002, 2007, and 2012; for other years, annual indicator series were developed and used to estimate the components of GDP and of GDP by industry.

Gross domestic product

Consumer spending. Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) consists primarily of purchases of goods and services by households.6 Economic census data on the consumer shares of sales by industry were used to benchmark the estimates of household purchases of most goods and selected services.

Annual growth rates for most goods were derived using data on imports of goods and, where available, sales by businesses. For American Samoa, the CNMI, and Guam, data on imports of goods were provided by the territorial government.7 For the U.S. Virgin Islands, data on imports of goods were available from the Census Bureau’s U.S. Trade with Puerto Rico and U.S. Possessions (FT895) and U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services (FT900).8

Estimates that were not benchmarked to economic census data included housing services, utilities services, and financial services, which were estimated independently. Housing services were estimated using information on the number of occupied housing units and average rental rates reported in the Census of Population and Housing. Utilities services were estimated using revenue data reported by government-owned utilities and by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Other services not covered by the economic census—such as financial services furnished without payment, insurance, and sales by government—were estimated using data from private trade sources and government financial reports.

Private investment. Private investment consists of spending on new fixed assets—equipment, software, and structures by private businesses—and improvements to existing assets. It also includes the construction of new residential structures and the improvements to these structures.9 Economic census data on businesses’ capital expenditures on fixed assets were used to benchmark the estimates of private fixed investment for each territory. Annual growth rates were derived using building permit data, construction industry receipts and wages, and imports of capital goods.

Net exports of goods and services. The estimates of exports of goods to the United States from the four territories reflected data from the Census Bureau’s U.S. Trade with Puerto Rico and U.S. Possessions (FT895). Estimates of exports of goods from American Samoa, the CNMI, and Guam to the rest of the world were based on information compiled by the territorial governments. Estimates of exports of goods from the U.S. Virgin Islands to the rest of the world were based on data from the Census Bureau’s U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services (FT900).

Estimates of imports of goods for American Samoa and the CNMI were based on values or quantities of imported commodities reported by the territorial governments. For the U.S. Virgin Islands, estimates of imports of goods reflected data from the FT895 and FT900. For Guam, data on imports of goods are limited, particularly after 2015; the available data were supplemented with other information reported by the Guam government, including sales by businesses.

Information on imports of services and on exports of services other than tourism was limited. Estimates of exports of tourism services for American Samoa were based on visitor arrival data provided by the territorial government and the Federal Aviation Authority. Estimates of exports of tourism services for the CNMI and Guam were based on survey data on tourist expenditures and visitor arrivals provided by the territorial government visitors’ authorities. For the CNMI, these data were supplemented with casino gambling revenues reported in company financial statements. For the U.S. Virgin Islands, the estimate of exports of tourism services was based on expenditures of cruise ship passengers available from the Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association, total visitor expenditures provided by the Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research, U.S. Virgin Islands visitor exit survey data, and gross business revenue data for select industries.

Government consumption expenditures and gross investment. The estimates of government expenditures were prepared for the territorial government sector and for the federal government sector. The primary sources of information for the territorial government estimates were financial statements of the primary government and of the government component units.10 The primary data sources for the federal government estimates were the Census Bureau’s Consolidated Federal Funds Report and the Federal Procurement Data System.11 Information on military pay was provided by the U.S. Department of Defense.

Estimates of real GDP. Inflation-adjusted estimates of total GDP and its components were derived within a chain-type Fisher index framework.12 For most of the detailed components of GDP, inflation-adjusted estimates were calculated by deflating each component using an appropriate price index. Consumer price indexes produced by each territorial government were used to deflate most of the detailed components of PCE. Inflation-adjusted estimates for most components other than PCE were calculated using U.S. prices from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

GDP by industry

Current-dollar estimates. The estimates of GDP by industry were prepared for broad industry groups using a methodology that was developed to incorporate data from the Economic Census of Island Areas. Current-dollar value added for most private industries was extrapolated using indicators such as gross business revenues and compensation. For select private industries, data were available to separately extrapolate gross output and intermediate inputs. These industries included the manufacturing sector in American Samoa and the CNMI and the goods-producing sector in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Current-dollar value added for the government sector was prepared for the territorial government sector and the federal government sector; the primary sources of information were the data sources identified in “Government consumption expenditures and gross investment.”

Real estimates. Inflation-adjusted estimates of GDP by industry were derived within a chain-type Fisher index framework. For most industry sectors, the statistics on chained-dollar value added were prepared using the single-deflation method. Under this method, current-dollar value added of an industry is divided by a gross output price index.13 For industries for which data were available to separately estimate gross output and intermediate inputs, a double-deflation method was used. Under the double-deflation method, current-dollar gross output and current-dollar intermediate inputs are deflated separately, and real value added is computed as the difference between real gross output and real intermediate inputs. Price indexes and other value and quantity data produced by each territorial government, in addition to U.S. prices, were used in the deflation of value added, gross output, and intermediate inputs.

Compensation of employees. Information on payroll and fringe benefits from the economic census was used to benchmark the estimates of compensation by industry. For American Samoa, the CNMI, and Guam, annual growth rates were based on payroll data from a number of sources, including wage information from the Census Bureau’s County Business Patterns and administrative and survey-based wage data provided by the territorial governments. For the U.S. Virgin Islands, wage information from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages was used.

Aya Hamano of BEA and Wali Osman of OIA oversaw the preparation of the territorial economic accounts for American Samoa, the CNMI, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

From BEA, Christina D. Hovland-Battikha and Amy K. Filipek prepared the estimates for all four territories. Brian C. Moyer, Director of BEA, provided overall supervision. Other significant contributors from BEA were Benjamin Kavanaugh and Andrew J. Pinard.

The Economy-Wide Statistics Division of the U.S. Census Bureau provided data from the Economic Census of Island Areas.

From the U.S. Department of the Interior, Nikolao Pula, Director of OIA, provided support throughout the project. Lydia Faleafine-Nomura of OIA served as liaison between BEA and the American Samoa government.

BEA would also like to thank the governor’s offices of the four territories for their contributions. Governor Lolo M. Moliga and Lieutenant Governor Lemanu P. Mauga of American Samoa; Governor Ralph D.L.G. Torres, Lieutenant Governor Arnold I. Palacios, and former Lieutenant Governor Victor B. Hocog of the CNMI; Governor Lou Leon Guerrero, Lieutenant Governor Joshua F. Tenorio, former Governor Eddie B. Calvo, and former Lieutenant Governor Ray S. Tenorio of Guam; and Governor Albert Bryan, Jr., Lieutenant Governor Tregenza A. Roach, former Governor Kenneth E. Mapp, and former Lieutenant Governor Osbert E. Potter of the U.S. Virgin Islands contributed guidance and support throughout the project.

Other key contributors from each territory are listed below.

American Samoa: Keniseli F. Lafaele, Director, Department of Commerce (DOC); Uili Leauanae, Deputy Director, DOC; Meleisea Vai Filiga, Chief Statistician, DOC; Mine Timoteo, Assistant Chief Statistician, DOC; Alex Zodiacal, Assistant to Administrator/Economic Development Division Manager, DOC; Ueligitone Tonumaipe’a, Treasurer, Department of Treasury; Vaaimamao Poufa, Tax Manager, Tax Office, Department of Treasury; Keith Gebauer, Deputy Director for Customs, Department of Treasury; Catherine Saelua, Director, Budget Office; Puleleiite Tufele Liamatua, Jr., Executive Director, American Samoa Telecommunications Authority; Utu Abe Malae, CEO, American Samoa Power Authority; Faumuina J. Faumuina, CEO, LBJ Medical Center; Rosevonne M. Pato, President, American Samoa Community College; Sione Kava, Petroleum Officer, Office of Petroleum Management.

CNMI: Mark O. Rabauliman, Secretary, DOC; Justin H. Andrew, Director, DOC; Fermin C. Sakisat, Computer Specialist III, DOC; Christopher S. Tenorio, Executive Director, Commonwealth Ports Authority (CPA); Skye L. Aldan, Comptroller, CPA; Christopher Concepcion, Managing Director, Marianas Visitors Authority; Larissa Larson, Secretary, Department of Finance (DOF); Maria White, Disclosure Officer, DOF; Lt. Robert Reyes, Customs Officer, DOF; Andrew Reese, Chief Financial Officer, Northern Marianas College; Glen Muna, Commissioner of Education, Public School System (PSS); George Palican, Finance Director, PSS; Violita Diaz and Michelle A. Camacho, Administrative Assistants, Office of the Public Auditor; Gary Camacho, Executive Director, Commonwealth Utility Corporation (CUC); Corina Magofna, Fiscal/Budget Officer, CUC; Rodolfo Urbano, Chief Accountant, CUC; Esther Muna, CEO, Commonwealth Healthcare Corporation.

Guam: Mark G. Calvo, Chief of Staff, Office of the Governor; Carl V. Dominguez, Director, Bureau of Statistics and Plans; Edward Birn, Director, Department of Administration; John Camacho, Director, Department of Revenue and Taxation; Lester Carlson, Acting Director, Bureau of Budget and Management Research; Jay Rojas, Administrator, Guam Economic Development Authority; Doris F. Brooks, Public Auditor, Office of the Public Auditor; Jon Nathan Denight, General Manager, Guam Visitors Bureau; Shirley A. Mabini, Director, Department of Labor; Gary Hiles, Chief Economist, Department of Labor; Albert Perez, Chief Economist, Bureau of Statistics and Plans.

U.S. Virgin Islands: Bernadette V.M. Melendez, Director, Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research (VIBER); Donnie Dorsett, Senior Policy Analyst, VIBER; Marvin Pickering EA, PHR, Director, Virgin Islands Bureau of Internal Revenue; Tamarah Parson-Smalls, Chief Counsel, Virgin Islands Bureau of Internal Revenue; Joanna Meyers-Rhymer, Deputy Director of Operations, Virgin Islands Bureau of Internal Revenue; Carlene Prosper, Data Base Administrator, Virgin Islands Bureau of Internal Revenue; Nellon Bowry, Director, Virgin Islands Office of Management and Budget; Valdamier Collens, Commissioner, Virgin Islands Department of Finance; Clarina Modeste-Elliott, Assistant Executive Commissioner, Virgin Islands Department of Finance; Laurel Payne, Director of Treasury, Virgin Islands Department of Finance; Gary Halyard, Director of Virgin Islands Bureau of Labor Statistics Department of Labor; Sandra Rey, Senior Research Analyst, Virgin Islands Department of Labor.

- OIA is the federal agency that manages the federal government’s relations with the governments of American Samoa, the CNMI, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. It works with these territories to encourage economic development, transparency of government, financial stability, and accountability.

- BEA released these estimates between August and December of 2018. Individual news releases for each of the territories are available on BEA’s website.

- In this article, “consumer spending” refers to “personal consumption expenditures,” “inventory investment” refers to “change in private inventories,” and “government spending” refers to “government consumption expenditures and gross investment.”

- The industry detail shown for GDP by industry and compensation by industry varies depending on the territory.

- These surveys include merchant wholesale trade and retail trade surveys; the annual capital expenditures survey; value of construction put in place; the service annual survey; the annual survey of manufactures; manufacturers’ shipments, inventories, and orders; and survey of government finances.

- A small portion of PCE consists of expenses of nonprofit institutions serving households.

- Data on imports of goods for Guam were limited, particularly after 2015.

- It was assumed that most goods purchased by consumers were imported.

- For American Samoa and the U.S. Virgin Islands, private investment also includes inventory investment.

- Due to delays associated with Hurricanes Irma and Maria, fiscal year 2017 audited financial statements for the U.S. Virgin Islands were not available in time for incorporation into these estimates. Estimates of 2017 spending reflected information collected from budget documents and reports on federal grant expenditures.

- The Consolidated Federal Funds Report was discontinued in 2012 following the publication of the fiscal year 2010 report.

- For additional information, see J. Steven Landefeld, Brent R. Moulton, and Cindy M. Vojtech, “Chained-Dollar Indexes: Issues, Tips on Their Use, and Upcoming Changes,” Survey of Current Business 83 (November 2003):8–17.

- Single deflation approximates the results obtained by double deflation when an industry’s intermediate inputs prices increase at about the same rate as its output prices.