Understanding Asymmetries Between BEA’s and Partner Countries’ Trade Statistics

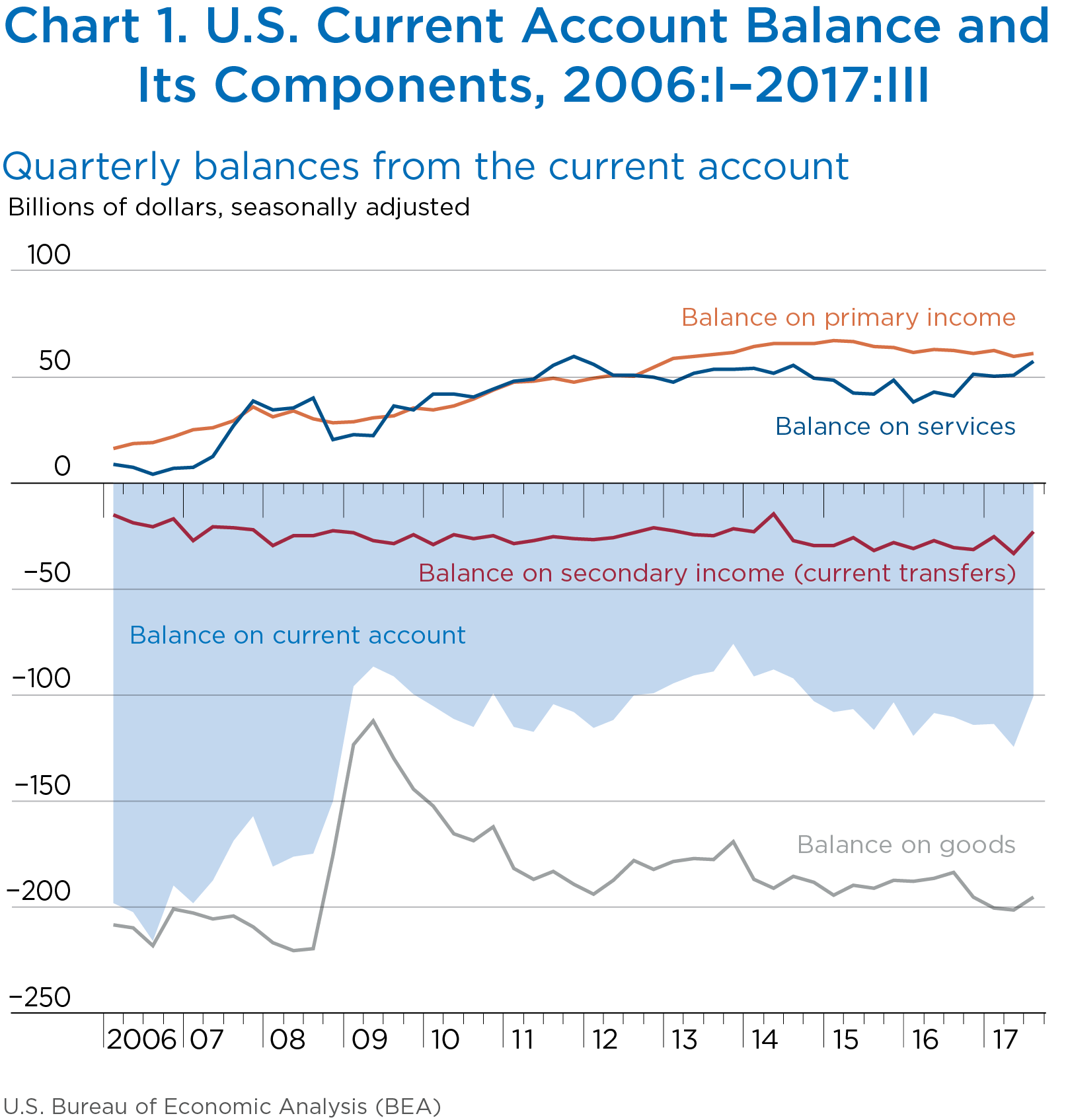

Trade statistics prepared by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provide critical information for understanding the role of the United States in the global economy. BEA releases several data products that include information on U.S. trade in goods and services. The international transactions accounts (ITAs) are a quarterly statistical summary of transactions between U.S. residents and nonresidents organized into three major accounts: the current account, the capital account, and the financial account.1 Exports and impsorts of goods and services are recorded in the current account along with receipts and payments of primary income and receipts and payments of secondary income (chart 1). The ITAs include partner country detail for trade in goods and services, as well as the other major components of the current account, for 38 countries and areas. To supplement the trade in services statistics in the ITAs, BEA publishes annual statistics in its international services series that provide more detail on trade in services by type of service and by partner country than is provided in the ITAs. In addition, BEA releases a monthly report, “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services,” jointly with the U.S. Census Bureau.2

As economies around the world have become increasingly interconnected, leaders in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors rely on trade statistics to inform their decisions, which often carry far-reaching economic or political consequences. Economic events—such as the rise in globalization, the Great Recession, and ongoing trade negotiations—have underscored the need for timely, accurate, and relevant trade statistics. In keeping with BEA’s long history of providing high quality and detailed trade statistics, BEA has been engaged in a long-term initiative to enhance its trade in services statistics further. In October 2016, BEA expanded the number of countries and areas presented in its international services series from 38 to 94. In the coming years, BEA plans to expand the service type and partner country detail presented in the ITAs and to explore the possibility of offering alternative presentations of services trade, such as by the mode of delivery and by the industry of the transactor. As part of this effort, BEA has also been engaging with statistical compilers in other countries to share ideas on data sources and estimation methods, which could lead to improvements to the statistics.

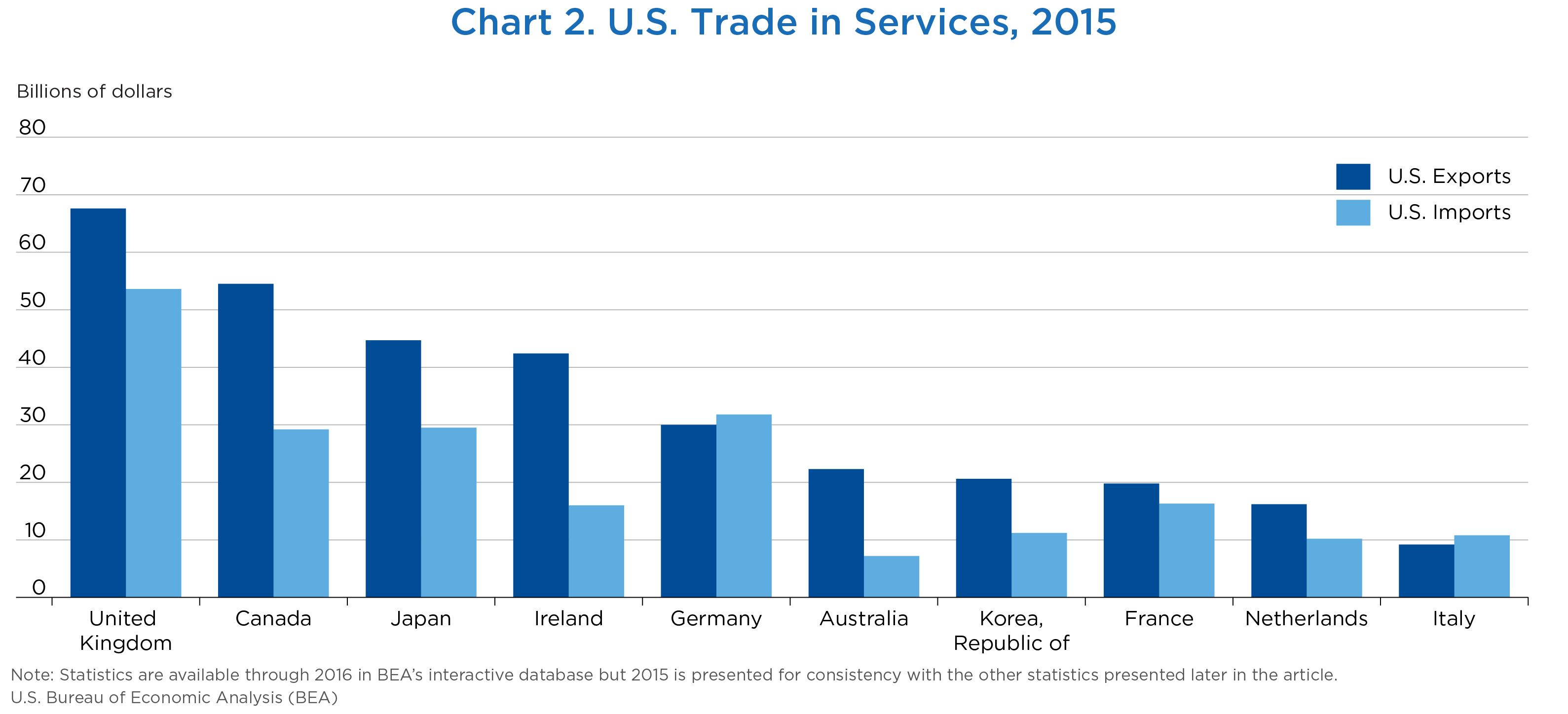

Trade statistics by partner country, or bilateral trade statistics, are important not only for understanding economic interconnections between trading partners but also for developing trade and investment policy and aiding business and government decisionmaking (chart 2). In concept, bilateral trade statistics reported by two partner countries should mirror one another; that is, one country’s exports (imports) should equal the partner country’s imports (exports). In practice, however, differences, or asymmetries, between the data reported by the two countries exist. The persistence of large asymmetries between partner countries’ statistics not only obscures the interpretation of both sets of statistics, but for large economies like the United States and its main trading partners, it also contributes significantly to overall global asymmetries in trade, making it difficult to measure and understand structural changes in the rapidly evolving global economy. Trade statistics published by partner countries differ for several reasons, and it is important for data users to understand why. It is also important to understand that the “true” value for any given statistic could lie between the two countries’ estimates or even outside of that range.

BEA has a long history of analyzing bilateral asymmetries and working with other countries to understand them. For example, BEA has conducted asymmetry reviews and reconciliation exercises with Statistics Canada for decades. This collaboration not only identified and explained asymmetries but also resulted in each country substituting selected statistics produced by the other country in its accounts. Partner country substitution is an option when one country clearly has more accurate and reliable source data for a given data item.

While asymmetries in trade statistics have existed for as long as countries have been compiling them, as Fortanier and Sarrazin (2016) note “increasing complexities in global production arrangements … have increased measurement complexities, and, so, the scope for asymmetries.”3 For many years, international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have monitored these asymmetries. Increasingly, these international organizations have encouraged countries to address persistent bilateral asymmetries by engaging with major trading partners to understand differences in concepts, definitions, and compilation practices.4 The increased emphasis on asymmetries is being driven in part by efforts at the international level to produce trade in value added (TiVA) statistics to inform policy questions about global value chains. An important prerequisite to producing TiVA statistics is a set of bilateral trade statistics without asymmetries. The OECD has been facilitating bilateral meetings between countries to understand and reduce asymmetries. Through this forum, BEA has engaged with statistical compilers from Germany, Ireland, France, and Israel to discuss trade in services statistics. BEA has also been engaged in asymmetry exercises with Canada and Mexico as part of initiatives to develop TiVA statistics for North America and for members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

In this article, we describe how we measure asymmetries and why they exist, describe past asymmetry exercises with partner countries, and take the first step in explaining the asymmetries between the trade in services statistics produced by the United States and the United Kingdom by identifying differences in the definitions and methodologies used in each country. We also quantify, to the extent possible, the contributions of these differences to the asymmetries.

- The ITA news releases, tables, and articles are available on BEA’s Web site. The ITAs are also known as the balance of payments accounts."

- Further information on BEA’s international statistical products are available on BEA’s Web site.

- Fortanier and Sarrazin (2016).

- See for example. “Revisiting Global Asymmetries—Think Globally, Act Bilaterally,” prepared by the IMF Statistics Department for the 28th Meeting of the IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics, 2015.

Measuring Bilateral Asymmetries

Trade analysts use several different measures to evaluate bilateral asymmetries. If we analyze country A’s trade with country B, the export asymmetry measures the difference between country A’s reported exports to country B and country B’s reported imports from country A; that is:

Export Asymmetry(A,B) = Exports(A to B) − Imports(B from A)

Conversely, the import asymmetry measures the difference between country A’s reported imports from country B and country B’s reported exports to country A:

Import Asymmetry(A,B) = Imports(A from B) − Exports(B to A)

The sign of these two asymmetries can be either positive or negative, depending on which country’s statistics for that trade flow are larger. To get a total measure of the asymmetry in trade reported between country A and country B, the absolute asymmetry is used. This is the sum of the absolute values of the export and import asymmetries:

Absolute Asymmetry(A,B) = |Export Asymmetry(A,B)| + |Import Asymmetry(A,B)|

To put the asymmetries in context, bilateral asymmetry ratios for exports and imports can be calculated as follows.5

Exports asymmetry ratio:

(Exports(A to B) − Imports(B from A))/((Exports(A to B) + Imports(B from A))/2)

Imports asymmetry ratio:

(Imports(A from B) − Exports(B to A))/((Imports(A from B) + Exports(B to A))/2)

Asymmetries can arise because of information asymmetries between statistical compilers, and differences in source data and coverage, estimation methods, classification, and time of recording. For trade in services, information asymmetries between the statistical compilers in the two countries can lead to differences in partner country attribution. This applies particularly to statistics collected on business surveys. Compilers may receive conflicting information on their respective surveys of residents. For example, a U.S. exporter may report to BEA that they exported services to the United Kingdom when they actually exported services to a German affiliate of a U.K.-headquartered company. In this scenario, the United States would be over-stating exports to the United Kingdom and understating exports to Germany. Different countries may also experience different levels of compliance with statistical surveys. Protections on the confidentiality of source data, particularly source data from business surveys, often prohibit compilers from sharing data with compilers in the partner country making it difficult to identify causes for asymmetries.

It is also commonly acknowledged that when estimates are based on business surveys, it is typically easier to identify firms that export services than those that import services because exporters of a particular service are likely to be concentrated in relatively large entities in specific industries, whereas importers of services could be individuals or relatively small entities that are spread across many industries. Therefore, it is not surprising that statistics for exports of services estimated from survey data from one country to another often exceed the “mirror” services import statistics from the other country.6

Differences in source data and coverage occur because statistical compilers in each country use their own surveys and administrative data to compile their trade statistics, with differing frequencies and degrees of timeliness. Source data may cover different concepts and reflect different definitions. For example, the geographic definitions used in the source data can differ. As discussed later, BEA’s source data for trade with the United Kingdom include the British Crown Dependencies (the Isle of Man, the Bailiwick of Jersey, and the Bailiwick of Guernsey) as part of the United Kingdom, but the United Kingdom’s source data do not.

Even if statistical compilers had similar source data, they may use different estimation methods, which can lead to statistical differences. For example, compilers may employ different methods for projecting, or estimating, trade when source data are not yet available. These statistical differences are out of scope for the analysis of U.S.-U.K. asymmetries in this article but will be explored in future work.

While international organizations collaborate with countries to develop standard definitions and classifications, differences in classification occur because not all countries adopt the standards at the same pace or to the same degree of completeness. In some cases, source data limitations prevent statistical compilers from fully adopting international standards. For example, BEA’s currently published statistics are based on a version of a survey that did not allow BEA to record transactions related to intellectual property according to the international guidelines. However, BEA recently introduced changes to its surveys, and they now collect the information necessary to record intellectual property transactions according to the international guidelines. BEA is evaluating the new data and plans to incorporate them in the near future.

International guidelines indicate that a service should be recorded at the time the service is provided. However, in practice there are limitations that can cause differences in time of recording. For example, the transactors in each partner country may recognize a transaction on their books at slightly different times, causing the transaction to be reported by each country in different reporting periods. Some countries recognize transactions at the time of payment as a proxy for when the service was provided.

- Wistrom (2004): 8.

- Indeed, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics regularly presents, in its annual reports, asymmetries at the world level, which show that global services exports are consistently higher than global services imports. See, for example, “IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics: Annual Report, 2016.”

Past U.S. Work With Partners: Summary of Main Findings

BEA has worked with statistical compilers in its partner countries to understand asymmetries in bilateral trade statistics in the past. For many years, BEA and Statistics Canada have conducted a reconciliation of their bilateral current account statistics, which include statistics on trade in goods and services. BEA published the results of the most recent reconciliation in 2013.7 As a first step in the reconciliation process, the official U.S. and Canadian statistics were restated to a common basis; that is, they were adjusted for definitional and methodological differences. The framework for restating the statistics to a common basis mainly followed the international guidelines published by the IMF.8 The official U.S. and Canadian statistics largely conformed with the international guidelines, but some differences existed because of data limitations, difficulties in determining country attribution, and differences in classification. Next, adjustments were applied to the statistics of one or both countries to reach reconciled values. For trade in services, the majority of the asymmetries to be reconciled were due to statistical differences, such as the use of different source data. Although the U.S. and Canadian statistics were reconciled as part of this exercise, differences in the official statistics remain. The reconciliation process has identified areas in which each agency can target their data improvement efforts.

In 2006, BEA engaged with the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics (ONS) to analyze asymmetries in trade in services and in primary income statistics. This work was focused on understanding why both countries report trade in services surpluses with one another, a result that continues in the latest statistics.9 Because of legal limitations in the ability to exchange firm-level data and other challenges, BEA and ONS did not fully reconcile the statistics.10 In 2017, BEA and ONS began reengaging to understand these asymmetries. Initial results from this work are presented in this article.

A recent joint paper by BEA and Eurostat presented bilateral trade in services asymmetries for the United States and for all 28 member states of the European Union.11 It found that E.U.-U.S. bilateral asymmetries have shown an increasing trend in recent years.

- Berman, Dozier, and Caron (2013).

- The reconciliation exercise in 2013 mainly followed the Balance of Payments Manual, 5th edition. Since then, the United States and Canada have largely conformed to the newest edition of the guidelines, the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, 6th edition.

- Orford, Dozier, and Lowes (2007).

- For some accounts, the protection of the confidentiality of the source data bars the exchange of detailed data, included firm-level data.

- Howell, Obrzut, and Nowak (2017).

U.S. Asymmetries in Trade in Services Statistics

Table A shows U.S. bilateral trade in services asymmetries with OECD member countries using data for 2015, the most recent year data are available for most OECD countries.12 Given that countries generally capture services exports in their statistics better than services imports, we would expect U.S. exports minus partner imports in column 3 to be positive and U.S. imports minus partner exports in column 6 to be negative. The negative values in column 3 suggest that there could be differences in partner country attribution between U.S. export statistics and the partner country’s import statistics. As expected, many of the largest absolute asymmetries occur with the United States’ largest trading partners.13 The United Kingdom and the United States are each other’s top export destinations for services, and the absolute asymmetry of this trade, $52.0 billion, represents about 70 percent of the U.S. absolute asymmetry with the entire European Union.

Table A also presents asymmetry ratios for the export and import asymmetries. There is perfect symmetry between reported flows (for example, U.S.-reported exports are equal to E.U.-reported imports) when the ratio is equal to zero. The more the ratio diverges from zero, the larger the asymmetry. An export asymmetry ratio of zero for the European Union illustrates that the U.S. export statistics are symmetric to the E.U. mirror imports. However, a review of the asymmetries for the member states of the European Union reveals that this reflects a large positive asymmetry for the United Kingdom that is nearly offset by negative asymmetries for most of the other members of the European Union. This suggests there may be differences in partner country attribution in the statistics reported by the United States and the E.U. member states, where the United States may be recording some transactions with the United Kingdom that should actually be recorded as transactions with another country in the European Union.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. exports | Partner country imports | U.S. export minus partner imports | U.S. imports | Partner country exports | U.S. imports minus partner exports | Total absolute asymmetry | Export asymmetry ratio | Import asymmetry ratio | |

| 2015 | |||||||||

| European Union (28 countries) | 228.4 | 227.9 | 0.5 | 174.1 | 247.8 | −73.7 | 74.3 | 0.00 | −0.35 |

| United Kingdom | 67.6 | 39.3 | 28.2 | 53.6 | 77.4 | −23.8 | 52.0 | 0.53 | −0.36 |

| Netherlands | 16.2 | 31.6 | −15.4 | 10.2 | 18.5 | −8.2 | 23.6 | −0.64 | −0.57 |

| Japan | 44.7 | 54.3 | −9.5 | 29.5 | 40.9 | −11.4 | 20.9 | −0.19 | −0.32 |

| Germany | 30.0 | 38.2 | −8.2 | 31.8 | 43.6 | −11.9 | 20.0 | −0.24 | −0.31 |

| Canada | 54.5 | 56.0 | −1.5 | 29.2 | 45.2 | −16.0 | 17.5 | −0.03 | −0.43 |

| France | 19.8 | 25.0 | −5.3 | 16.3 | 27.3 | −10.9 | 16.2 | −0.24 | −0.50 |

| Australia | 22.3 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 7.2 | 5.9 | 1.3 | 12.3 | 0.65 | 0.20 |

| Korea, Republic of | 20.6 | 28.9 | −8.3 | 11.2 | 14.8 | −3.6 | 11.9 | −0.33 | −0.28 |

| Ireland | 42.4 | 32.7 | 9.7 | 16.0 | 14.8 | 1.3 | 10.9 | 0.26 | 0.08 |

| Luxembourg | 6.6 | 11.3 | −4.7 | 1.8 | 5.5 | −3.7 | 8.4 | −0.53 | −1.02 |

| Belgium | 6.2 | 8.1 | −1.9 | 5.9 | 11.2 | −5.3 | 7.2 | −0.26 | −0.62 |

| Sweden | 6.1 | 8.3 | −2.2 | 3.3 | 7.5 | −4.2 | 6.4 | −0.31 | −0.78 |

| Denmark | 4.3 | 6.4 | −2.1 | 2.7 | 6.9 | −4.2 | 6.3 | −0.40 | −0.88 |

| Italy | 9.2 | 7.7 | 1.5 | 10.8 | 9.7 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 0.18 | 0.10 |

| Spain | 6.8 | 6.3 | 0.5 | 5.8 | 7.1 | −1.3 | 1.8 | 0.07 | −0.20 |

| Hungary | 1.0 | 1.8 | −0.8 | 0.8 | 1.7 | −0.9 | 1.7 | −0.56 | −0.70 |

| Poland | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 2.6 | −0.8 | 1.5 | 0.36 | −0.36 |

| Finland | 1.9 | 2.4 | −0.5 | 2.1 | 2.8 | −0.7 | 1.3 | −0.25 | −0.30 |

| New Zealand | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.47 | 0.07 |

| Greece | 0.9 | 1.1 | −0.2 | 2.8 | 3.2 | −0.5 | 0.6 | −0.16 | −0.16 |

| Russia | 4.7 | 4.9 | −0.2 | 2.4 | 2.8 | −0.4 | 0.6 | −0.04 | −0.16 |

| Lithuania | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.69 | 1.36 |

| Czech Republic | 1.2 | 1.5 | −0.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | −0.2 | 0.5 | −0.20 | −0.19 |

| Austria | 1.6 | 1.7 | −0.1 | 1.6 | 2.0 | −0.4 | 0.4 | −0.03 | −0.20 |

| Slovak Republic | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.79 | −0.46 |

| Slovenia | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.61 | −0.61 |

| Estonia | 0.1 | 0.1 | (*) | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.41 | −0.71 |

| Portugal | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Latvia | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | (*) | 0.1 | 0.83 | −0.16 |

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- *

- Values between zero and +/– $0.5 billion

Notes:

- Column (7) is the sum of the absolute values of columns (3) and (6).

- Column (8) is (BEA-reported U.S. exports – partner country-reported imports)/((BEA-reported U.S. exports + partner country-reported imports)/2).

- Column (9) is (BEA-reported U.S. imports – partner country-reported exports)/((BEA-reported U.S. imports + partner country-reported exports)/2).

Source: OECD. Data extracted January 26, 2018, from OECD.stat.

- Some OECD countries are not included in table A because bilateral trade statistics for those countries are not available.

- For more information on the top markets for services exports and top sources of U.S. services imports, see table C in Allen and Grimm (2017), 4.

Analysis of Trade in Services Asymmetries With the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is both the top destination for U.S. services exports and the top source of U.S. services imports. It is also the country with which the United States has the largest trade in services asymmetries. Furthermore, both countries are reporting a services trade surplus with each other. Since July 2017, BEA has been engaged with the ONS to analyze the asymmetries in the bilateral trade statistics.14 The first round of analysis has been focused on understanding how the differences in how each agency compiles its services trade statistics are contributing to the asymmetries.

Both BEA and ONS use the latest international guidelines as a basis for measuring international trade.15 However, the implementation of the latest international guidelines has moved at different speeds in the two countries. While BEA is still researching and developing methodologies for a few remaining hard-to-measure components, ONS has been able to implement the new guidelines at a faster pace. This has led to a few definitional and methodological differences that contribute to the bilateral asymmetries.

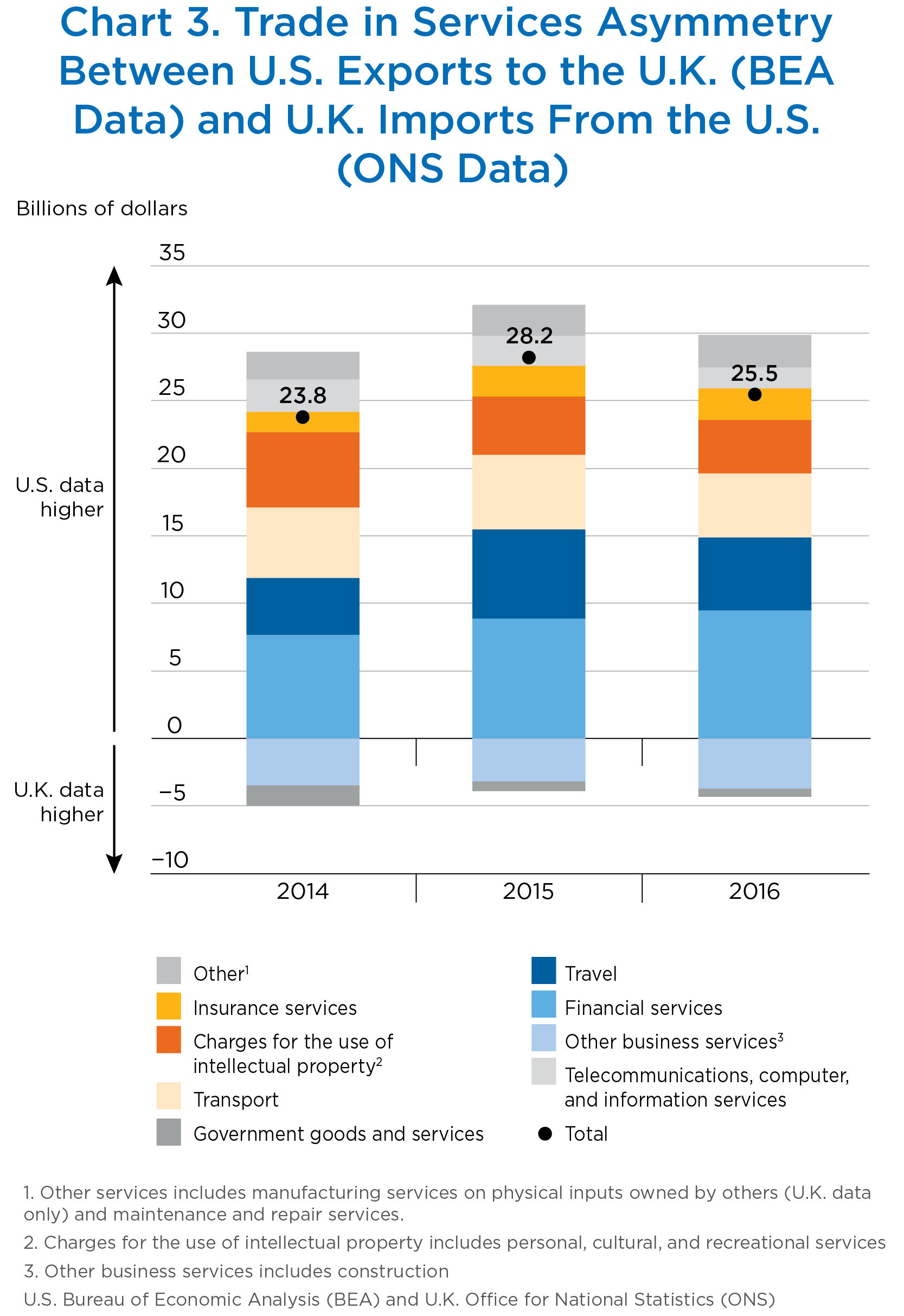

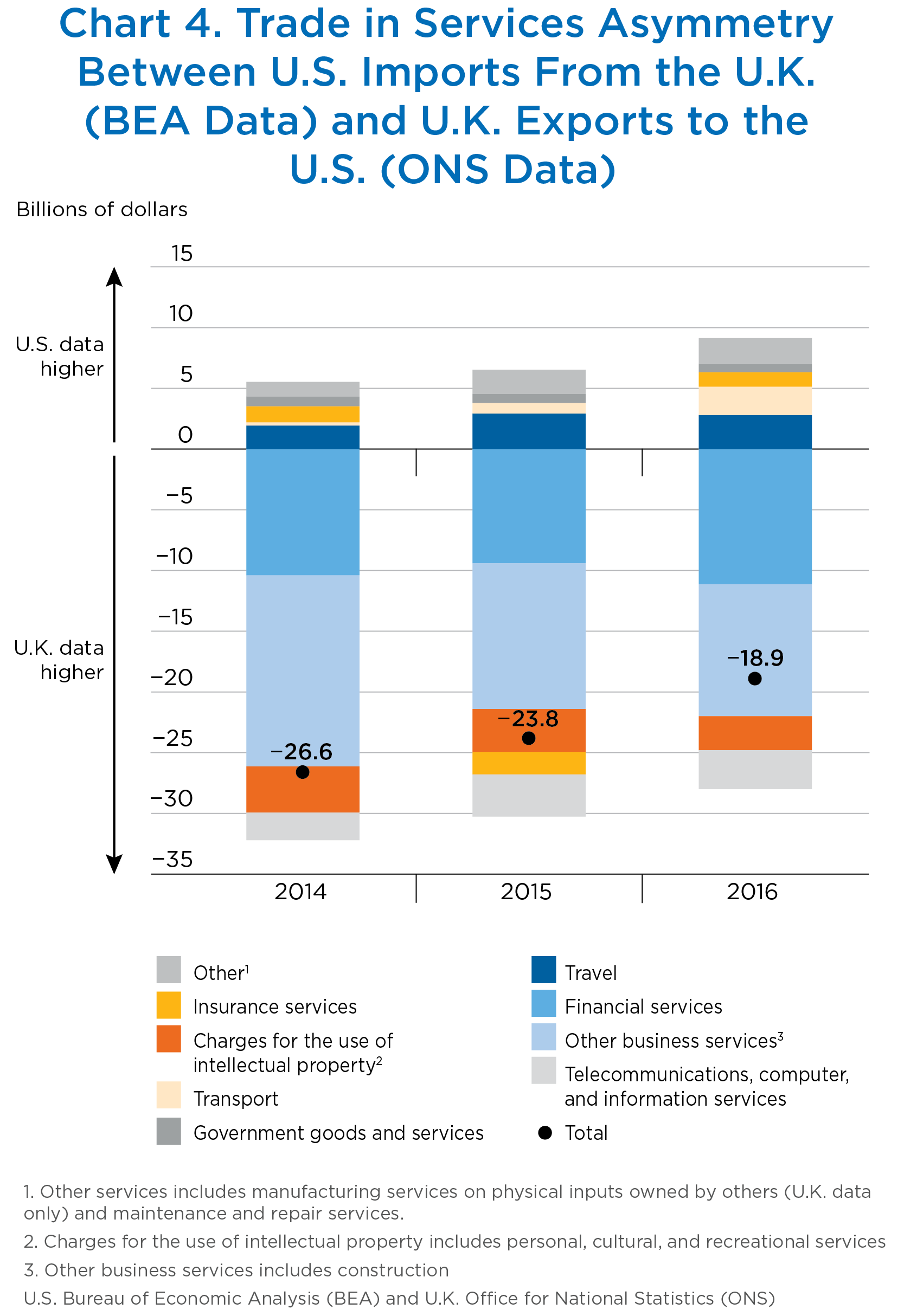

The latest data from BEA and ONS show that the absolute asymmetry in services is $50.4 billion in 2014, $52.0 billion in 2015, and $44.4 billion in 2016. The export and import absolute asymmetries are similar in magnitude. Charts 3 and 4 show how each asymmetry varies over time, how the key service types contribute to the total, and how asymmetries for some service types are partly offsetting. Table B shows the values reported by BEA and ONS as well as the asymmetries calculated from the statistics.

| U.S. exports | U.K. imports | Asymmetry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Services, total | 64.4 | 67.6 | 65.7 | 40.6 | 39.4 | 40.2 | 23.8 | 28.2 | 25.5 |

| Transport | 8.2 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 4.7 |

| Travel | 11.1 | 13.4 | 12.9 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 4.2 | 6.6 | 5.4 |

| Insurance and pension services | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Financial services | 14.5 | 14.1 | 13.9 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 7.7 | 8.9 | 9.5 |

| Charges for the use of intellectual property and personal, cultural, and recreational services | 9.7 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 4.0 |

| Telecommunications, computer, and information services | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| Other business services, including construction | 11.5 | 12.6 | 12.7 | 15.0 | 15.8 | 16.4 | −3.5 | −3.2 | −3.7 |

| Government services n.i.e. | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | −1.5 | −0.7 | −0.6 |

| Other services1 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| U.S. imports | U.K. exports | Asymmetry | |||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Services, total | 52.4 | 53.6 | 51.7 | 79.1 | 77.4 | 70.6 | −26.6 | −23.8 | −18.9 |

| Transport | 7.9 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.3 |

| Travel | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 2.8 |

| Insurance and pension services | 5.0 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 6.4 | 2.9 | 1.3 | −1.9 | 1.2 |

| Financial services | 9.2 | 9.5 | 8.8 | 19.6 | 18.9 | 19.8 | −10.4 | −9.4 | −11.1 |

| Charges for the use of intellectual property and personal, cultural, and recreational services | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 6.4 | −3.8 | −3.5 | −2.8 |

| Telecommunications, computer, and information services | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 5.5 | −2.3 | −3.5 | −3.2 |

| Other business services, including construction | 13.7 | 13.9 | 13.1 | 29.3 | 25.9 | 24.0 | −15.7 | −12.0 | −10.9 |

| Government services n.i.e. | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Other services1 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

- U.K.

- United Kingdom

- Other services includes manufacturing services on physical inputs owned by others (U.K. data only) and maintenance and repair services.

Note. Office for National Statistics (ONS) data converted to U.S. dollars using Bank of England average exchange rate for each year. Asymmetry calculated as BEA data less ONS data.

Sources: BEA and ONS

For the periods shown in this article, each country has consistently reported higher exports than the partner country’s reported imports. For U.S.-reported exports, the absolute asymmetry was $23.8 billion in 2014, $28.2 billion in 2015, and $25.5 billion in 2016 (chart 3). The service categories for which U.S. exports exceed U.K. imports the most are the following: financial services; charges for the use of intellectual property (including personal, cultural, and recreational services for the United Kingdom); travel services; and transport services.16 U.K. imports exceed U.S. exports in “other” business services including construction and government goods and services.17

For U.S.-reported imports, the absolute asymmetry was $26.6 billion in 2014, $23.8 billion in 2015, and $18.9 billion in 2016 (chart 4). The main service categories for which U.S. imports exceed U.K. exports the most are travel services and transport services. U.K. exports exceed U.S. imports in financial services and “other” business services including construction.

The comparison by service type presented in charts 3 and 4 uses the publicly available data, but the discussions between BEA and ONS have begun to identify a number of definitional and methodological differences that are likely contributing to the asymmetries. These definitional and methodological differences should not be seen as comprehensive, but only those that have been identified so far in discussions. In addition, while we were able to identify a number of differences, not all of them could be fully quantified at this point.

Definitional differences can help explain the total services asymmetry as well as the asymmetry for a particular service type. These differences are primarily a result of one country measuring a type of activity in their services trade, while the other country excludes this activity from their services trade and may or may not include it in other accounts. Table C shows the definitional differences that have currently been identified in discussions with ONS and an indicative estimate of the magnitude of each difference, where available.

One notable definitional difference is the inclusion of the British Crown Dependencies in BEA’s trade data while the U.K. ONS trade data exclude transactions of these dependencies. Stemming in part from the engagement with the United Kingdom, BEA will explore the feasibility of modifying its data collection instruments to exclude these dependencies from its geographic definition of the United Kingdom.

| U.S. exports minus U.K. imports (billions of U.S. dollars) | U.S. imports minus U.K. exports (billions of U.S. dollars) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference | Services category it affects | Conceptual basis | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| BEA includes Crown dependencies in definition of U.K., ONS excludes | All | Crown dependencies should be excluded | Quantification is not currently possible | |||||

| Manufacturing services on physical inputs owned by others are included in services trade by ONS and in goods by BEA | Manufacturing services on physical inputs owned by other | Should be included in services | −0.1 | −0.0 | −0.1 | −0.5 | −0.4 | −0.2 |

| Passenger sea transport is included in services trade by ONS, not captured by BEA | Transport | Should be included in services | Quantification is not currently possible at this level of detail | |||||

| Costs of getting goods on board are included in services trade by BEA, excluded by ONS | Transport | Should be excluded | Quantification is not currently possible at this level of detail | |||||

| Construction imports related to work done in the U.S. are included by ONS, not captured by BEA | Construction | Should be included in services | −0.3 | …… | −0.1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Pensions trade is included in services trade by ONS, not captured by BEA | Insurance and pension services | Should be included in services | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… |

| Financial Intermediation Services Indirectly Measured (FISIM) included in services trade by ONS and implicitly included in income in the balance of payments statistics by BEA | Financial services | Should be included in services | −1.3 | −1.4 | −1.3 | −2.8 | −2.5 | −2.6 |

| Net Spread Earnings (NSE) included in services exports by ONS, not captured by BEA | Financial services | Should be included in services | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | −4.4 | −4.3 | −3.9 |

| Outright sales/purchases of franchises and trademarks are included in services trade by BEA and in the capital account by ONS | Charges for the use of intellectual property | Should be included in the capital account | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +0.0 |

| Total of currently identified definitional differences | −1.5 | −1.4 | −1.4 | −7.6 | −7.1 | −6.6 | ||

| Reference | ||||||||

| Total trade in services asymmetry in ONS published figures | 23.8 | 28.2 | 25.5 | −26.6 | −23.8 | −18.9 | ||

- BEA

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- ONS

- Office for National Statistics

- ……

- Indicates that data might be confidential and have therefore been omitted.

- Components may not sum to totals due to rounding.

- n.a.

- Not applicable

Notes:

- The estimates of an activity are given a positive sign when BEA includes the activity, and ONS excludes the activity, in trade in services. The estimates of an activity are given a negative sign when BEA excludes the activity, and the ONS includes the activity, in trade in services. Therefore, the signs are consistent with the total asymmetry shown (BEA data less ONS data). Therefore the sum of each of the differences shows how much of the total asymmetry has been estimated.

- For estimates between $0 and $0.05 billion, a value of +$0.0 billion is shown. For estimates between $0 and –$0.05 billion, a value of –$0.0 billion is shown.

- Net spread earnings is a measurement of service income from trading activities. Estimates shown are calculated using monetary financial institutions data only.

Sources: Office for National Statistics data—consistent with Pink Book 2017 dataset. BEA—U.S. International Services, released on October 24, 2017.

Many of the definitional differences are hard to quantify because the information is often not collected at such a fine level of detail or with specific trading partners. As a result, ONS has used modeling and apportionment to construct many of the estimates shown in table C, so the estimates should be seen as indicative. Estimates may be revised in future work.

Furthermore, the nature of the definitional differences shown in table C mean that the estimates are based only on ONS data and may not represent the true asymmetry if BEA were to measure the activity, as BEA may have a different estimate even when using the same estimation methods. Additionally, if BEA were to measure the activity, the total asymmetry may either increase or decrease, depending on the direction of trade. For example, table C shows an ONS estimate of United Kingdom exports of financial intermediation services indirectly measured (FISIM) to the United States, as BEA currently does not calculate or include FISIM in its services trade statistics.18 If BEA were to calculate FISIM imports from the United Kingdom, it is unlikely that the numbers would match ONS FISIM exports to the United States; there may be an asymmetry. Therefore, it could be misleading to adjust current BEA figures by the current ONS estimate of FISIM exports. In general, if the statistical compiler that does not currently include a particular activity started to estimate the activity, that quantification may well prove different from the data currently available from the other statistical compiler. As such, any adjustment of a country’s figures using another country’s data could give a misleading indication of what would actually be reported if the country were to start measuring this type of activity.

Despite these difficulties, the estimates in table C can be seen as approximate estimates of how much of the total asymmetry each reason may explain. For example, U.K. exports of FISIM to the United States were estimated by ONS to be $2.6 billion in 2016. As FISIM is included in trade in services by the ONS but excluded by BEA, FISIM can explain around $2.6 billion of the total $18.9 billion asymmetry between U.S. services imports from the United Kingdom and the U.K. services exports to the United States. Further, both the United States and the United Kingdom report higher exports than the mirror imports of financial services. Thus, the introduction of FISIM in the U.S. services estimates would help decrease the asymmetry for U.S. financial services imports, but it would increase the asymmetry for U.S. financial services exports. This relationship is true for many of the service types, where solving one definitional difference may decrease the asymmetry in one trade direction, but increase the asymmetry in the other direction.

Together, the definitional differences that have been identified so far and for which quantification has been possible help explain around 30 percent of the total trade in services asymmetry between U.S. imports and U.K. exports in 2014 and 2015 and about 35 percent in 2016. However, the asymmetry between U.S. services exports and U.K. services imports would increase by around 5 percent if the definitional differences for which quantification has been possible were treated consistently by BEA and ONS. Future discussions may identify additional definitional differences, but as emphasized above, these could reduce or increase the asymmetry.

Our current finding that definitional differences only explain a small proportion of the total asymmetry is consistent with previous work on asymmetries between BEA and Statistics Canada. This work found that definitional differences only accounted for a small proportion of the asymmetry between the United States and Canadian trade in services data for 2010 and 2011. The largest source of differences between United States and Canadian trade in services data were statistical differences, reflecting “the use of different source data in the United States and Canada, the difficulty in determining country attribution because of insufficient data, the preliminary nature of some data (particularly for the most recent year), and the use of sample data between benchmark surveys.”19 In future discussions with ONS, we will further compare data sources and methods which may help identify statistical differences for the U.S.-U.K. trade in services asymmetry. However, fully reconciling between data sources may prove difficult given, for example, barriers to sharing confidential firm-level data.

| U.S. exports minus U.K. imports (billions of U.S. dollars) | U.S. imports minus U.K. Exports (billions of U.S. dollars) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Service category where ONS classify component | Service category where BEA classify component | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Personal, cultural and recreational (PCR) services | PCR services. Separately identified. | Within charges for the use of intellectual property and other business services. Not separately identified. | −0.3 | −0.4 | −0.2 | −2.4 | −2.1 | −1.7 |

| Construction services | Construction services. Separately identified. | Within other business services. Separately identified. | −0.3 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.5 | −0.2 | −0.2 |

| Outright sales/purchases of patents | Within research & development services within other business services. Not separately identified. | Within charges for intellectual property. Not separately identified. | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… |

- ……

- Indicates that data might be confidential and have therefore been omitted.

- Components may not sum to totals due to rounding.

Source: Office for National Statistics—data consistent with Pink Book 2017 dataset.

Discussions between BEA and ONS have also begun to identify methodological differences, where both trading partners measure the services activity, but classify them under different service types (table D). These methodological differences will not help explain the trade asymmetry at a total services level, as the component is included somewhere in total services, but they can help explain asymmetries between service types. The presence of methodological differences should be considered by users when comparing data for a particular service type because it may explain part of any asymmetry. For instance, the outright sales and purchases of patents are included in “other” business services by ONS, but they are classified within charges for the use of intellectual property by BEA. This activity should be treated as part of research and development services within “other” business services, according to the international standards. BEA currently includes construction services within “other” business services. Personal, cultural, and recreational services are predominately within BEA estimates of charges for the use of intellectual property, but other elements of personal, cultural, and recreational services are within BEA estimates of “other” business services. To aid the comparison with ONS data, we have grouped the separate ONS estimates for construction and “other” business services together, and similarly we have grouped the separate ONS estimates of charges for the use of intellectual property and personal, cultural, and recreational services together.

- ONS has also published two recent articles on the bilateral asymmetries work. The first, “Asymmetries in Trade Data—A UK Perspective,” was published in July 2017. The second, “Asymmetries in Trade Data—Diving Deeper into UK Bilateral Data,” was published in January 2018.

- Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, 6th Edition Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2009.

- BEA does not report personal, cultural, and recreational services separately; instead, these types of services are predominately within BEA estimates of charges for the use of intellectual property. Therefore, to aid the comparison with ONS data, we have grouped separate ONS estimates of charges for the use of intellectual property and personal, cultural, and recreational services together.

- BEA reports construction services separately, but classifies these services within “other” business services. Therefore, to aid the comparison with ONS data, we have grouped the separate ONS estimates of construction and “other” business services together.

- While BEA does not record FISIM in trade in services, FISIM is included implicitly in income flows in the balance of payments accounts.

- Berman, Dozier, and Caron (2013).

Plans to Enhance BEA’s Trade in Services Statistics

BEA is pursuing several efforts to enhance its trade in services statistics. Continued research into new estimation methodologies, along with several significant changes to BEA’s upcoming benchmark survey of selected services and intellectual property, will allow BEA to further align its trade in services statistics with international guidelines.20 This will also improve comparability between the U.S. statistics and those of its trading partners. However, as alluded to in the earlier discussion of definitional differences, aligning further with international guidelines could reduce some of the asymmetries, but it could also increase asymmetries.

BEA is exploring methods to estimate manufacturing services on physical inputs owned by others and implicitly priced financial services, such as loan and deposit services captured as FISIM. Other changes involve reclassifying currently published transactions to align with international standards. They include the following:

- Reclassifying certain transactions related to intellectual property. Currently, transactions for the use, distribution, and sale of intellectual property are recorded indistinguishably under charges for the use of intellectual property in BEA’s trade in services statistics. BEA has changed its international services surveys to enable it to record these transactions according to the international guidelines. For example, outright sales of the outcomes of research and development, such as the sale of a patent, will be reclassified from charges for the use of intellectual property to research and development services. Identifying outright sales is important to ensure correct accounting of national stocks of research and development assets.

- Introducing a personal, cultural, and recreational services category. BEA does not currently include a category for personal, cultural, and recreational services in its published international trade statistics. Instead, some of these services are commingled in BEA’s statistics under “other” business services and charges for the use of intellectual property. These services include online education or distance learning services, remotely provided telemedicine services, and licenses to use audio-visual and related products such as books, movies, and sound recordings. The recent improvements to BEA’s international services surveys will allow BEA to publish a separate personal, cultural, and recreational services category. BEA also plans to continue exploring alternatives for estimating imports of personal, cultural, and recreational services that are not easily collected on business surveys, such as lottery and gambling services and domestic services.

In addition, BEA plans to further expand the type of service detail published for fast-growing categories such as research and development, intellectual property, and financial services.

- For more information see Allen and Grimm, “U.S. International Services.”

Conclusion and Next Steps

In addition to its ongoing collaboration with ONS to analyze and reduce U.S.-U.K. trade asymmetries, BEA is engaged in similar efforts with Canada, Mexico, and China. BEA began engaging Germany on asymmetries in 2016 and plans to reengage in the near future. BEA also began engaging with France in 2017, with an initial focus on bilateral asymmetries in travel statistics.

Bilateral trade statistics are likely to remain in focus for the foreseeable future. Therefore, continued coordination among statistical compilers is important to understand the dynamics of the asymmetries that exist between the official trade statistics reported by partner countries. It will never be possible to eliminate all asymmetries, but BEA continues to evaluate U.S. trade asymmetries to better understand the causes and to develop approaches to reduce them where possible. We will continue to report our findings through a series of articles on asymmetries in trade and investment data. Bilateral discussions with partner countries could lead to changes in the official statistics of one or both agencies that, in turn, reduce the asymmetries in published statistics.

With colleagues from ONS, BEA will continue to identify and further quantify sources of asymmetries in U.S.-U.K. bilateral statistics. As described above, BEA will also proceed with plans to enhance its statistics on trade in services, including to align more closely with international standards. These enhancements will improve the comparability of our statistics with those of other countries, and thus, provide our users with more clarity about the differences between our statistics and those of our trading partners.

References

Allen, Shari A., and Alexis N. Grimm. 2017. “U.S. International Services: Trade in Services in 2016 and Services Supplied Through Affiliates in 2015.” Survey of Current Business (October): 4.

Berman, Barbara, Edward Dozier, and Denis Caron. 2013. “Reconciliation of the United States-Canadian Current Account, 2010 and 2011.” Survey of Current Business 93 (January).

Fortanier, Fabienne, and Katia Sarrazin. 2016. “Balance International Merchandise Trade Data: Version 1.” Prepared for the OECD Working Party on International Trade in Goods and Services Statistics.

Howell, Kristy, Robert Obrzut, and Olaf Nowak. 2017. “Transatlantic Trade in Services: Investigating Bilateral Asymmetries in EU-U.S. Trade Statistics,” BEA Working Paper 2017–10 (2017).

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2015. “Revisiting Global Asymmetries—Think Globally, Act Bilaterally.” Paper prepared by the IMF Statistics Department for the 28th Meeting of the IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, October 27–29.

Orford,Tom, Edward Dozier, and John Lowes. 2007. “Preliminary Investigations into Asymmetries in Bilateral Trade in Services Between the U.S.A. and the U.K.“ Prepared for the 20th Meeting of the IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics in Washington, DC, October 29–November 1.

United Nations Statistics Division. 2011. International Merchandise Trade Statistics: Concepts and Definitions, 2010 (New York, NY: United Nations).

Wistrom, Bettina. 2004. “International Trade in Services Statistics: Monitoring Progress on Implementation of the Manual and Assessing Data Quality.” Paper presented at Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Eurostat Expert Meeting on Trade-in-Services Statistics in Paris, France, April 19.