The 2022 Annual Update of the National Economic Accounts

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released its annual update of the National Economic Accounts (NEAs), which include the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) and the Industry Economic Accounts (IEAs), on September 29. As part of BEA's ongoing efforts to harmonize the production and publication of the NIPAs, the IEAs, and the Regional Economic Accounts (REAs), improvements incorporated as part of the NEA annual update impacted all three sets of accounts, and each account reflected the same update period. The annual update of the REAs was released on September 30.

This is the first time BEA has produced and published annual updates of the NIPAs, IEAs, and REAs concurrently. In the past, publication of the updated statistics was spread over multiple months beginning with July and ending in October. Following the synchronization of the quarterly NIPA, IEA, and REA statistics introduced in September 2020, coordinating the annual updates for these three major dimensions of gross domestic product (GDP) was an important next step to provide consistency across the accounts and give users a more complete view of the U.S. economy.1

The update of the NEAs covered the first quarter of 2017 through the first quarter of 2022 and resulted in revisions to GDP, GDP by industry, gross domestic income (GDI), and related components. The reference year for index numbers and chained-dollar estimates remains 2012.

The impacts of the annual update on the NIPA and IEA estimates are summarized in the tables and charts provided in this article. Refer to “Information on Updates to the National Economic Accounts” for additional background materials and results. (In particular, the “Summary of Results” tables include detail on quarterly revisions through 2021 and revisions to selected time spans.)

The updated NIPA and IEA estimates reflect the incorporation of newly available and revised source data—the primary driver of this year's revisions—as well as the adoption of improved estimating methods and, for quarterly and monthly measures, the incorporation of updated seasonal adjustment factors.

Major source data

The major source data incorporated into the NIPAs as part of this year's update are summarized in table 1, and additional information on the NIPA components affected by the incorporation of newly available and revised source data is provided in the table “NIPA Revisions: Components Detail and Major Source Data and Conceptual Changes Incorporated, 2017–2021,” available on the “Updates” page on BEA's website. The major source data underlying the GDP by industry estimates are presented in tables C1–C3 of appendix C.

Source data that affected the estimates include the following:

- New U.S. Census Bureau (Census) Service Annual Survey (SAS) data for 2020 and revised SAS data for 2017 through 2019, which replaced previously incorporated SAS data. Most notably, SAS data impacted estimates of consumer spending for services and estimates of private fixed investment in intellectual property products as well as gross output for private services-producing industries.

- Revised Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tabulations of tax returns for corporations and for sole proprietorships for 2019 and new IRS tabulations of tax returns data for 2020 for corporations, sole proprietorships, and partnerships, which affected estimates of corporate profits, proprietors' income, and net interest.

- New Census Annual Survey of Manufactures (ASM) data for 2020 and revised ASM data for 2019, which replaced Census monthly industry shipments and inventories data, and revised monthly industry shipments and inventories data for 2017–2021, all of which impacted estimates of private investment in equipment and inventories as well as gross output for manufacturing industries.

- New Census Annual Retail Trade Survey (ARTS) data for 2020, which replaced Census Monthly Retail Trade Survey (MRTS) data, and revised ARTS data for 2017–2019, both of which impacted estimates of consumer spending for goods and private inventory investment in the NIPAs and estimates of retail trade output in the IEAs.

- Revised U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) data for 2017–2021, which impacted estimates of private and government compensation.

- Revised U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) farm statistics for 2017–2021, which impacted estimates of farm output, inventory investment, and proprietors' income.

- Revised BEA International Transactions Accounts (ITAs) data for 2017–2021, which impacted estimates of exports and imports of goods and services and income flows with the rest of the world.

- Revised Census Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances (GF) data for fiscal years 2017–2019 and newly available GF data for 2020, which impacted estimates of state and local government spending.

| Agency | Data | Years covered and vintage |

|---|---|---|

| Census Bureau | Annual Capital Expenditures Survey | 2019 (revised) |

| 2020 (new) | ||

| Annual Wholesale Trade Survey | 2017-2019 (revised) | |

| 2020 (new) | ||

| Annual Retail Trade Survey | 2017–2019 (revised) | |

| 2020 (new) | ||

| Annual Survey of Manufactures | 2019 (revised) | |

| 2020 (new) | ||

| Monthly indicators of manufactures, merchant wholesale trade, and retail trade | 2017–2021 (revised) | |

| Service Annual Survey | 2017–2019 (revised) | |

| 2020 (new) | ||

| Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances | Fiscal years 2017–2019 (revised) | |

| Fiscal year 2020 (new) | ||

| Value of Construction Put in Place Survey | 2017–2021 (revised) | |

| Quarterly Services Survey | 2017–2021 (revised) | |

| Current Population Survey/Housing Vacancy Survey | 2017–2020 (revised) | |

| 2021 (new) | ||

| Office of Management and Budget | Federal budget | Fiscal year 2021 (revised) |

| Fiscal year 2022 (new) | ||

| Internal Revenue Service | Tabulations of tax returns for corporations and for sole proprietorships | 2019 (revised) |

| 2020 (new) | ||

| Tabulations of tax returns for partnerships | 2020 (new) | |

| Bureau of Labor Statistics | Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages | 2017–2021 (revised) |

| Occupational Employment Statistics program | 2021 (new) | |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm statistics | 2017–2021 (revised) |

| Bureau of Economic Analysis | International Transactions Accounts | 2017–2021 (revised) |

Methodology improvements

The annual update incorporated improvements to estimating methodologies2 and to the presentation of the estimates, including the following:

- BEA improved the supply-use framework to reflect transactions related to ventilator production by auto manufacturers and ventilator purchases by the federal government in 2020 in response to the COVID–19 pandemic. This change resulted in a modification of the composition of gross output for the motor vehicle industry and the composition of government investment in the second and third quarters of 2020 to account for the production and purchase of these ventilators.

- The classification of subsidies introduced as part of the response to the COVID–19 pandemic is improved by distinguishing between “subsidies on products” and “other subsidies on production;” select column and row labels in the supply-use tables (SUTs) have been updated accordingly. This change better aligns BEA's SUTs with international standards and primarily affects gross output valued at basic prices in the supply table and value added at basic prices in the use table.

- BEA improved the deflator for consumer spending and for private fixed investment for used auto and used light truck margin estimates. The consumer price index for used autos and used light trucks replaced the margin producer price index (PPI) for used vehicles sold at new car dealers.

- As with every annual update, the revised estimates incorporate updated quarterly and monthly seasonal factors that capture changes in seasonal patterns that emerge over time. The updated seasonal factors reflect a mix of data that are seasonally adjusted by source agencies as well as data directly adjusted by BEA.

GDP and expenditure components

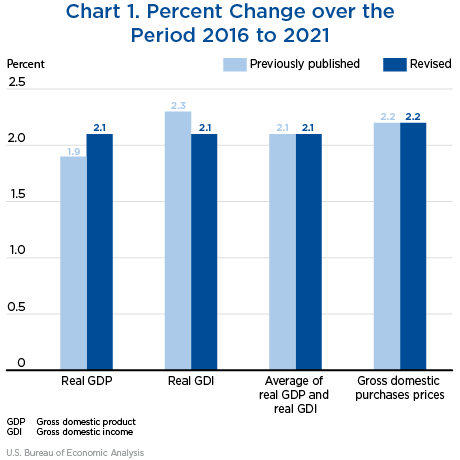

The general picture of economic growth from 2016 to 2021 was unchanged, and updates to the percent change in real GDP and related aggregates were small (table 2A and chart 1). The revisions to real GDP and its components primarily reflect revisions to current-dollar measures; price measures were not significantly revised.

Details on the revisions to the percent change in real GDP are presented in table 2A, and details on the contributions to those revisions are presented in table 2B. Details on revisions, and contributions to revisions, for each expenditure component of real GDP are presented in appendix A (tables A1–A12). As noted above, the major source data incorporated for each component of GDP and GDI are presented in the annual update table “NIPA Revisions: Components Detail and Major Source Data and Conceptual Changes Incorporated, 2017–2021.”

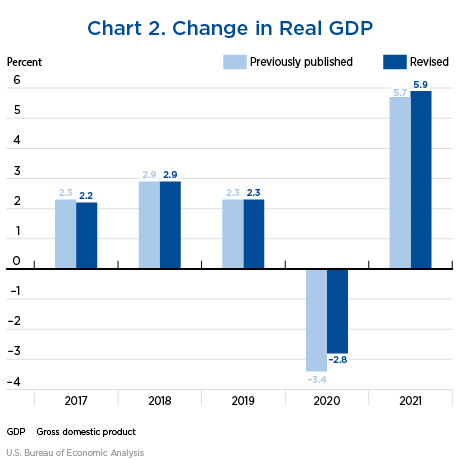

- The downward revision to real GDP growth for 2017 was primarily led by a downward revision to consumer spending on services; a downward revision to state and local government spending also contributed (table 2B and chart 2).3 Within consumer services, the revision was led by spending on financial services, based on revised data from the Federal Reserve Board's (FRB's) Financial Accounts of the United States and by expenditures by nonprofit institutions serving households, based on revised SAS data from Census (appendix table A2). The revision to state and local government was based primarily on revised data from the Census GF survey.

- For 2018, real GDP growth was unrevised, primarily reflecting an upward revision to state and local government spending, based on revised Census GF data, that was offset by an upward revision to imports (a subtraction in the calculation of GDP) based on revised ITA data (table 2B).

- For 2019, real GDP growth was unrevised, reflecting upward revisions to state and local government spending, based on new GF data, and to exports, based on revised ITA data. These upward revisions were offset by downward revisions to consumer spending, led by financial services, based primarily on revised FRB data from the Financial Accounts of the United States, and to nonresidential fixed investment—led by transportation equipment—based on revised ASM data (table 2B and appendix tables A2 and A4).

- The revisions showed a smaller decrease in real GDP for 2020, led by an upward revision to consumer spending on both services and goods (table 2B). Revisions to “other” services, health care, and recreation primarily reflect newly available SAS and revised Quarterly Services Survey (QSS) data, both from Census. Revisions to recreational goods and vehicles as well as furnishings and durable household equipment primarily reflect newly available ARTS data from Census and revised trade source data (appendix table A2).

- The upward revision to real GDP growth for 2021 was led by upward revisions to consumer spending on services, exports of services, and federal government spending that were partly offset by downward revisions to nonresidential fixed investment and state and local government spending (table 2B). Within consumer spending on services, the revision was led by “other” services, based primarily on revised QSS data and revised trade data from BEA's ITAs (appendix table A2). Within exports, the upward revision to services was led by “other business services,” based on revised data from BEA's ITAs (appendix table A8). The downward revision to nonresidential fixed investment was largely due to revisions to equipment, based on revised monthly shipments data from Census' Manufacturers' Shipments, Inventories, and Orders Survey (appendix table A4).

| Line number | Series | Share of current-dollar GDP | Change from preceding period | Revision in percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | Percent (annual rate) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product | 100.0 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 | −2.8 | 5.9 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 68.2 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.0 | −3.0 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 3 | Goods | 23.6 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 12.2 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| 4 | Durable goods | 8.8 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 18.5 | 0.1 | −0.2 | −0.5 | 2.3 | 0.4 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | 14.7 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 8.8 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.4 | −0.3 |

| 6 | Services | 44.6 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.5 | −6.6 | 6.3 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 17.6 | 4.1 | 5.7 | 2.8 | −5.3 | 9.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.6 | 0.2 | −0.8 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 17.7 | 4.1 | 4.9 | 2.5 | −2.3 | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.7 | 0.4 | −0.4 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 13.0 | 4.1 | 6.5 | 3.6 | −4.9 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.7 | 0.4 | −1.0 |

| 10 | Structures | 2.6 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 2.3 | −10.1 | −6.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| 11 | Equipment | 5.1 | 2.8 | 6.6 | 1.3 | −10.5 | 10.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −2.0 | −2.2 | −2.8 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 5.3 | 5.6 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 4.8 | 9.7 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.0 | −0.3 |

| 13 | Residential | 4.8 | 4.0 | −0.6 | −1.0 | 7.2 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | −0.1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 15 | Net exports of goods and services | −3.7 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 16 | Exports | 10.9 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 0.5 | −13.2 | 6.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| 17 | Goods | 7.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 0.1 | −10.1 | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.2 |

| 18 | Services | 3.4 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 1.2 | −18.8 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 4.8 |

| 19 | Imports | 14.6 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 1.1 | −9.0 | 14.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 |

| 20 | Goods | 12.2 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 0.5 | −5.8 | 14.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −0.1 |

| 21 | Services | 2.4 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 4.0 | −22.0 | 12.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| 22 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 17.8 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 0.6 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 23 | Federal | 6.9 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| 24 | National defense | 3.9 | 0.9 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 2.9 | −1.2 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 |

| 25 | Nondefense | 3.0 | −0.3 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 11.2 | 7.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 4.5 |

| 26 | State and local | 10.9 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 3.0 | 0.4 | −0.5 | −0.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | −0.5 | −0.9 |

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 1.1.1 and shares are from NIPA table 1.1.10.

| Line number | Series | Contributions to percent change | Revision in contributions to percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percentage points) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| Percent change at annual rate: | |||||||||||

| 1 | Gross domestic product | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 | −2.8 | 5.9 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Percentage points at annual rates: | |||||||||||

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 1.62 | 1.95 | 1.34 | −2.01 | 5.54 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.14 | 0.54 | 0.27 |

| 3 | Goods | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.66 | 1.07 | 2.72 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| 4 | Durable goods | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.27 | 0.70 | 1.46 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 1.26 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| 6 | Services | 0.80 | 1.12 | 0.69 | −3.08 | 2.83 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.44 | 0.25 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 0.70 | 0.99 | 0.49 | −0.95 | 1.55 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.04 | −0.17 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.44 | −0.40 | 1.30 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.07 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 0.54 | 0.86 | 0.48 | −0.67 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.14 |

| 10 | Structures | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.07 | −0.32 | −0.19 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| 11 | Equipment | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.07 | −0.59 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.17 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.09 | −0.01 |

| 13 | Residential | 0.15 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.05 | −0.55 | 0.24 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.11 |

| 15 | Net exports of goods and services | −0.15 | −0.29 | −0.11 | −0.26 | −1.25 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| 16 | Exports | 0.51 | 0.35 | 0.06 | −1.54 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| 17 | Goods | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.01 | −0.76 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 18 | Services | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.78 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| 19 | Imports | −0.66 | −0.63 | −0.17 | 1.28 | −1.89 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 |

| 20 | Goods | −0.53 | −0.62 | −0.06 | 0.67 | −1.61 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 21 | Services | −0.13 | −0.01 | −0.11 | 0.61 | −0.28 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| 22 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 23 | Federal | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| 24 | National defense | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| 25 | Nondefense | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| 26 | State and local | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.18 | −0.06 | −0.10 |

Note. Contributions are from NIPA table 1.1.2.

Prices

Revisions to BEA's various price measures, such as gross domestic purchases, GDP, and personal consumption expenditures (PCE), were small and reflect revised and newly available source data and, for the most recent year (2021), the regular incorporation of annual weights (tables 3A–3B).

- The percent change in the gross domestic purchases price index—a measure of the prices paid by consumers, businesses, and governments—was unrevised for 2017–2019 and was revised up for 2020–2021.

- The percent change in GDP prices was unrevised for 2017–2020 and was revised up for 2021.

- The percent change in PCE prices was unrevised for 2017–2019, was revised down for 2020, and was revised up for 2021.

| Line number | Series | Change from preceding period | Revision in percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (annual rate) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic purchases | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 |

| 3 | Goods | 0.3 | 0.8 | −0.4 | −0.7 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 |

| 4 | Durable goods | −2.3 | −1.5 | −1.0 | −0.9 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.1 | −0.7 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | 1.6 | 1.9 | −0.1 | −0.7 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| 6 | Services | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.3 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 10 | Structures | 2.5 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 4.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −1.5 |

| 11 | Equipment | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| 13 | Residential | 4.5 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |||||

| 15 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 2.3 | 3.7 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 5.3 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| 16 | Federal | 1.8 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 3.4 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 |

| 17 | National defense | 1.6 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 18 | Nondefense | 2.2 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 3.0 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.5 |

| 19 | State and local | 2.6 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| Addenda | |||||||||||

| 20 | Gross domestic purchases: | ||||||||||

| 21 | Food | −0.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| 22 | Energy goods and services | 8.7 | 8.1 | −2.2 | −8.6 | 20.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| 23 | Excluding food and energy | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 24 | Personal consumption expenditures: | ||||||||||

| 25 | Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | −0.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 26 | Energy goods and services | 8.7 | 8.0 | −2.1 | −8.5 | 20.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| 27 | Excluding food and energy | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.2 |

| 28 | Gross domestic product (GDP) | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 29 | Exports of goods and services | 2.6 | 3.4 | −0.5 | −2.4 | 11.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.3 |

| 30 | Imports of goods and services | 2.2 | 2.7 | −1.6 | −2.2 | 7.4 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Note. Most percent changes are from NIPA table 1.6.7; percent changes for PCE for food and energy goods and services and for PCE excluding food and energy are from NIPA table 2.3.7. GDP, export, and import prices are from NIPA table 1.1.7.

| Line number | Series | Contribution to percent change in prices | Revision in contributions to percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percentage points) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| Percent change at annual rate: | |||||||||||

| 1 | Gross domestic purchases | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Percentage points at annual rates: | |||||||||||

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 1.21 | 1.41 | 0.98 | 0.72 | 2.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.10 |

| 3 | Goods | 0.06 | 0.16 | −0.08 | −0.16 | 1.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.08 |

| 4 | Durable goods | −0.16 | −0.11 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.08 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | 0.23 | 0.27 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 6 | Services | 1.15 | 1.25 | 1.06 | 0.88 | 1.56 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.16 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 10 | Structures | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.03 |

| 11 | Equipment | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| 13 | Residential | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| 15 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 0.40 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| 16 | Federal | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| 17 | National defense | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 18 | Nondefense | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 |

| 19 | State and local | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.70 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.17 |

| Addenda | |||||||||||

| 20 | Gross domestic purchases | ||||||||||

| 21 | Food | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 22 | Energy goods and services | 0.22 | 0.21 | −0.06 | −0.22 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 23 | Excluding food and energy | 1.67 | 2.11 | 1.56 | 1.33 | 3.57 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.29 |

Note. Contributions are from NIPA table 1.6.8.

Income

Revisions to the components of national income and GDI primarily reflect the incorporation of revised IRS Statistics of Income (SOI) data, new and revised QCEW data, revised ITA data, and data from the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury) (table 4).

- The downward revision for 2017 reflects small revisions across several components.

- The downward revision for 2018 primarily reflects a revision to farm proprietors' income based on new USDA Agricultural Resource Management Survey data.

- The upward revision for 2019 primarily reflects upward revisions to financial and nonfinancial corporate profits and to net interest payments, based on revised SOI data for domestic profits and revised ITA data for profits from the rest of the world.

- The upward revision for 2020 was led by a downward revision to subsidies, as pandemic-related tax credits were revised down by over $100 billion, based on data from the Treasury's Office of Tax Analysis on claims filed for tax credits to fund paid sick leave (as part of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act), and Employee Retention Credits (as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act).4 Upward revisions to net interest payments, compensation of employees, and corporate profits also contributed.

- The revision for 2021 reflects downward revisions to several income components including wages and salaries, primarily based on QCEW data; farm proprietors' income, primarily based on data from the USDA Economic Research Service's February Farm Income Forecast; corporate profits, particularly profits received by the rest of the world, based on ITA data; and net interest.

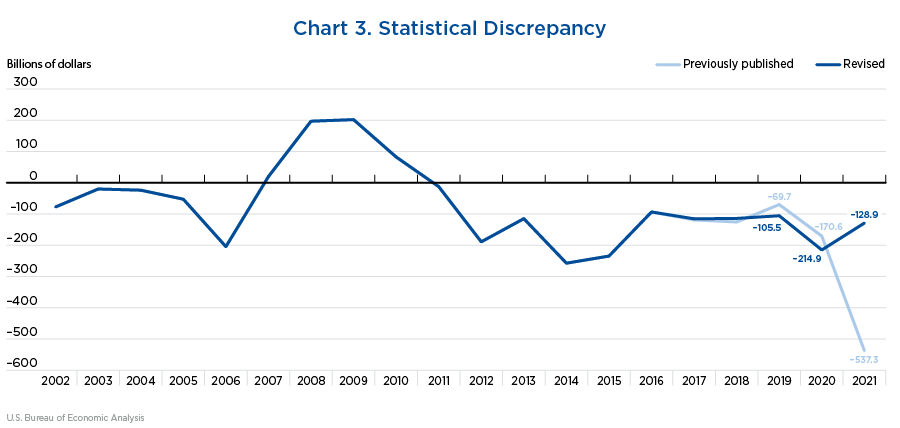

One of the most notable impacts of the annual update is on the statistical discrepancy (table 5 and chart 3). In theory, GDI should equal GDP, but in practice, they differ because their components are estimated using largely independent source data; the statistical discrepancy had increased significantly for 2021 in the previously published estimates. The upward revision to GDP and the downward revision to GDI for 2021 resulted in a sizeable revision to the discrepancy (from −$537.3 billion to −$128.9 billion). With the revision, the statistical discrepancy as a percent of GDP is −0.6 percent; the average, without regard to sign, over the last 20 years, is 0.8 percent.

| Line number | Series | Level | Revision in level | Revision in change | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | National income | 16,766.8 | 17,661.7 | 18,327.9 | 17,894.6 | 19,785.5 | −8.1 | −11.6 | 54.9 | 183.9 | −152.4 | −8.1 | −3.5 | 66.5 | 129 | −336.4 |

| 2 | Compensation of employees | 10,424.4 | 10,957.9 | 11,448.1 | 11,592.7 | 12,538.5 | −1.8 | −1.6 | 0.4 | 20.6 | −60.2 | −1.7 | 0.1 | 2 | 20.2 | −80.8 |

| 3 | Wages and salaries | 8,474.4 | 8,900.0 | 9,324.6 | 9,457.4 | 10,290.1 | −0.3 | −0.5 | 1.1 | 13.3 | −53.7 | −0.2 | −0.2 | 1.6 | 12.2 | −67 |

| 4 | Government | 1,348.2 | 1,402.0 | 1,450.5 | 1,494.5 | 1,544.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0 | 8.7 | 0.2 | 0.4 | −0.3 | −0.3 | 8.8 |

| 5 | Other | 7,126.2 | 7,498.1 | 7,874.1 | 7,962.9 | 8,746.0 | −0.5 | −1.1 | 0.8 | 13.3 | −62.3 | −0.5 | −0.5 | 1.9 | 12.5 | −75.6 |

| 6 | Supplements to wages and salaries | 1,950.0 | 2,057.9 | 2,123.5 | 2,135.4 | 2,248.4 | −1.5 | −1.1 | −0.6 | 7.3 | −6.5 | −1.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 7.9 | −13.8 |

| 7 | Employer contributions for employee pension and insurance funds | 1,345.3 | 1,433.1 | 1,472.9 | 1,476.2 | 1,550.3 | −1.2 | −1.2 | −1.7 | 11.9 | 23.9 | −1.2 | 0 | −0.5 | 13.6 | 12 |

| 8 | Employer contributions for government social insurance | 604.7 | 624.8 | 650.7 | 659.1 | 698.1 | −0.3 | 0 | 1.1 | −4.5 | −30.4 | −0.3 | 0.3 | 1 | −5.6 | −25.8 |

| 9 | Proprietors' income with IVA and CCAdj | 1,504.6 | 1,568.7 | 1,601.4 | 1,643.1 | 1,753.6 | −1.2 | −11.7 | 2.5 | −6.9 | −68.3 | −1.2 | −10.5 | 14.2 | −9.4 | −61.4 |

| 10 | Farm | 39.1 | 29.2 | 29.1 | 45.2 | 51.3 | −0.4 | −9.7 | −9.3 | −25 | −46.4 | −0.4 | −9.4 | 0.5 | −15.7 | −21.4 |

| 11 | Nonfarm | 1,465.5 | 1,539.5 | 1,572.3 | 1,597.9 | 1,702.2 | −0.8 | −2 | 11.8 | 18.1 | −21.9 | −0.9 | −1.1 | 13.8 | 6.2 | −40 |

| 12 | Rental income of persons with CCAdj | 650.6 | 680.0 | 698.2 | 719.8 | 723.8 | −2.1 | −1.9 | 6.1 | 8.3 | −2.6 | −2.2 | 0.2 | 8 | 2.1 | −10.8 |

| 13 | Corporate profits with IVA and CCAdj | 2,128.6 | 2,311.9 | 2,402.2 | 2,260.1 | 2,771.1 | −0.3 | 7 | 34.4 | 16.3 | −34.7 | −0.3 | 7.3 | 27.4 | −18.1 | −51 |

| 14 | Taxes on corporate income | 297.3 | 297.7 | 297.4 | 288.9 | 388.2 | −15 | 16.1 | −4.8 | 13.3 | 7 | −14.9 | 31.1 | −20.9 | 18 | −6.3 |

| 15 | Profits after tax with IVA and CCAdj | 1,831.2 | 2,014.3 | 2,104.7 | 1,971.2 | 2,382.8 | 14.6 | −9.2 | 39.1 | 3.1 | −41.8 | 14.7 | −23.8 | 48.3 | −36 | −44.8 |

| 16 | Net dividends | 1,264.1 | 1,338.4 | 1,531.2 | 1,541.3 | 1,659.3 | 0 | 0 | 144.8 | 146.5 | 240.7 | 0 | 0 | 144.8 | 1.6 | 94.2 |

| 17 | Undistributed profits with IVA and CCAdj | 567.1 | 675.9 | 573.5 | 429.9 | 723.6 | 14.6 | −9.2 | −105.7 | −143.4 | −282.4 | 14.7 | −23.8 | −96.5 | −37.8 | −139 |

| 18 | Net interest and miscellaneous payments | 609.0 | 594.1 | 571.2 | 665.8 | 644.1 | −3.5 | −4.6 | 13 | 47 | −42 | −3.5 | −1.1 | 17.6 | 34 | −89 |

| 19 | Taxes on production and imports | 1,367.4 | 1,461.4 | 1,530.0 | 1,526.3 | 1,663.4 | 1.1 | −0.3 | −2.3 | −8.4 | 22.3 | 1.1 | −1.4 | −2 | −6 | 30.6 |

| 20 | Less: Subsidies | 59.9 | 63.3 | 73.0 | 657.3 | 481.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −104.1 | −11.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −104.1 | 93 |

| 21 | Business current transfer payments (net) | 148.7 | 158.9 | 164.0 | 144.1 | 171.0 | −0.4 | 0.9 | 1.7 | −14.5 | 7 | −0.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | −16.2 | 21.5 |

| 22 | To persons (net) | 48.3 | 50.1 | 55.1 | 44.1 | 71.0 | −0.5 | −0.2 | −0.8 | −15.8 | 4 | −0.5 | 0.3 | −0.6 | −14.9 | 19.8 |

| 23 | To government (net) | 99.7 | 104.8 | 97.5 | 97.5 | 97.4 | 0.1 | 1 | 1.7 | −0.3 | 2.1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 | −2 | 2.4 |

| 24 | To the rest of the world (net) | 0.7 | 4.1 | 11.4 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | −0.7 |

| 25 | Current surplus of government enterprises | −6.5 | −7.9 | −14.2 | −0.1 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | −0.9 | 17.3 | 15 | 0.1 | 0.6 | −1.7 | 18.3 | −2.3 |

- CCADj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment

Note. Dollar levels are from NIPA table 1.12.

| Line number | Series | Level | Revision in level | Revision in change | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product | 19,477.3 | 20,533.1 | 21,381.0 | 21,060.5 | 23,315.1 | −2.3 | 5.9 | 8.4 | 166.7 | 319.0 | −2.3 | 8.2 | 2.5 | 158.3 | 152.3 |

| 2 | Less: Statistical discrepancy | −115.3 | −114.0 | −105.5 | −214.9 | −128.9 | 3.6 | 11.5 | −35.9 | −44.4 | 408.4 | 3.7 | 7.9 | −47.3 | −8.5 | 452.8 |

| 3 | Equals: Gross domestic income | 19,592.6 | 20,647.0 | 21,486.5 | 21,275.4 | 23,444.0 | −5.9 | −5.6 | 44.3 | 211.1 | −89.4 | −5.9 | 0.3 | 49.8 | 166.8 | −300.5 |

| 4 | Plus: Income receipts from the rest of the world | 1,031.1 | 1,138.7 | 1,172.2 | 971.3 | 1,087.0 | −1.6 | −3.5 | 11.9 | −21.6 | −58.0 | −1.6 | −1.8 | 15.3 | −33.5 | −36.4 |

| 5 | Less: Income payments to the rest of the world | 738.2 | 848.4 | 894.2 | 774.3 | 913.9 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 3.7 | 21.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 | −0.2 | 3.5 | 17.6 |

| 6 | Equals: Gross national income | 19,885.6 | 20,937.4 | 21,764.5 | 21,472.4 | 23,617.1 | −7.5 | −9.4 | 55.9 | 185.7 | −168.7 | −7.5 | −1.9 | 65.3 | 129.8 | −354.4 |

| 7 | Less: Consumption of fixed capital | 3,118.7 | 3,275.6 | 3,436.6 | 3,577.8 | 3,831.6 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.9 | −16.3 | 0.6 | 1.6 | −1.1 | 0.9 | −18.2 |

| 8 | Equals: National income | 16,766.8 | 17,661.7 | 18,327.9 | 17,894.6 | 19,785.5 | −8.1 | −11.6 | 54.9 | 183.9 | −152.4 | −8.1 | −3.5 | 66.5 | 129.0 | −336.4 |

| 9 | Less: | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | Corporate profits with IVA and CCAdj | 2,128.6 | 2,311.9 | 2,402.2 | 2,260.1 | 2,771.1 | −0.3 | 7.0 | 34.4 | 16.3 | −34.7 | −0.3 | 7.3 | 27.4 | −18.1 | −51.0 |

| 11 | Taxes on production and imports less subsidies | 1,307.6 | 1,398.1 | 1,457.1 | 869.0 | 1,181.5 | 1.1 | −0.3 | −2.3 | 95.8 | 33.4 | 1.1 | −1.5 | −2.0 | 98.1 | −62.4 |

| 12 | Contributions for government social insurance, domestic | 1,298.9 | 1,361.6 | 1,424.6 | 1,450.0 | 1,540.8 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 3.2 | −9.5 | −52.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | −12.6 | −43.1 |

| 13 | Net interest and miscellaneous payments on assets | 609.0 | 594.1 | 571.2 | 665.8 | 644.1 | −3.5 | −4.6 | 13.0 | 47.0 | −42.0 | −3.5 | −1.1 | 17.6 | 34.0 | −89.0 |

| 14 | Business current transfer payments (net) | 148.7 | 158.9 | 164.0 | 144.1 | 171.0 | −0.4 | 0.9 | 1.7 | −14.5 | 7.0 | −0.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | −16.2 | 21.5 |

| 15 | Current surplus of government enterprises | −6.5 | −7.9 | −14.2 | −0.1 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | −0.9 | 17.3 | 15.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | −1.7 | 18.3 | −2.3 |

| 16 | Plus: Personal income receipts on assets | 2,703.5 | 2,862.2 | 3,119.0 | 3,095.4 | 3,202.4 | −4.4 | −6.1 | 151.0 | 183.3 | 261.1 | −4.4 | −1.7 | 157.1 | 32.3 | 77.8 |

| 17 | Plus: Personal current transfer receipts | 2,855.7 | 2,976.6 | 3,144.8 | 4,231.2 | 4,617.3 | −0.7 | 0.3 | 5.7 | −10.0 | 19.5 | −0.6 | 0.9 | 5.4 | −15.7 | 29.5 |

| 18 | Equals: Personal income | 16,839.8 | 17,683.8 | 18,587.0 | 19,832.3 | 21,294.8 | −10.4 | −22.2 | 162.6 | 204.7 | 202.1 | −10.4 | −11.8 | 184.8 | 42.1 | −2.7 |

- CCADj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment

- Beginning in 1986, repairs and alterations of equipment are reclassified from goods to services.

- Includes net exports of goods under merchanting, beginning in 1999, reclassified from services to goods.

- Includes maintenance and repair services, insurance services, financial services, telecommunication, computer and information services, personal, cultural, and recreational services, construction services, and other other business services.

Note. Dollar levels are from NIPA table 1.7.5.

Measures of personal income were also impacted by newly available and revised SOI data (table 6):

- Personal income was revised down for 2017, as most components—particularly personal interest income—were revised down.

- For 2018, the downward revision to personal income was led by a downward revision to farm proprietors' income, based on revised USDA data.

- For 2019–2021, the revisions were due primarily to upward revisions to personal dividend income, based on revised IRS SOI data for 2019, newly available SOI data for 2020, and more complete annual company financial reports and newly available Quarterly Financial Report data from Census for 2021.

- The personal saving rate (personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income) was unrevised for 2017–2018, was revised up for 2019–2020, and was revised down for 2021. For 2019, there was an upward revision to personal income and a downward revision to personal outlays. For 2020, the upward revision to income more than offset upward revisions to personal outlays and personal current taxes. For 2021, upward revisions to outlays and taxes more than offset the upward revision to income.

| Line number | Series | Level | Revision in level | Revision in change | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Personal income | 16,839.8 | 17,683.8 | 18,587.0 | 19,832.3 | 21,294.8 | −10.4 | −22.2 | 162.6 | 204.7 | 202.1 | −10.4 | −11.8 | 184.8 | 42.1 | −2.7 |

| 2 | Compensation of employees | 10,424.4 | 10,957.9 | 11,448.1 | 11,592.7 | 12,538.5 | −1.8 | −1.6 | 0.4 | 20.6 | −60.2 | −1.7 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 20.2 | −80.8 |

| 3 | Wages and salaries | 8,474.4 | 8,900.0 | 9,324.6 | 9,457.4 | 10,290.1 | −0.3 | −0.5 | 1.1 | 13.3 | −53.7 | −0.2 | −0.2 | 1.6 | 12.2 | −67.0 |

| 4 | Private industries | 7,126.2 | 7,498.1 | 7,874.1 | 7,962.9 | 8,746.0 | −0.5 | −1.1 | 0.8 | 13.3 | −62.3 | −0.5 | −0.5 | 1.9 | 12.5 | −75.6 |

| 5 | Government | 1,348.2 | 1,402.0 | 1,450.5 | 1,494.5 | 1,544.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 8.7 | 0.2 | 0.4 | −0.3 | −0.3 | 8.8 |

| 6 | Supplements to wages and salaries | 1,950.0 | 2,057.9 | 2,123.5 | 2,135.4 | 2,248.4 | −1.5 | −1.1 | −0.6 | 7.3 | −6.5 | −1.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 7.9 | −13.8 |

| 7 | Proprietors' income with IVA and CCAdj | 1,504.6 | 1,568.7 | 1,601.4 | 1,643.1 | 1,753.6 | −1.2 | −11.7 | 2.5 | −6.9 | −68.3 | −1.2 | −10.5 | 14.2 | −9.4 | −61.4 |

| 8 | Farm | 39.1 | 29.2 | 29.1 | 45.2 | 51.3 | −0.4 | −9.7 | −9.3 | −25.0 | −46.4 | −0.4 | −9.4 | 0.5 | −15.7 | −21.4 |

| 9 | Nonfarm | 1,465.5 | 1,539.5 | 1,572.3 | 1,597.9 | 1,702.2 | −0.8 | −2.0 | 11.8 | 18.1 | −21.9 | −0.9 | −1.1 | 13.8 | 6.2 | −40.0 |

| 10 | Rental income of persons with CCAdj | 650.6 | 680.0 | 698.2 | 719.8 | 723.8 | −2.1 | −1.9 | 6.1 | 8.3 | −2.6 | −2.2 | 0.2 | 8.0 | 2.1 | −10.8 |

| 11 | Personal income receipts on assets | 2,703.5 | 2,862.2 | 3,119.0 | 3,095.4 | 3,202.4 | −4.4 | −6.1 | 151.0 | 183.3 | 261.1 | −4.4 | −1.7 | 157.1 | 32.3 | 77.8 |

| 12 | Personal interest income | 1,549.0 | 1,608.9 | 1,658.1 | 1,647.3 | 1,658.6 | −4.5 | −6.1 | 6.1 | 33.0 | 17.9 | −4.4 | −1.7 | 12.3 | 26.9 | −15.1 |

| 13 | Personal dividend income | 1,154.6 | 1,253.4 | 1,460.9 | 1,448.1 | 1,543.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 144.9 | 150.3 | 243.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 144.8 | 5.4 | 92.9 |

| 14 | Personal current transfer receipts | 2,855.7 | 2,976.6 | 3,144.8 | 4,231.2 | 4,617.3 | −0.7 | 0.3 | 5.7 | −10.0 | 19.5 | −0.6 | 0.9 | 5.4 | −15.7 | 29.5 |

| 15 | Government social benefits to persons | 2,807.4 | 2,926.5 | 3,089.7 | 4,187.1 | 4,546.4 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 15.5 | −0.1 | 0.6 | 6.2 | −0.7 | 9.7 |

| 16 | Other current transfer receipts, from business (net) | 48.3 | 50.1 | 55.1 | 44.1 | 71.0 | −0.5 | −0.2 | −0.8 | −15.8 | 4.0 | −0.5 | 0.3 | −0.6 | −14.9 | 19.8 |

| 17 | Less: Contributions for government social insurance | 1,298.9 | 1,361.6 | 1,424.6 | 1,450.0 | 1,540.8 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 3.2 | −9.5 | −52.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | −12.6 | −43.1 |

| 18 | Less: Personal current taxes | 2,048.6 | 2,074.9 | 2,198.4 | 2,236.4 | 2,661.7 | −0.4 | −1.4 | −6.7 | 40.8 | 76.5 | −0.4 | −1.0 | −5.3 | 47.6 | 35.7 |

| 19 | Equals: Disposable personal income (DPI) | 14,791.2 | 15,608.9 | 16,388.6 | 17,595.9 | 18,633.1 | −10.0 | −20.8 | 169.3 | 163.9 | 125.5 | −10.0 | −10.8 | 190.1 | −5.5 | −38.4 |

| 20 | Less: Personal outlays | 13,717.5 | 14,428.6 | 14,942.0 | 14,603.6 | 16,389.8 | −7.3 | −10.2 | −39.5 | 59.1 | 163.4 | −7.4 | −2.9 | −29.3 | 98.6 | 104.4 |

| 21 | Equals: Personal saving | 1,073.8 | 1,180.3 | 1,446.6 | 2,992.3 | 2,243.4 | −2.7 | −10.6 | 208.8 | 104.8 | −37.9 | −2.7 | −8.0 | 219.5 | −104.0 | −142.8 |

| 22 | Personal saving as a percentage of DPI (percent) | 7.3 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 17.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.4 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | −0.8 | −0.7 |

- CCADj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment

Note. Dollar levels are from NIPA table 2.1.

GDP and GDI

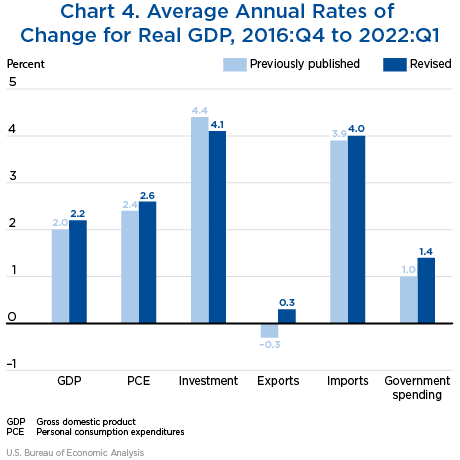

From the fourth quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2022, real GDP was revised up 0.2 percentage point, from an increase of 2.0 percent to an increase of 2.2 percent (chart 4). Real GDI over the same period was revised down, from 2.6 percent to 2.3 percent, and the average of GDP and GDI was revised from 2.3 percent to 2.2 percent.

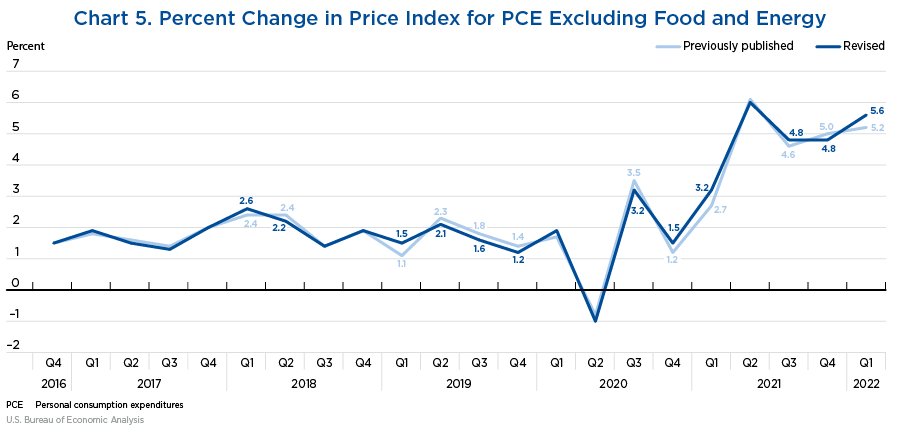

Prices

From the fourth quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2022, the average annual rate of increase in the price index for gross domestic purchases was 2.6 percent, revised up 0.1 percentage point from the previously published estimates. From the fourth quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2022, the average annual rate of increase in the price index for PCE was 2.7 percent, revised up 0.1 percentage point. The increase in the “core” PCE price index, which excludes food and energy, was 2.4 percent, the same as previously published. Quarterly revisions in the index primarily reflect updated BLS consumer price indexes as well as BEA's improved deflator for used motor vehicles (chart 5).

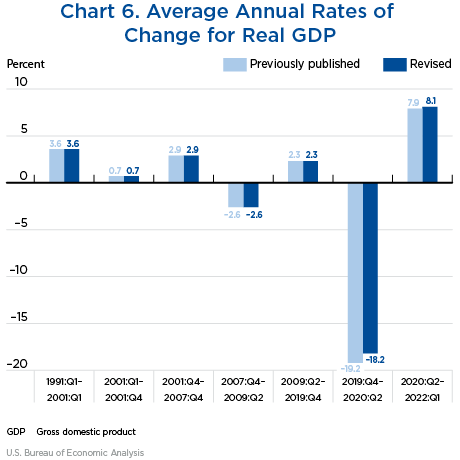

Business cycles

For the period of expansion from the second quarter of 2009 to the fourth quarter of 2019, real GDP increased at an average annual rate of 2.3 percent, unrevised from the previously published estimate (chart 6). The rate of growth in real GDI over the period was revised up from 2.4 percent to 2.5 percent. The percent change in real GDP during the pandemic-related recession from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2020 was revised up, decreasing 18.2 percent, compared with 19.2 percent in the previously published estimates. The recovery from the second quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021 was stronger than previously estimated, at 8.1 percent, rather than 7.9 percent.

GDP and expenditure components

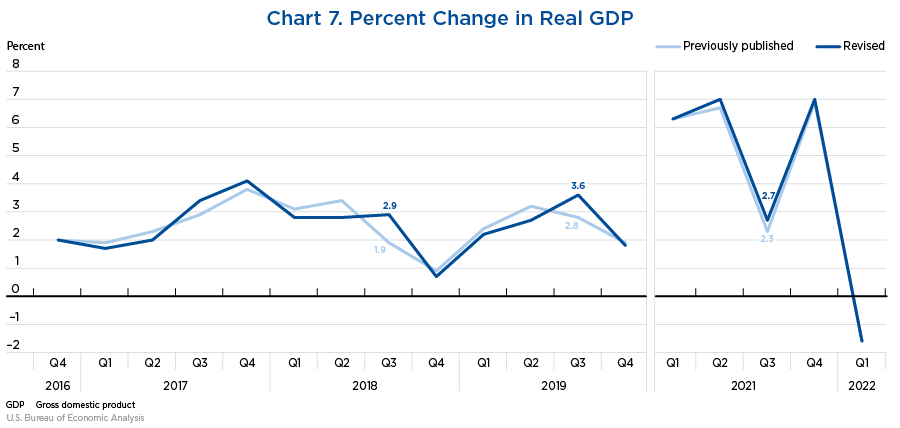

Chart 7 illustrates the revisions to real GDP for each quarter; the chart excludes 2020 because the magnitude of the pandemic-related changes in GDP in that year obscures the changes in other years. Table 7 presents the changes in 2020.

- The revisions did not reverse the direction of change in real GDP for any quarter of the revision period, and the general pattern is similar to the previously published estimates (chart 7).

- The largest revision for 2018 was to the third quarter; the upward revision was led by inventory investment, primarily in the wholesale and manufacturing industries.

- For 2019, the largest revision was to the third quarter. The upward revision (0.8 percentage point) was led by private investment in structures, in particular, petroleum and natural gas drilling.

- In the second quarter of 2020, the revision of 1.3 percentage points was led by consumer spending on services, based on newly available SAS data.

- In the third quarter of 2020, the revision of 1.5 percentage points was led by nonfarm inventory investment, primarily by manufacturing and wholesale industries.

- In the third quarter of 2021, the revision of 0.4 percentage point was led by consumer spending, particularly spending on food services, based on updated data from Census' MRTS.

- Real GDP was unrevised for the first quarter of 2022, as downward revisions to consumer spending and to private fixed equipment investment were offset by upward revisions to private inventory investment, federal government spending, and state and local government spending; imports were revised down.

| Series | Previously published | Revised | Revision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (annual rate) | |||

| 2020 Q1 | −5.1 | −4.6 | 0.5 |

| 2020 Q2 | −31.2 | −29.9 | 1.3 |

| 2020 Q3 | 33.8 | 35.3 | 1.5 |

| 2020 Q4 | 4.5 | 3.9 | −0.6 |

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 1.1.1.

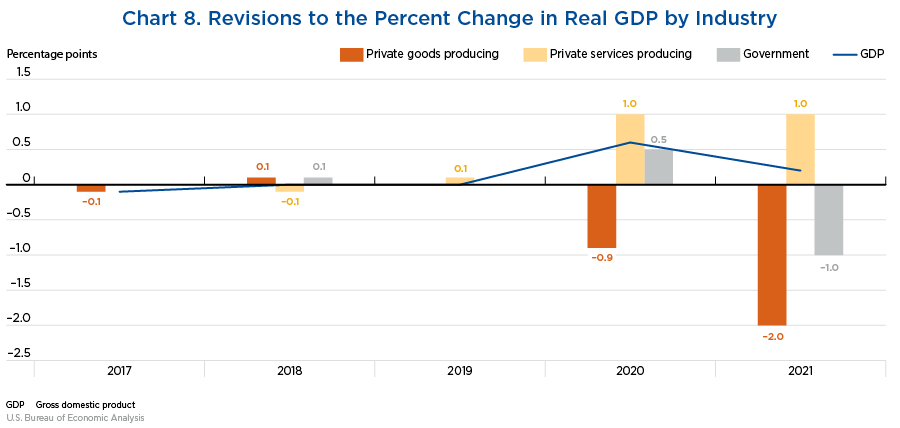

GDP by industry—or value added—which measures an industry's contribution to GDP—was largely unchanged with the annual update for 2017–2019; for 2020–2021, the updated estimates reflect upward revisions to services-producing industries and downward revisions to goods-producing industries. As with the NIPA's expenditure and income estimates, this year's revisions to the IEAs are largely driven by newly available and revised source data.

Revisions to annual percent changes in real GDP by industry for the recent period (years 2017 to 2021 and the first quarter of 2022) are discussed below. Revisions to the percent change in real GDP are presented in table 8 and illustrated in chart 8. Revisions to industry contributions to the percent change in real GDP are presented in table 9.

| Line number | Series | Share of current-dollar GDP | Change from preceding period | Revision in percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | Percent (annual rate) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product | 100.0 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 | −2.8 | 5.9 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| 2 | Private industries | 87.9 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 2.5 | −3.1 | 6.7 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| 3 | Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | 0.9 | −2.1 | 2.8 | −5.9 | 2.8 | −8.5 | −0.6 | −0.2 | 0.2 | −11.2 | −3.8 |

| 4 | Mining | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 12.6 | −1.1 | −16.3 | −0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 9.1 | −10.6 |

| 5 | Utilities | 1.6 | 1.0 | −0.3 | 0.4 | 3.6 | −4.1 | −0.2 | 0.0 | −0.8 | −0.6 | 1.5 |

| 6 | Construction | 4.1 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 1.4 | −3.8 | 2.5 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −0.7 |

| 7 | Manufacturing | 10.7 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 1.6 | −4.5 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.2 | −1.5 | −0.9 |

| 8 | Durable goods | 6.0 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 0.8 | −4.5 | 9.7 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| 9 | Nondurable goods | 4.7 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 2.7 | −4.5 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | −0.3 | −4.1 | −2.6 |

| 10 | Wholesale trade | 6.2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | −0.5 | 0.0 | 5.5 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 2.7 |

| 11 | Retail trade | 6.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.1 | −2.9 | 2.6 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| 12 | Transportation and warehousing | 3.0 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 1.0 | −12.0 | 7.5 | −0.2 | 0.2 | −0.8 | 1.4 | 4.8 |

| 13 | Information | 5.6 | 6.2 | 8.0 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 13.9 | −0.2 | 0.3 | −1.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| 14 | Finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing | 21.0 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 2.6 | −0.1 | 4.8 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | −0.4 | −0.6 |

| 15 | Finance and insurance | 8.4 | −1.7 | −0.1 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 7.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | −0.3 | −2.2 |

| 16 | Real estate and rental and leasing | 12.6 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 2.1 | −1.8 | 3.2 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.5 | 0.3 |

| 17 | Professional and business services | 13.0 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 4.3 | −1.2 | 11.7 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| 18 | Professional, scientific, and technical services | 7.9 | 3.3 | 6.0 | 4.3 | −0.1 | 11.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 19 | Management of companies and enterprises | 1.9 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 1.7 | 10.9 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| 20 | Administrative and waste management services | 3.2 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 2.6 | −5.6 | 13.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.9 | 0.1 | −1.6 |

| 21 | Educational services, health care, and social assistance | 8.6 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | −2.9 | 4.6 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 3.5 | −0.4 |

| 22 | Educational services | 1.2 | −1.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | −9.9 | 3.3 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| 23 | Health care and social assistance | 7.4 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3.0 | −1.7 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.8 | −1.0 |

| 24 | Arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, and food services | 3.9 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.9 | −27.6 | 28.3 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 2.2 | 8.4 |

| 25 | Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 0.9 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 0.9 | −36.0 | 35.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −1.5 | −0.6 | 15.4 |

| 26 | Accommodation and food services | 2.9 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 2.2 | −24.6 | 26.2 | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 6.3 |

| 27 | Other services, except government | 2.0 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.3 | −9.9 | 5.4 | −0.1 | −0.6 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 28 | Government | 12.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.6 | −0.4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | −1.0 |

| 29 | Federal | 3.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 1.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| 30 | State and local | 8.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | −1.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.7 | −1.7 |

| Addenda | ||||||||||||

| 31 | Private goods-producing industries1 | 17.1 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.1 | −3.8 | 3.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.9 | −2.0 |

| 32 | Private services-producing industries2 | 70.9 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.7 | −3.0 | 7.6 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 33 | Information-communications-technology-producing industries3 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 10.1 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 12.6 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.8 | ... |

- Consists of agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting; mining; construction; and manufacturing.

- Consists of utilities; wholesale trade; retail trade; transportation and warehousing; information; finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing; professional and business services; educational services, health care, and social assistance; arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, and food services; and other services, except government.

- Consists of computer and electronic product manufacturing (excluding navigational, measuring, electromedical, and control instruments manufacturing); software publishers; broadcasting and telecommunications; data processing, hosting and related services; internet publishing and broadcasting and web search portals; and computer systems design and related services. For 2021, revision unavailable (…); the annual update is the first estimate for the latest year.

- For 2017, the 0.1 percentage point downward revision to real GDP growth reflected downward revisions to private services-producing industries and government of less than 0.1 percentage point each and to private goods-producing industries of 0.1 percentage point. The direction of change was unrevised for all 22 industry groups.

- For 2018, real GDP growth was unrevised. Upward revisions of 0.1 percentage point to private goods-producing industries and to government were offset by a downward revision of 0.1 percentage point to private services-producing industries. The direction of change was unrevised for all 22 industry groups.

- For 2019, real GDP growth was also unrevised, reflecting small offsetting revisions across industries, notably an upward revision to finance and insurance and a downward revision to information. An upward revision of 0.1 percentage point to private services-producing industries was offset by downward revisions of less than 0.1 percentage point to private goods-producing industries and to government. The direction of change was unrevised for all 22 industry groups.

- For 2020, the 0.6 percentage point upward revision to the decrease in real GDP reflected upward revisions to private services-producing industries and government that were partly offset by a downward revision to private goods-producing industries. The direction of change was unrevised for all 22 industry groups.

- Private services-producing industries was revised up 1.0 percentage point, primarily reflecting upward revisions to health care and social assistance; professional, scientific, and technical services; wholesale trade; and accommodation and food services.

- Government was revised up 0.5 percentage point, led by an upward revision to state and local government.

- Private goods-producing industries was revised down 0.9 percentage point, led by downward revisions to nondurable goods manufacturing and to agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting.

- For 2021, the 0.2 percentage point upward revision to real GDP growth reflected an upward revision to private services-producing industries that was partly offset by downward revisions to private goods-producing industries and government. The direction of change was unrevised for all 22 industry groups.

- Private services-producing industries was revised up 1.0 percentage point, primarily reflecting upward revisions to wholesale trade; accommodation and food services; and professional, scientific, and technical services that were partly offset by downward revisions to finance and insurance; health care and social assistance; and administrative and waste management services.

- Private goods-producing industries was revised down 2.0 percentage points, led by downward revisions to mining and nondurable goods manufacturing.

- Government was revised down 1.0 percentage point, reflecting a downward revision to state and local government that was partly offset by an upward revision to federal government.

- In the first quarter of 2022, real GDP was unrevised. Private goods-producing industries was revised up 3.2 percentage points, private services-producing industries was revised down 0.8 percentage point, and government was revised down 0.2 percentage point.

| Line number | Series | Contributions to percent change | Revision in contributions to percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percentage points) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| Percent change at annual rate: | |||||||||||

| 1 | Gross domestic product | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 | −2.8 | 5.9 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Percentage points at annual rates: | |||||||||||

| 2 | Private industries | 2.08 | 2.79 | 2.23 | −2.76 | 5.83 | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.36 |

| 3 | Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.04 |

| 4 | Mining | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.18 | −0.02 | −0.21 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.15 |

| 5 | Utilities | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| 6 | Construction | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.16 | 0.10 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.04 |

| 7 | Manufacturing | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.18 | −0.50 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.18 | −0.09 |

| 8 | Durable goods | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.05 | −0.28 | 0.57 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| 9 | Nondurable goods | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.13 | −0.22 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.20 | −0.12 |

| 10 | Wholesale trade | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.34 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.17 |

| 11 | Retail trade | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.12 | −0.16 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 12 | Transportation and warehousing | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.03 | −0.38 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| 13 | Information | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| 14 | Finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.54 | −0.01 | 1.02 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.07 | −0.14 |

| 15 | Finance and insurance | −0.14 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.61 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.02 | −0.16 |

| 16 | Real estate and rental and leasing | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.28 | −0.23 | 0.42 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| 17 | Professional and business services | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.54 | −0.15 | 1.47 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| 18 | Professional, scientific, and technical services | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.32 | −0.01 | 0.85 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| 19 | Management of companies and enterprises | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.21 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| 20 | Administrative and waste management services | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.18 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.05 |

| 21 | Educational services, health care, and social assistance | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.25 | −0.25 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.31 | −0.03 |

| 22 | Educational services | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| 23 | Health care and social assistance | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.22 | −0.13 | 0.36 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.28 | −0.06 |

| 24 | Arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, and food services | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −1.19 | 0.91 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.27 |

| 25 | Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.41 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| 26 | Accommodation and food services | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.78 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

| 27 | Other services, except government | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.21 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| 28 | Government | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | −0.12 |

| 29 | Federal | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| 30 | State and local | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.16 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.14 |

| Addenda | |||||||||||

| 31 | Private goods-producing industries1 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 0.37 | −0.66 | 0.53 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.17 | −0.30 |

| 32 | Private services-producing industries2 | 1.57 | 2.18 | 1.85 | −2.10 | 5.30 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.66 |

| 33 | Information-communications-technology-producing industries3 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.93 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.06 | ... |

- Consists of agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting; mining; construction; and manufacturing.

- Consists of utilities; wholesale trade; retail trade; transportation and warehousing; information; finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing; professional and business services; educational services, health care, and social assistance; arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, and food services; and other services, except government.

- Consists of computer and electronic product manufacturing (excluding navigational, measuring, electromedical, and control instruments manufacturing); software publishers; broadcasting and telecommunications; data processing, hosting and related services; internet publishing and broadcasting and web search portals; and computer systems design and related services. For 2021, revision unavailable (…); the annual update is the first estimate for the latest year.

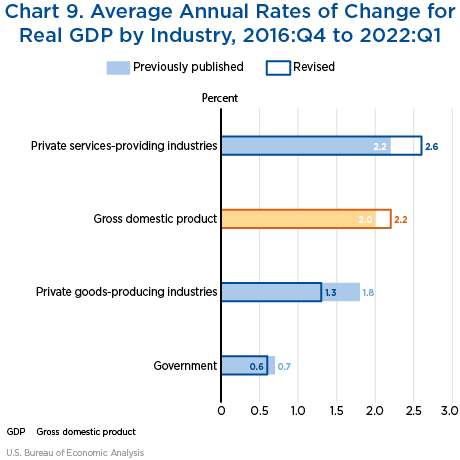

As noted above, from the fourth quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2022, the average annual change in real GDP was revised up from 2.0 to 2.2 percent. Chart 9 illustrates the revisions to the percent change for private goods-producing industries, private services-producing industries, and government over the period. Private services-producing industries increased more than previously estimated over the period, while private goods-producing industries and government increased less.

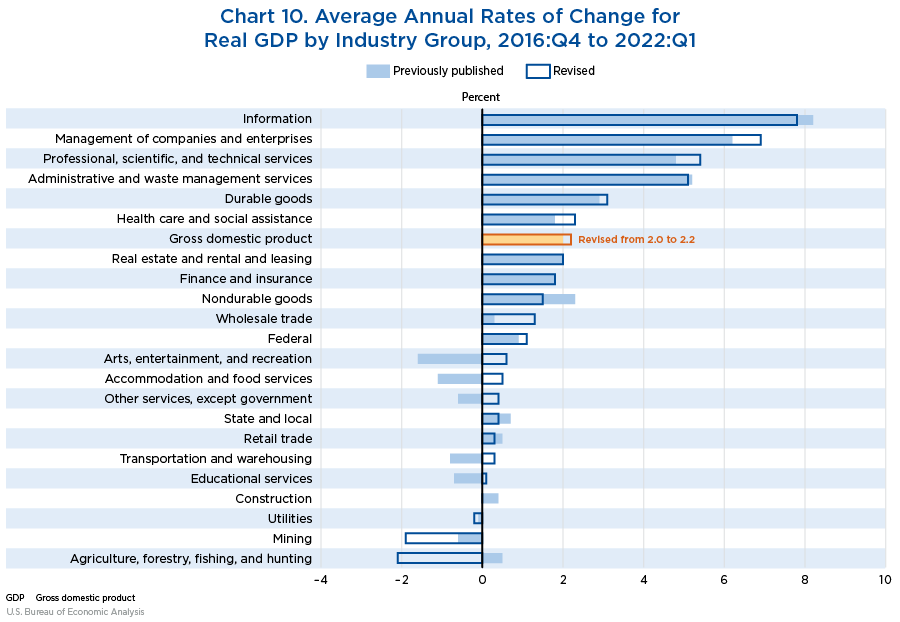

Chart 10 provides detail for 22 industry groups and illustrates that the direction of change over the period from the fourth quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of 2022 was reversed for 6 industries. The updated estimates show an increase over the period, rather than a decrease, for educational services; transportation and warehousing; "other" services, except government; accommodation and food services; and arts, entertainment, and recreation. The updated estimates show a decrease over the period, rather than an increase, for the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industry group. The largest revisions over the period were to the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industry group (revised down from 0.5 percent to −2.6 percent) and to the arts, entertainment, and recreation industry group (revised up from −1.6 percent to 0.6 percent).

Notable industry revisions

As shown in Table 9, most industries show minimal or no revisions for 2017 and 2018, small revisions for 2019, and larger revisions for 2020. Revisions for 2019 and 2020 mainly reflect the incorporation of new and revised IRS SOI data. The sources of revision are more mixed for 2021, notably:

- For the mining industry, revisions throughout the update period were primarily to the oil and gas extraction industry; revisions for 2021 reflect the incorporation of revised data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

- For nondurable-goods manufacturing, revisions were primarily to the petroleum and coal products manufacturing industry and reflect the incorporation of revised EIA data.

- For wholesale trade, revisions for 2021 reflect the incorporation of benchmarked Census Monthly Wholesale Trade Survey data as well as the incorporation of revised BLS PPIs.

- For the health care and social assistance industry group, revisions were primarily to ambulatory health care services and hospitals. Revisions for 2020 largely reflect revised subsidies data in addition to newly available IRS SOI data. For 2021, the revisions largely reflect the incorporation of revised Census QSS data as well as BLS PPIs.

- For the accommodation and food services industry group, revisions were led by the food services and drinking places industry, and revisions for 2021 reflect revised Census MRTS data as well as BLS QCEW wage data.

Appendix A: Impacts of the Annual Update on GDP Expenditure Components

| Line number | Series | Change from preceding period | Revision in percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (annual rate) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Personal consumption expenditures | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.0 | −3.0 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 2 | Goods | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 12.2 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| 3 | Durable goods | 6.4 | 6.8 | 3.8 | 10.0 | 18.5 | 0.1 | −0.2 | −0.5 | 2.3 | 0.4 |

| 4 | Motor vehicles and parts | 4.9 | 3.7 | −1.5 | 1.6 | 15.8 | 0.1 | −0.4 | −0.3 | −1.7 | 0.8 |

| 5 | Furnishings and durable household equipment | 7.6 | 8.4 | 3.4 | 13.4 | 14.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 5.8 | −0.2 |

| 6 | Recreational goods and vehicles | 9.3 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 24.3 | 20.1 | 0.2 | −0.5 | −1.0 | 6.1 | 0.9 |

| 7 | Other durable goods | 3.0 | 5.6 | 3.9 | −2.3 | 31.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | −0.6 | −0.8 | −1.2 |

| 8 | Nondurable goods | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 8.8 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.4 | −0.3 |

| 9 | Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | 3.6 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −1.9 | −0.7 |

| 10 | Clothing and footwear | 1.9 | 2.7 | 3.1 | −5.0 | 26.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −1.0 | −0.6 |

| 11 | Gasoline and other energy goods | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.3 | −13.2 | 11.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.5 | 1.9 |

| 12 | Other nondurable goods | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.3 | 1.0 | −0.2 |

| 13 | Services | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.5 | −6.6 | 6.3 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| 14 | Household consumption expenditures (for services) | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.7 | −7.5 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| 15 | Housing and utilities | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 |

| 16 | Health care | 2.1 | 2.6 | 3.5 | −7.4 | 7.3 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| 17 | Transportation services | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.3 | −24.9 | 15.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.9 | 3.6 |

| 18 | Recreation services | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.5 | −26.1 | 16.6 | −0.2 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 4.0 | 0.0 |

| 19 | Food services and accommodations | 2.7 | 2.9 | 1.9 | −21.0 | 23.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| 20 | Financial services and insurance | 1.6 | 1.4 | −3.1 | 1.6 | 3.9 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −2.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 |

| 21 | Other services | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.9 | −7.3 | 9.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 2.6 | 1.6 |

| 22 | Final consumption expenditures of nonprofit institutions serving households | −0.6 | 4.2 | −3.4 | 12.9 | −14.6 | −1.0 | 0.1 | 0.8 | −3.3 | −1.1 |

| 23 | Gross output of nonprofit institutions | 0.7 | 2.6 | 1.4 | −1.7 | 0.9 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| 24 | Less: Receipts from sales of goods and services by nonprofit institutions | 1.2 | 2.1 | 3.3 | −6.9 | 7.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.5 |

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 2.3.1.

| Line number | Series | Contributions to percent change | Revision in contributions to percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percentage points) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| Percent change at annual rate: | |||||||||||

| 1 | Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.0 | −3.0 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Percentage points at annual rates: | |||||||||||

| 2 | Goods | 1.21 | 1.23 | 0.97 | 1.6 | 4.06 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| 3 | Durable goods | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.39 | 1.04 | 2.18 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.24 | 0.11 |

| 4 | Motor vehicles and parts | 0.18 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.62 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| 5 | Furnishings and durable household equipment | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| 6 | Recreational goods and vehicles | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.68 | 0.7 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| 7 | Other durable goods | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| 8 | Nondurable goods | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 1.89 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.06 |

| 9 | Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.3 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.14 | −0.06 |

| 10 | Clothing and footwear | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.66 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.02 |

| 11 | Gasoline and other energy goods | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.28 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| 12 | Other nondurable goods | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.7 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.02 |

| 13 | Services | 1.17 | 1.65 | 1.01 | −4.59 | 4.23 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.14 | 0.62 | 0.38 |

| 14 | Household consumption expenditures (for services) | 1.19 | 1.52 | 1.12 | −4.98 | 4.76 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.16 | 0.73 | 0.4 |

| 15 | Housing and utilities | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0 |

| 16 | Health care | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.59 | −1.27 | 1.21 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| 17 | Transportation services | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.11 | −0.84 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 |

| 18 | Recreation services | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −1.06 | 0.51 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| 19 | Food services and accommodations | 0.19 | 0.2 | 0.13 | −1.48 | 1.37 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 20 | Financial services and insurance | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.26 | 0.12 | 0.32 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.16 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| 21 | Other services | 0.3 | 0.29 | 0.32 | −0.62 | 0.72 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| 22 | Final consumption expenditures of nonprofit institutions serving households | −0.02 | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.39 | −0.53 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −0.03 |

| 23 | Gross output of nonprofit institutions | 0.08 | 0.3 | 0.16 | −0.19 | 0.1 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| 24 | Less: Receipts from sales of goods and services by nonprofit institutions | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.27 | −0.59 | 0.63 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.05 |

Note. Contributions are from NIPA table 2.3.2.

| Line number | Series | Change from preceding period | Revision in percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (annual rate) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Private fixed investment | 4.1 | 4.9 | 2.5 | −2.3 | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.7 | 0.4 | −0.4 |

| 2 | Nonresidential | 4.1 | 6.5 | 3.6 | −4.9 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.7 | 0.4 | −1.0 |

| 3 | Structures | 4.4 | 4.1 | 2.3 | −10.1 | −6.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| 4 | Commercial and health care | 3.2 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 3.2 | −7.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 0.0 |

| 5 | Manufacturing | −13.5 | −1.8 | 5.6 | −9.5 | −0.7 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 0.5 |

| 6 | Power and communication | −4.6 | −5.7 | 7.4 | −1.7 | −8.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 5.8 |

| 7 | Mining exploration, shafts, and wells | 40.4 | 27.8 | −0.3 | −38.4 | 14.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.3 | −0.9 | 2.7 |

| 8 | Other structures | 3.9 | 1.4 | −0.6 | −12.9 | −17.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.4 |

| 9 | Equipment | 2.8 | 6.6 | 1.3 | −10.5 | 10.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −2.0 | −2.2 | −2.8 |

| 10 | Information processing equipment | 7.1 | 7.8 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 9.8 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −1.1 | −5.5 | −4.8 |

| 11 | Computers and peripheral equipment | 6.7 | 13.6 | 1.8 | 11.6 | 7.7 | 1.0 | 0.0 | −1.4 | 1.4 | −5.2 |

| 12 | Other | 7.3 | 5.4 | 3.0 | −3.2 | 10.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −1.0 | −8.6 | −4.6 |

| 13 | Industrial equipment | 4.5 | 5.9 | 3.4 | −8.2 | 11.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.2 | −3.3 | −2.1 |

| 14 | Transportation equipment | −1.4 | 5.1 | −3.2 | −30.6 | 15.7 | −0.4 | 0.2 | −6.0 | 4.6 | 1.1 |

| 15 | Other equipment | 0.1 | 7.1 | 2.6 | −7.0 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −1.7 | −5.4 | −3.0 |

| 16 | Intellectual property products | 5.6 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 4.8 | 9.7 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.0 | −0.3 |

| 17 | Software | 10.8 | 11.6 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 12.8 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.3 | −0.5 |

| 18 | Research and development | 1.9 | 6.2 | 8.7 | 3.4 | 8.7 | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 0.4 |

| 19 | Entertainment, literary, and artistic originals | 3.3 | 3.4 | 1.3 | −5.6 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.9 | 1.3 | −4.2 |

| 20 | Residential | 4.0 | −0.6 | −1.0 | 7.2 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| 21 | Structures | 4.0 | −0.6 | −1.0 | 7.2 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| 22 | Permanent site | 4.4 | 1.8 | −4.4 | 7.1 | 19.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| 23 | Single family | 6.7 | 2.8 | −6.3 | 6.2 | 22.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 4.1 |

| 24 | Multifamily | −4.4 | −2.0 | 4.3 | 10.6 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.4 | −7.8 |

| 25 | Other structures | 3.6 | −2.6 | 1.7 | 7.3 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −0.2 | 1.1 |

| 26 | Equipment | 6.6 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 7.1 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | −0.4 |

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 5.3.1.

| Line number | Series | Contributions to percent change | Revision in contributions to percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percentage points) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| Percent change at annual rate: | |||||||||||

| 1 | Private fixed investment | 4.1 | 4.9 | 2.5 | −2.3 | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.7 | 0.4 | −0.4 |

| Percentage points at annual rates: | |||||||||||

| 2 | Nonresidential | 3.19 | 5.01 | 2.76 | −3.85 | 4.75 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.61 | 0.33 | −0.78 |

| 3 | Structures | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.41 | −1.83 | −1.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 0.22 |

| 4 | Commercial and health care | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.18 | −0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | −0.02 |

| 5 | Manufacturing | −0.33 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.20 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| 6 | Power and communication | −0.18 | −0.21 | 0.25 | −0.06 | −0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| 7 | Mining exploration, shafts, and wells | 0.97 | 0.86 | −0.01 | −1.28 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.06 |

| 8 | Other structures | 0.14 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.46 | −0.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| 9 | Equipment | 0.96 | 2.17 | 0.42 | −3.36 | 2.96 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.67 | −0.65 | −0.96 |

| 10 | Information processing equipment | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 1.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.58 | −0.61 |

| 11 | Computers and peripheral equipment | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.19 |

| 12 | Other | 0.57 | 0.42 | 0.22 | −0.23 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.62 | −0.44 |

| 13 | Industrial equipment | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.23 | −0.56 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.23 | −0.16 |

| 14 | Transportation equipment | −0.13 | 0.44 | −0.28 | −2.45 | 0.83 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.52 | 0.53 | 0.05 |

| 15 | Other equipment | 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.18 | −0.49 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.38 | −0.24 |

| 16 | Intellectual property products | 1.46 | 2.11 | 1.94 | 1.33 | 2.86 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.55 | −0.04 |

| 17 | Software | 1.12 | 1.24 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 1.55 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.04 |

| 18 | Research and development | 0.25 | 0.78 | 1.13 | 0.48 | 1.31 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.09 |

| 19 | Entertainment, literary, and artistic originals | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.09 |

| 20 | Residential | 0.90 | −0.13 | −0.22 | 1.58 | 2.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| 21 | Structures | 0.87 | −0.14 | −0.23 | 1.56 | 2.66 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.47 |

| 22 | Permanent site | 0.43 | 0.19 | −0.44 | 0.67 | 2.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| 23 | Single family | 0.52 | 0.22 | −0.51 | 0.47 | 1.95 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| 24 | Multifamily | −0.09 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | −0.15 |

| 25 | Other structures | 0.44 | −0.32 | 0.21 | 0.89 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.22 |

| 26 | Equipment | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

Note. Contributions are from NIPA table 5.3.2.

| Line number | Series | Level | Revision in level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Change in private inventories | 36.3 | 66.1 | 73.1 | −54.6 | −19.4 | 2.7 | 0.4 | −2.0 | −12.3 | 13.2 |

| 2 | Farm | −7.0 | −10.1 | −18.7 | −8.4 | −3.9 | −0.5 | −0.9 | −1.5 | −0.7 | 19.0 |

| 3 | Mining, utilities, and construction | −13.7 | −11.2 | 14.6 | 0.7 | −9.5 | 1.2 | −0.1 | 0.6 | 4.8 | −10.2 |

| 4 | Manufacturing | 5.0 | 18.6 | 46.5 | −28.6 | −46.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.4 | −19.0 | −10.7 |

| 5 | Durable-goods industries | −1.0 | 12.2 | 28.8 | −10.8 | −28.3 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 2.5 | −5.1 | 5.1 |

| 6 | Nondurable-goods industries | 6.6 | 6.2 | 17.3 | −18.7 | −17.5 | −0.2 | 0.2 | −3.4 | −14.7 | −17.7 |

| 7 | Wholesale trade | 30.2 | 33.2 | 21.6 | −24.4 | 26.2 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −10.2 | −8.1 |

| 8 | Durable-goods industries | 20.2 | 33.3 | 11.2 | −28.4 | 31.8 | 0.8 | 0.4 | −1.0 | −2.9 | −0.2 |

| 9 | Nondurable-goods industries | 9.8 | −0.7 | 10.4 | 4.3 | −5.9 | 0.8 | −0.3 | 1.2 | −7.5 | −8.2 |

| 10 | Retail trade | 15.9 | 25.3 | 9.4 | −7.1 | −12.5 | −0.8 | 0.2 | −1.3 | 11.4 | 6.6 |

| 11 | Motor vehicle and parts dealers | 12.7 | 18.3 | 5.2 | −17.0 | −45.3 | 0.5 | −1.0 | −1.3 | 5.5 | 0.5 |

| 12 | Food and beverage stores | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −0.1 | −0.2 |

| 13 | General merchandise stores | −3.1 | 2.0 | −1.8 | 0.6 | 10.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −2.0 | 2.8 |

| 14 | Other retail stores | 4.7 | 3.9 | 5.4 | 7.4 | 22.5 | −1.3 | 1.0 | −0.3 | 8.3 | 3.7 |

| 15 | Other industries | 3.2 | 6.7 | −1.4 | 11.0 | 25.8 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 17.3 |

| 16 | Residual | 2.0 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

Note. Levels are from NIPA table 5.7.6B. The chained-dollar series are calculated as the period-to-period change in end-of-period inventories. Because the formula for the chain-type quantity indexes uses weights of more than one period, chained-dollar estimates are usually not additive.

| Line number | Series | Change from preceding period | Revision in change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Change in private inventories | 0.6 | 29.8 | 7.0 | −127.7 | 35.2 | 2.7 | −2.3 | −2.4 | −10.3 | 25.5 |

| 2 | Farm | −0.2 | −3.1 | −8.7 | 10.3 | 4.5 | −0.5 | −0.4 | −0.6 | 0.8 | 19.7 |

| 3 | Mining, utilities, and construction | −21.9 | 2.5 | 25.7 | −13.9 | −10.2 | 1.2 | −1.3 | 0.7 | 4.2 | −15.0 |

| 4 | Manufacturing | 3.1 | 13.6 | 27.9 | −75.1 | −17.4 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.4 | −18.5 | 8.2 |

| 5 | Durable-goods industries | 13.3 | 13.2 | 16.7 | −39.6 | −17.5 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 2.7 | −7.6 | 10.2 |

| 6 | Nondurable-goods industries | −12.2 | −0.4 | 11.1 | −35.9 | 1.2 | −0.2 | 0.4 | −3.6 | −11.3 | −2.9 |

| 7 | Wholesale trade | 15.4 | 3.0 | −11.6 | −46.0 | 50.6 | 1.7 | −1.5 | 0.1 | −10.5 | 2.2 |

| 8 | Durable-goods industries | 16.5 | 13.1 | −22.2 | −39.5 | 60.2 | 0.8 | −0.5 | −1.3 | −1.9 | 2.7 |

| 9 | Nondurable-goods industries | −1.6 | −10.5 | 11.1 | −6.1 | −10.2 | 0.8 | −1.1 | 1.5 | −8.7 | −0.7 |

| 10 | Retail trade | −8.7 | 9.4 | −16.0 | −16.5 | −5.4 | −0.8 | 1.0 | −1.5 | 12.8 | −4.8 |

| 11 | Motor vehicle and parts dealers | −5.1 | 5.6 | −13.0 | −22.2 | −28.4 | 0.5 | −1.5 | −0.3 | 6.8 | −5.0 |

| 12 | Food and beverage stores | 0.4 | −0.4 | −1.0 | 0.4 | −1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −0.3 | −0.1 |

| 13 | General merchandise stores | −2.3 | 5.2 | −3.8 | 2.4 | 9.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −2.0 | 4.8 |

| 14 | Other retail stores | −1.7 | −0.8 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 15.1 | −1.3 | 2.3 | −1.3 | 8.6 | −4.6 |

| 15 | Other industries | 11.7 | 3.6 | −8.1 | 12.4 | 14.8 | 1.2 | −0.3 | −0.6 | 0.7 | 16.4 |

Note. Level changes are calculated from NIPA table 5.7.6B.The chained-dollar series are calculated as the period-to-period change in end-of-period inventories. Because the formula for the chain-type quantity indexes uses weights of more than one period, chained-dollar estimates are usually not additive.

| Line number | Series | Change from preceding period | Revision in percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (annual rate) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

| 1 | Exports of goods and services | 4.3 | 2.8 | 0.5 | −13.2 | 6.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| 2 | Exports of goods | 4.1 | 4.2 | 0.1 | −10.1 | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.2 |

| 3 | Foods, feeds, and beverages | 0.4 | −0.1 | −1.3 | 4.9 | −4.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.3 |

| 4 | Industrial supplies and materials | 8.7 | 6.7 | 3.4 | −2.9 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 |

| 5 | Capital goods, except automotive | 2.5 | 4.7 | −2.6 | −16.2 | 10.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | −0.5 |