GDP and the Economy

Advance Estimates for the Fourth Quarter of 2020

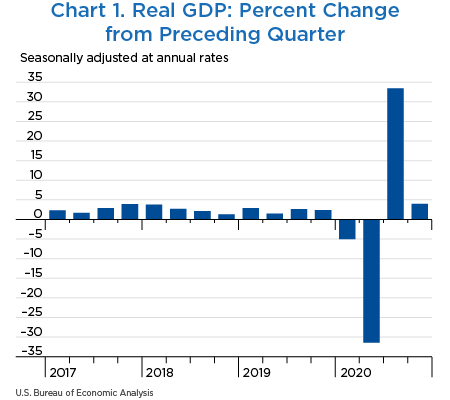

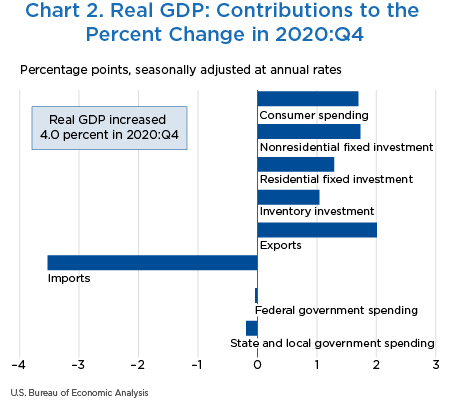

Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 4.0 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020, according to the “advance” estimates of the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) (chart 1 and table 1).1 In the third quarter, real GDP increased 33.4 percent. The increase in real GDP in the fourth quarter reflected increases in exports, nonresidential fixed investment, consumer spending, residential fixed investment, and private inventory investment that were partly offset by decreases in state and local government spending and federal government spending.2 Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased (chart 2).

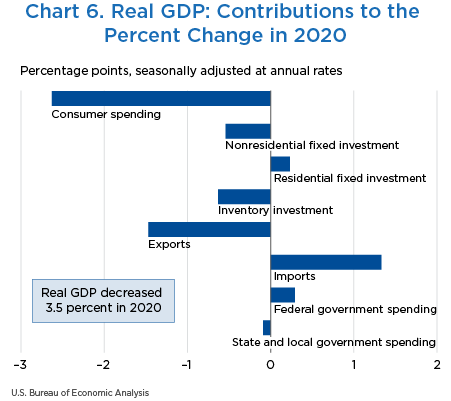

In 2020 (from the 2019 annual level to the 2020 annual level), real GDP decreased 3.5 percent after increasing 2.2 percent in 2019 (see “Real GDP, 2020”).

The slowdown in real GDP growth in the fourth quarter followed a record quarterly GDP growth rate in the third quarter, and continued the economic recovery from the sharp decreases earlier in the year at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Led by a slowdown in consumer spending, most GDP components contributed to the slowdown, except for federal government spending and state and local government spending. Imports slowed.

- The slowdown in consumer spending reflected a downturn in spending on goods and a smaller increase in spending on services.

- Within goods, all components of both durable and nondurable goods contributed to the downturn. The leading contributors were sharp slowdowns in spending on clothing and footwear and on motor vehicles and parts.

- Within services, the leading contributors to the smaller increase were a sharp slowdown in spending on health care and a downturn in spending on food services and accommodations.

- A smaller increase in private inventory investment was the second largest contributor to the slowdown in real GDP. The slowdown was more than accounted for by a downturn in inventory investment by motor vehicle dealers. A notable offset was an upturn in inventories for petroleum and coal product manufacturing.

- Exports slowed, reflecting a sharp slowdown in exports of goods (mainly automotive vehicles, engines, and parts) that was partly offset by an upturn in exports of services (more than accounted for by travel services).

- Nonresidential fixed investment slowed, reflecting slowdowns in investment in equipment and intellectual property products that were partly offset by an upturn in investment in structures.

- The slowdown in equipment investment mainly reflected a slowdown in spending on transportation equipment.

- Within intellectual property products, slowdowns in research and development and in software were partly offset by a smaller decrease in entertainment, literary, and artistic originals.

- The upturn in structures was more than accounted for by an upturn in mining exploration, shafts, and wells.

- Imports slowed. As a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, imports were an offset to the slowdown in fourth-quarter GDP. The main contributor was a slowdown in automotive vehicles, engines, and parts.

| Line | Series | Share of current-dollar GDP (percent) | Change from preceding period (percent) | Contribution to percent change in real GDP (percentage points) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | ||||||||

| Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product1 | 100.0 | −5.0 | −31.4 | 33.4 | 4.0 | −5.0 | −31.4 | 33.4 | 4.0 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 67.7 | −6.9 | −33.2 | 41.0 | 2.5 | −4.75 | −24.01 | 25.44 | 1.70 |

| 3 | Goods | 22.6 | 0.1 | −10.8 | 47.2 | −0.4 | 0.03 | −2.06 | 9.55 | −0.10 |

| 4 | Durable goods | 8.2 | −12.5 | −1.7 | 82.7 | 0.0 | −0.93 | 0.00 | 5.20 | 0.00 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | 14.5 | 7.1 | −15.0 | 31.1 | −0.7 | 0.97 | −2.05 | 4.35 | −0.10 |

| 6 | Services | 45.1 | −9.8 | −41.8 | 38.0 | 4.0 | −4.78 | −21.95 | 15.89 | 1.80 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 18.2 | −9.0 | −46.6 | 86.3 | 25.3 | −1.56 | −8.77 | 11.96 | 4.06 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 18.0 | −1.4 | −29.2 | 31.3 | 18.4 | −0.23 | −5.27 | 5.39 | 3.02 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 13.4 | −6.7 | −27.2 | 22.9 | 13.8 | −0.91 | −3.67 | 3.20 | 1.73 |

| 10 | Structures | 2.6 | −3.7 | −33.6 | −17.4 | 3.0 | −0.11 | −1.11 | −0.53 | 0.08 |

| 11 | Equipment | 5.9 | −15.2 | −35.9 | 68.2 | 24.9 | −0.91 | −2.03 | 3.26 | 1.30 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 4.9 | 2.4 | −11.4 | 8.4 | 7.5 | 0.11 | −0.53 | 0.46 | 0.35 |

| 13 | Residential | 4.6 | 19.0 | −35.6 | 63.0 | 33.5 | 0.68 | −1.60 | 2.19 | 1.29 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | 0.2 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... | −1.34 | −3.50 | 6.57 | 1.04 |

| 15 | Net exports of goods and services | −3.7 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... | 1.13 | 0.62 | −3.21 | −1.52 |

| 16 | Exports | 10.3 | −9.5 | −64.4 | 59.6 | 22.0 | −1.12 | −9.51 | 4.89 | 2.01 |

| 17 | Goods | 7.1 | −2.7 | −66.8 | 104.3 | 31.1 | −0.20 | −6.56 | 4.87 | 1.88 |

| 18 | Services | 3.2 | −20.8 | −59.6 | −0.5 | 4.3 | −0.92 | −2.95 | 0.03 | 0.14 |

| 19 | Imports | 14.0 | −15.0 | −54.1 | 93.1 | 29.5 | 2.25 | 10.13 | −8.10 | −3.53 |

| 20 | Goods | 11.9 | −11.4 | −49.6 | 110.2 | 30.8 | 1.36 | 7.32 | −7.67 | −3.11 |

| 21 | Services | 2.1 | −28.5 | −69.9 | 24.9 | 22.2 | 0.90 | 2.80 | −0.43 | −0.42 |

| 22 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 17.8 | 1.3 | 2.5 | −4.8 | −1.2 | 0.22 | 0.77 | −0.75 | −0.22 |

| 23 | Federal | 7.0 | 1.6 | 16.4 | −6.2 | −0.5 | 0.10 | 1.17 | −0.38 | −0.04 |

| 24 | National defense | 4.2 | −0.3 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 5.0 | −0.01 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| 25 | Nondefense | 2.7 | 4.4 | 37.6 | −18.3 | −8.4 | 0.11 | 0.98 | −0.55 | −0.24 |

| 26 | State and local | 10.9 | 1.1 | −5.4 | −3.9 | −1.7 | 0.12 | −0.40 | −0.37 | −0.19 |

| Addenda: | ||||||||||

| 27 | Gross domestic income (GDI)2 | ...... | −2.5 | −32.6 | 25.8 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| 28 | Average of GDP and GDI | ...... | −3.7 | −32.0 | 29.6 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| 29 | Final sales of domestic product | 99.8 | −3.6 | −28.1 | 25.9 | 3.0 | −3.62 | −27.88 | 26.87 | 2.97 |

| 30 | Goods | 30.9 | −3.5 | −29.0 | 62.4 | 4.7 | −0.98 | −7.40 | 17.42 | 1.45 |

| 31 | Services | 60.2 | −7.6 | −32.9 | 23.7 | 2.0 | −4.82 | −21.32 | 14.60 | 1.19 |

| 32 | Structures | 8.9 | 10.3 | −28.4 | 14.9 | 16.8 | 0.85 | −2.66 | 1.42 | 1.37 |

| 33 | Motor vehicle output | 2.9 | −24.7 | −86.9 | 1,133.9 | −10.6 | −0.73 | −3.99 | 5.92 | −0.33 |

| 34 | GDP excluding motor vehicle output | 97.1 | −4.4 | −29.0 | 26.7 | 4.5 | −4.23 | −27.39 | 27.52 | 4.34 |

- The GDP estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

- GDI is deflated by the implicit price deflator for GDP. Not estimated with the Q4 advance or second estimates.

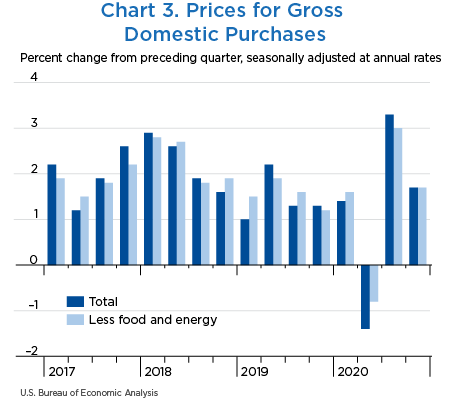

Prices for gross domestic purchases—goods and services purchased by U.S. residents—increased 1.7 percent in the fourth quarter after increasing 3.3 percent in the third quarter (table 2 and chart 3). The leading contributors to the slowdown were smaller increases in the prices paid for consumer spending, mainly motor vehicles and parts and gasoline and other energy goods. Notable offsets included an upturn in prices for consumer spending on transportation services and a smaller decrease in prices for food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption.

Food prices decreased 0.3 percent in the fourth quarter after decreasing 1.7 percent in the third quarter. Prices for energy goods and services increased 8.4 percent after increasing 27.4 percent. Gross domestic purchases prices excluding food and energy increased 1.7 percent after increasing 3.0 percent.

Consumer prices excluding food and energy, a measure of the “core” rate of inflation, slowed, increasing 1.4 percent in the fourth quarter after increasing 3.4 percent in the third quarter.

| Line | Series | Change from preceding period (percent) | Contribution to percent change in gross domestic purchases prices (percentage points) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2020 | ||||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic purchases1 | 1.4 | −1.4 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 1.4 | −1.4 | 3.3 | 1.7 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 1.3 | −1.6 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 0.85 | −1.06 | 2.39 | 1.00 |

| 3 | Goods | −0.9 | −5.6 | 5.4 | −0.2 | −0.19 | −1.21 | 1.18 | −0.04 |

| 4 | Durable goods | −1.7 | −3.1 | 8.2 | 0.0 | −0.12 | −0.23 | 0.62 | 0.00 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | −0.5 | −6.8 | 4.0 | −0.3 | −0.07 | −0.98 | 0.56 | −0.04 |

| 6 | Services | 2.3 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 1.04 | 0.15 | 1.21 | 1.04 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 1.8 | −0.1 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.27 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.30 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| 10 | Structures | 1.5 | −1.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 11 | Equipment | 0.7 | 0.0 | −0.6 | −1.6 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.09 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 0.9 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 3.0 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| 13 | Residential | 2.3 | 1.0 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.25 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.05 | −0.04 |

| 15 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 1.8 | −1.9 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 0.31 | −0.35 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| 16 | Federal | −0.3 | −1.1 | 1.7 | 2.3 | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.12 | 0.16 |

| 17 | National defense | −0.1 | −2.5 | 2.0 | 2.7 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| 18 | Nondefense | −0.5 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| 19 | State and local | 3.1 | −2.4 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 0.32 | −0.28 | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| Addenda: | |||||||||

| Gross domestic purchases: | |||||||||

| 20 | Food | 3.2 | 15.7 | −1.7 | −0.3 | 0.15 | 0.77 | −0.09 | −0.01 |

| 21 | Energy goods and services | −7.0 | −45.7 | 27.4 | 8.4 | −0.19 | −1.47 | 0.59 | 0.18 |

| 22 | Excluding food and energy | 1.6 | −0.8 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.49 | −0.71 | 2.80 | 1.58 |

| Personal consumption expenditures: | |||||||||

| 23 | Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | 3.1 | 15.4 | −1.9 | −0.6 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| 24 | Energy goods and services | −9.8 | −44.9 | 24.9 | 10.6 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| 25 | Excluding food and energy | 1.6 | −0.8 | 3.4 | 1.4 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| 26 | Gross domestic product | 1.4 | −1.8 | 3.5 | 2.0 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| 27 | Exports of goods and services | −2.5 | −18.8 | 12.8 | 5.6 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| 28 | Imports of goods and services | −1.4 | −12.8 | 8.6 | 2.3 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

- The estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

Note. Most percent changes are from NIPA table 1.6.7; percent changes for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) for food and energy goods and services and for PCE excluding food and energy are from NIPA table 2.3.7. Contributions are from NIPA table 1.6.8. GDP, export, and import prices are from NIPA table 1.1.7.

Measured in current dollars, personal income decreased $339.7 billion in the fourth quarter, compared with a decrease of $541.5 billion in the third quarter (table 3). The decrease in personal income was more than accounted for by decreases in personal current transfer receipts (notably, government social benefits related to the winding down of Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act pandemic relief programs) and proprietors' income that were partly offset by increases in compensation and personal dividend income. The addenda lines in table 3 include detail on the effects of selected federal pandemic response programs on personal income.

- Within government social benefits, unemployment insurance and “other” social benefits decreased, primarily reflecting declines in Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program payments and Lost Wages Assistance program benefits, both of which aid individuals impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Within proprietors' income, a decrease in nonfarm proprietors' income was partly offset by an increase in farm proprietors' income.

- In nonfarm proprietors' income, the decrease primarily reflected a decline in Paycheck Protection Program loans.

- In farm proprietors' income, the increase primarily reflected an increase in payments under the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program related to supporting farmers and ranchers impacted by COVID-19.

- Within compensation, the leading contributor to the increase was private wages and salaries.

- The increase in personal dividend income was based primarily on company financial data for the fourth quarter.

Personal current taxes increased $32.8 billion in the fourth quarter after increasing $97.4 billion in the third quarter.

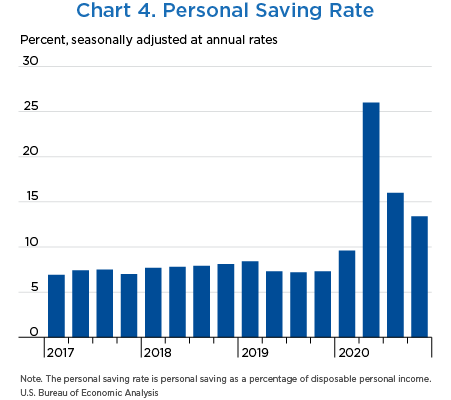

Disposable personal income (DPI) decreased $372.5 billion in the fourth quarter after decreasing $638.9 billion in the third quarter. Personal outlays increased $136.6 billion after increasing $1.30 trillion in the third quarter.

The personal saving rate (chart 4)—personal saving as a percentage of DPI—was 13.4 percent in the fourth quarter; in the third quarter, the personal saving rate was 16.0 percent.

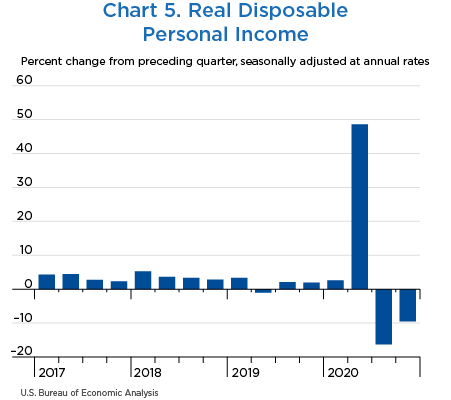

Real DPI (chart 5) decreased 9.5 percent in the fourth quarter after decreasing 16.3 percent in the third quarter. Current-dollar DPI decreased 8.1 percent after decreasing 13.2 percent.

| Line | Series | Level | Change from preceding period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2020 | ||||||

| Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||

| 1 | Personal income | 19,915.8 | 19,576.1 | 190.2 | 1,506.3 | −541.5 | −339.7 |

| 2 | Compensation of employees | 11,537.3 | 11,794.7 | 109.6 | −724.9 | 587.8 | 257.5 |

| 3 | Wages and salaries | 9,409.9 | 9,630.7 | 103.6 | −617.3 | 501.1 | 220.8 |

| 4 | Private industries | 7,967.5 | 8,192.8 | 91.5 | −557.3 | 480.3 | 225.3 |

| 5 | Goods-producing industries | 1,537.0 | 1,569.7 | 1.8 | −112.1 | 106.0 | 32.7 |

| 6 | Manufacturing | 937.5 | 954.8 | −3.6 | −56.0 | 79.7 | 17.2 |

| 7 | Services-producing industries | 6,430.5 | 6,623.1 | 89.8 | −445.2 | 374.3 | 192.6 |

| 8 | Trade, transportation, and utilities | 1,470.1 | 1,496.0 | 17.0 | −82.0 | 108.0 | 25.8 |

| 9 | Other services-producing industries | 4,960.4 | 5,127.1 | 72.8 | −363.2 | 266.3 | 166.8 |

| 10 | Government | 1,442.4 | 1,437.9 | 12.1 | −60.0 | 20.8 | −4.5 |

| 11 | Supplements to wages and salaries | 2,127.4 | 2,164.0 | 6.0 | −107.7 | 86.7 | 36.6 |

| 12 | Proprietors' income with IVA and CCAdj | 1,803.0 | 1,760.4 | 8.3 | −194.1 | 291.1 | −42.6 |

| 13 | Farm | 62.8 | 101.1 | −2.3 | −17.5 | 23.8 | 38.4 |

| 14 | Nonfarm | 1,740.2 | 1,659.3 | 10.6 | −176.6 | 267.2 | −80.9 |

| 15 | Rental income of persons with CCAdj | 804.4 | 807.0 | 6.8 | −6.3 | 8.3 | 2.6 |

| 16 | Personal income receipts on assets | 2,852.3 | 2,897.4 | 3.9 | −74.1 | −57.9 | 45.1 |

| 17 | Personal interest income | 1,619.8 | 1,618.5 | −13.7 | −42.7 | −17.3 | −1.3 |

| 18 | Personal dividend income | 1,232.6 | 1,279.0 | 17.6 | −31.4 | −40.6 | 46.4 |

| 19 | Personal current transfer receipts | 4,369.3 | 3,790.0 | 80.3 | 2,442.5 | −1,308.8 | −579.2 |

| 20 | Government social benefits to persons | 4,323.4 | 3,743.8 | 80.9 | 2,437.8 | −1,304.0 | −579.6 |

| 21 | Social security | 1,080.7 | 1,090.3 | 25.4 | 6.9 | 5.2 | 9.6 |

| 22 | Medicare | 842.7 | 860.6 | 6.7 | 19.4 | 18.7 | 17.9 |

| 23 | Medicaid | 683.7 | 673.6 | 4.7 | 44.7 | 14.9 | −10.1 |

| 24 | Unemployment insurance | 775.2 | 302.4 | 15.5 | 1,041.1 | −309.4 | −472.8 |

| 25 | Veterans' benefits | 145.3 | 148.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 2.9 |

| 26 | Other | 795.8 | 668.7 | 24.4 | 1,322.1 | −1,036.7 | −127.1 |

| 27 | Other current transfer receipts, from business (net) | 45.9 | 46.2 | −0.6 | 4.7 | −4.7 | 0.3 |

| 28 | Less: Contributions for government social insurance | 1,450.4 | 1,473.5 | 18.7 | −63.2 | 62.1 | 23.1 |

| 29 | Less: Personal current taxes | 2,193.9 | 2,226.7 | 31.2 | −155.9 | 97.4 | 32.8 |

| 30 | Equals: Disposable personal income (DPI) | 17,721.9 | 17,349.4 | 159.0 | 1,662.2 | −638.9 | −372.5 |

| 31 | Less: Personal outlays | 14,887.1 | 15,023.8 | −232.5 | −1,513.3 | 1,297.2 | 136.6 |

| 32 | Personal consumption expenditures | 14,401.5 | 14,545.3 | −213.7 | −1,448.1 | 1,304.2 | 143.8 |

| 33 | Personal interest payments1 | 287.2 | 273.5 | −11.7 | −66.9 | 1.2 | −13.7 |

| 34 | Personal current transfer payments | 198.4 | 205.0 | −7.1 | 1.7 | −8.2 | 6.5 |

| 35 | Equals: Personal saving | 2,834.7 | 2,325.6 | 391.5 | 3,175.5 | −1,936.1 | −509.1 |

| 36 | Personal saving as a percentage of DPI | 16.0 | 13.4 | ...... | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| Addenda: | |||||||

| Percent change at annual rate | |||||||

| 37 | Current-dollar DPI | ...... | ...... | 3.9 | 46.2 | −13.2 | −8.1 |

| 38 | Real DPI, chained (2012) dollars | ...... | ...... | 2.6 | 48.6 | −16.3 | −9.5 |

| The effects of selected federal pandemic response programs on personal income (billions of dollars) | |||||||

| In farm proprietors' income with IVA and CCAdj: | |||||||

| 39 | Coronovirus Food Assistance Program2 | 18.5 | 46.3 | ...... | 16.9 | 1.6 | 27.8 |

| 40 | Paycheck Protecton Program loans to businesses3 | 9.2 | 2.8 | ...... | 6.5 | 2.7 | −6.4 |

| In nonfarm proprietors' income with IVA and CCAdj: | |||||||

| 41 | Paycheck Protecton Program loans to businesses3 | 297.1 | 89.3 | ...... | 209.1 | 88.0 | −207.7 |

| In government social benefits to persons, Medicare: | |||||||

| 42 | Increase in Medicare rembursement rates4 | 14.8 | 15.1 | ...... | 9.7 | 5.1 | 0.3 |

| In government social benefits to persons, Unemployment insurance:5 | |||||||

| 43 | Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation | 3.1 | 10.9 | ...... | ...... | 3.1 | 7.8 |

| 44 | Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation | 23.9 | 64.9 | ...... | 7.2 | 16.7 | 41.0 |

| 45 | Pandemic Unemployment Assistance | 156.1 | 112.0 | ...... | 101.5 | 54.6 | −44.1 |

| 46 | Pandemic Unemployment Compensation Payments | 373.1 | 16.1 | ...... | 679.2 | −306.1 | −357.0 |

| In government social benefits to persons, Other: | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||

| 47 | Economic impact payments6 | 15.6 | 5.0 | ...... | 1,078.1 | −1,062.5 | −10.5 |

| 48 | Lost wages supplemental payments7 | 106.2 | 35.9 | ...... | ...... | 106.2 | −70.4 |

| 49 | Paycheck Protecton Program loans to NPISH3 | 27.0 | 10.8 | ...... | 19.1 | 7.9 | −16.2 |

| 50 | Provider Relief Fund to NPISH8 | 58.4 | 34.4 | ...... | 160.9 | −102.5 | −24.0 |

| In personal outlays, personal interest payments: | |||||||

| 51 | Student loan forbearance9 | −36.0 | −36.0 | −7.1 | −28.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

- CCAdj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment

- Consists of nonmortgage interest paid by households. Note that mortgage interest paid by households is an expense item in the calculation of rental income of persons.

- The Coronavirus Food Assistance Program, initially established by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES), provides direct support to farmers and ranchers where prices and market supply chains have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The Paycheck Protection Program, initially established by the CARES Act, provides forgivable loans to help small businesses and nonprofit institutions make payroll and cover other expenses. It also provides funding to reimburse private lending institutions for the costs of administering these loans. For more information, see “How does the Paycheck Protection Program impact the national income and product accounts (NIPAs)?”.

- A two percent reduction in reimbursements paid to Medicare service providers that went into effect in 2013 was initially suspended by the CARES Act. The resulting increased reimbursement rates went into effect beginning on May 1, 2020.

- Unemployment insurance benefits were expanded through several programs that were initially established through the CARES Act. For more information, see “How will the expansion of unemployment benefits in response to the COVID-19 pandemic be recorded in the NIPAs?”.

- Economic impact payments, initially established by the CARES Act, provide direct payments to individuals. For more information, see “How are the economic impact payments to support individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic recorded in the NIPAs?”

- The Federal Emergency Mangement Agency (FEMA) was authorized to make payments from the Disaster Relief Fund to supplement wages lost as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The Department of Health and Human Services distributes money from the Provider Relief Fund to hospitals and health care providers on the front lines of the coronavirus response. This funding supports health care-related expenses or lost revenue attributable to COVID-19 and ensures uninsured Americans can get treatment for COVID-19. In the NIPAs, funds provided to nonprofit hospitals are recorded as social benefits.

- Interest payments due on certain categories of federally-held student loans were initially suspended by the CARES Act. For more information, see “How does the federal response to the COVID-19 affect BEA's estimate of personal interest payments?”.

Real GDP decreased 3.5 percent in 2020 (from the 2019 annual level to the 2020 annual level), compared with an increase of 2.2 percent in 2019 (table 4). The decrease in real GDP in 2020 reflected decreases in consumer spending, exports, private inventory investment, nonresidential fixed investment, and state and local government spending that were partly offset by increases in federal government spending and residential fixed investment. Imports decreased (chart 6).

- The decrease in consumer spending in 2020 was more than accounted for by a decrease in spending on services (led by food services and accommodations, health care, and recreation services).

- The decrease in exports reflected decreases in both services (led by travel) and goods (mainly nonautomotive capital goods).

- The decrease in private inventory investment reflected widespread decreases led by retail trade (mainly motor vehicle dealers) and wholesale trade (mainly durable-goods industries).

- The decrease in nonresidential fixed investment reflected decreases in structures (led by mining exploration, shafts, and wells) and equipment (led by transportation equipment) that were partly offset by an increase in intellectual property products (more than accounted for by software).

- The decrease in state and local government spending reflected a decrease in consumption expenditures (led by compensation).

- The increase in federal government spending reflected increases in both nondefense and defense consumption expenditures. Nondefense consumption expenditures were led by an increase in purchases of intermediate services that supported the processing and administration of Paycheck Protection Program loan applications by banks on behalf of the federal government.

- The increase in residential fixed investment primarily reflected increases in improvements as well as brokers' commissions and other ownership transfer costs.

| Line | Series | Share of current-dollar GDP (percent) | Change from preceding period (percent) | Contribution to percent change in real GDP (percentage points) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product1 | 100.0 | 2.2 | −3.5 | 2.2 | −3.5 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 67.6 | 2.4 | −3.9 | 1.64 | −2.63 |

| 3 | Goods | 22.3 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 0.78 | 0.81 |

| 4 | Durable goods | 7.7 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 0.34 | 0.45 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | 14.5 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 0.44 | 0.36 |

| 6 | Services | 45.3 | 1.8 | −7.3 | 0.86 | −3.44 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 17.2 | 1.7 | −5.3 | 0.30 | −0.94 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 17.6 | 1.9 | −1.8 | 0.32 | −0.31 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 13.3 | 2.9 | −4.0 | 0.39 | −0.54 |

| 10 | Structures | 2.8 | −0.6 | −10.5 | −0.02 | −0.32 |

| 11 | Equipment | 5.6 | 2.1 | −5.0 | 0.12 | −0.29 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 4.9 | 6.4 | 1.5 | 0.29 | 0.07 |

| 13 | Residential | 4.2 | −1.7 | 5.9 | −0.07 | 0.23 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | −0.4 | ...... | ...... | −0.02 | −0.63 |

| 15 | Net exports of goods and services | −3.1 | ...... | ...... | −0.18 | −0.13 |

| 16 | Exports | 10.2 | −0.1 | −13.0 | −0.01 | −1.47 |

| 17 | Goods | 6.8 | −0.1 | −9.5 | −0.01 | −0.69 |

| 18 | Services | 3.4 | −0.1 | −19.2 | −0.01 | −0.78 |

| 19 | Imports | 13.2 | 1.1 | −9.3 | −0.16 | 1.33 |

| 20 | Goods | 11.0 | 0.5 | −6.1 | −0.06 | 0.71 |

| 21 | Services | 2.2 | 3.7 | −22.6 | −0.10 | 0.62 |

| 22 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 18.3 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 0.40 | 0.19 |

| 23 | Federal | 7.1 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 0.26 | 0.29 |

| 24 | National defense | 4.2 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 0.21 | 0.14 |

| 25 | Nondefense | 2.9 | 1.8 | 5.6 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| 26 | State and local | 11.2 | 1.3 | −0.9 | 0.14 | −0.09 |

| Addenda: | ||||||

| 27 | Gross domestic income (GDI)2 | ...... | 1.8 | ...... | ...... | ...... |

| 28 | Average of GDP and GDI | ...... | 2.0 | ...... | ...... | ...... |

- The GDP estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

- GDI is deflated by the implicit price deflator for GDP. Not estimated with the Q4 advance or second estimates.

- “Real” estimates are in chained (2012) dollars, and price indexes are chain-type measures. Each GDP estimate for a quarter (advance, second, and third) incorporates increasingly comprehensive and improved source data; for more information, see “The Revisions to GDP, GDI, and Their Major Components” in the January 2018 Survey of Current Business. Quarterly estimates are expressed at seasonally adjusted annual rates, which reflect a rate of activity for a quarter as if it were maintained for a year.

- In this article, “consumer spending” refers to “personal consumption expenditures,” “inventory investment” refers to “change in private inventories,” and “government spending” refers to “government consumption expenditures and gross investment.”