GDP and the Economy

Third Estimates for the First Quarter of 2022

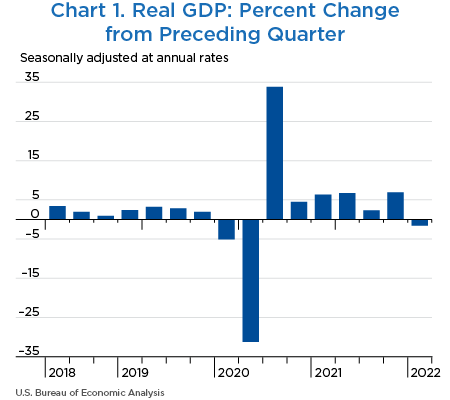

Real gross domestic product (GDP) decreased at an annual rate of 1.6 percent in the first quarter of 2022, according to the third estimates of the National Income and Product Accounts (chart 1 and table 1).1 With the third estimate, real GDP growth was revised down 0.1 percentage point from the second estimate issued last month. In the fourth quarter of 2021, real GDP increased 6.9 percent.

The decline in real GDP in the first quarter of 2022 occurred amid a resurgence of COVID–19 cases from the Omicron variant and decreases in government pandemic assistance payments. Other economic conditions including supply-chain challenges, low unemployment, and widespread inflation continued in the first quarter. The full economic effects of the COVID–19 pandemic and other economic factors cannot be quantified in the GDP estimates, because the impacts are generally embedded in source data and cannot be separately identified. Real GDP for the first quarter of 2022 is 2.7 percent above the level of real GDP for the fourth quarter of 2019, the most recent quarter prior to the onset of the COVID–19 pandemic. For more information, refer to the “Technical Note” and “Federal Recovery Programs and BEA Statistics.”

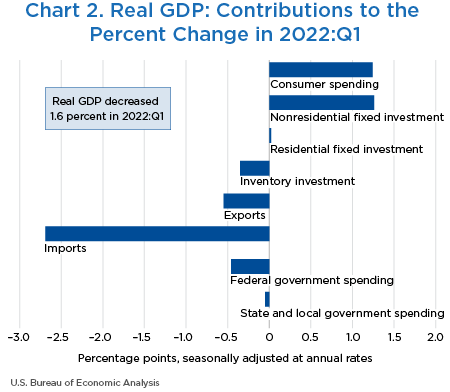

Real GDP decreased 1.6 percent (annual rate) in the first quarter, following an increase of 6.9 percent in the fourth quarter. The decrease in real GDP reflected decreases in exports, federal government spending, private inventory investment, and state and local government spending, while imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased. Nonresidential fixed investment, consumer spending, and residential fixed investment increased (chart 2 and table 1).2

- Within exports, a decrease in goods was partly offset by an increase in services.

- The decrease in goods was led by nonfood and nonautomotive consumer goods (mainly nondurable goods such as medicinal, dental, and pharmaceutical preparations), industrial supplies and materials (mainly petroleum and products), and foods, feeds, and beverages (mainly soybeans).

- The increase in services largely reflected increases in government goods and services (not elsewhere classified) and in travel that were partly offset by charges for the use of intellectual property and other business services (led by financial services).

- The decrease in federal government spending was led by defense spending on intermediate goods and services, led by services.

- The decrease in private inventory investment mainly reflected decreases in wholesale trade (mainly motor vehicles) and in mining, utilities, and construction (more than accounted for by utilities) that were partly offset by an increase in manufacturing.

- The decrease in state and local government spending reflected a decrease in investment in structures that was partly offset by an increase in spending on intermediate goods and services.

- Within imports, the increase primarily reflected an increase in goods, led by nonfood and nonautomotive consumer goods, nonautomotive capital goods, and automotive vehicles, engines, and parts.

- The increase in nonresidential fixed investment reflected increases in equipment and intellectual property products that was partly offset by a decrease in structures.

- Within equipment, the leading contributors to the increase were information processing equipment (led by computers and peripheral equipment and by communications equipment), other equipment (mainly furniture and fixtures), and industrial equipment (notably, special industry machinery).

- The increase in intellectual property products primarily reflected increases in software (notably, prepackaged software) and in research and development.

- The increase in consumer spending reflected an increase in services that was partly offset by a decrease in spending on goods.

- Within services, increases were widespread; housing and utilities (mainly electricity and gas) and other services (led by communication) were the leading contributors.

- Within goods, a decrease in nondurable goods, led by gasoline and other energy goods and by food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption (groceries), was partly offset by an increase in durable goods, led by motor vehicles and parts (mainly spending on new light trucks).

- The increase in residential fixed investment primarily reflected an increase in single-family structures that was partly offset by a decrease in brokers' commissions and other ownership transfer costs.

Real gross domestic income (GDI), the sum of incomes earned and costs incurred in the production of GDP, increased 1.8 percent in the first quarter, compared with an increase of 6.3 percent in the fourth quarter. The average of real GDP and real GDI, a supplemental measure of U.S. economic activity that equally weights GDP and GDI, increased 0.1 percent in the first quarter, compared with an increase of 6.6 percent in the fourth quarter.

| Line | Series | Share of current-dollar GDP (percent) | Change from preceding period (percent) | Contribution to percent change in real GDP (percentage points) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product (GDP)1 | 100.0 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 6.9 | −1.6 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 6.9 | −1.6 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 68.4 | 12.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 7.92 | 1.35 | 1.76 | 1.24 |

| 3 | Goods | 23.8 | 13.0 | −8.8 | 1.1 | −0.3 | 2.99 | −2.21 | 0.28 | −0.07 |

| 4 | Durable goods | 8.7 | 11.6 | −24.6 | 2.5 | 5.9 | 1.01 | −2.52 | 0.22 | 0.49 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | 15.1 | 13.9 | 2.0 | 0.4 | −3.7 | 1.98 | 0.30 | 0.06 | −0.56 |

| 6 | Services | 44.5 | 11.5 | 8.2 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 4.93 | 3.57 | 1.48 | 1.31 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 19.3 | −3.9 | 12.4 | 36.7 | 5.0 | −0.65 | 2.05 | 5.82 | 0.93 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 18.3 | 3.3 | −0.9 | 2.7 | 7.4 | 0.61 | −0.16 | 0.50 | 1.28 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 13.5 | 9.2 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 10.0 | 1.21 | 0.22 | 0.40 | 1.26 |

| 10 | Structures | 2.6 | −3.0 | −4.1 | −8.3 | −0.9 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.22 | −0.02 |

| 11 | Equipment | 5.6 | 12.1 | −2.3 | 2.8 | 14.1 | 0.66 | −0.13 | 0.17 | 0.73 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 5.3 | 12.5 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 11.2 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.56 |

| 13 | Residential | 4.8 | −11.7 | −7.7 | 2.2 | 0.4 | −0.60 | −0.38 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | 1.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | −1.26 | 2.20 | 5.32 | −0.35 |

| 15 | Net exports of goods and services | −4.8 | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.18 | −1.26 | −0.23 | −3.23 |

| 16 | Exports | 11.2 | 7.6 | −5.3 | 22.4 | −4.8 | 0.80 | −0.59 | 2.24 | −0.55 |

| 17 | Goods | 7.9 | 6.4 | −5.0 | 23.4 | −7.6 | 0.48 | −0.39 | 1.64 | −0.63 |

| 18 | Services | 3.3 | 10.4 | −5.9 | 19.9 | 2.4 | 0.32 | −0.19 | 0.59 | 0.08 |

| 19 | Imports | 16.0 | 7.1 | 4.7 | 17.9 | 18.9 | −0.99 | −0.68 | −2.46 | −2.69 |

| 20 | Goods | 13.5 | 4.3 | −0.3 | 18.9 | 20.2 | −0.51 | 0.04 | −2.16 | −2.40 |

| 21 | Services | 2.6 | 23.6 | 35.0 | 13.1 | 12.1 | −0.48 | −0.72 | −0.31 | −0.29 |

| 22 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 17.2 | −2.0 | 0.9 | −2.6 | −2.9 | −0.36 | 0.17 | −0.46 | −0.51 |

| 23 | Federal | 6.4 | −5.3 | −5.1 | −4.3 | −6.8 | −0.38 | −0.35 | −0.29 | −0.46 |

| 24 | National defense | 3.7 | −1.1 | −1.7 | −6.0 | −9.9 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.24 | −0.39 |

| 25 | Nondefense | 2.7 | −10.7 | −9.5 | −2.0 | −2.5 | −0.34 | −0.29 | −0.05 | −0.07 |

| 26 | State and local | 10.8 | 0.2 | 4.9 | −1.6 | −0.5 | 0.02 | 0.52 | −0.17 | −0.05 |

| Addenda: | ||||||||||

| 27 | Gross domestic income (GDI)2 | --- | 4.3 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 1.8 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 28 | Average of GDP and GDI | --- | 5.5 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 0.1 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 29 | Final sales of domestic product | --- | 8.1 | 0.1 | 1.5 | −1.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 30 | Goods | 32.1 | 9.8 | 0.1 | 19.0 | −6.6 | 3.05 | 0.05 | 5.70 | −2.18 |

| 31 | Services | 59.1 | 7.9 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 4.62 | 2.77 | 1.44 | 0.83 |

| 32 | Structures | 8.8 | −10.0 | −5.8 | −2.9 | −2.5 | −0.94 | −0.52 | −0.25 | −0.22 |

- The GDP estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

- GDI is deflated by the implicit price deflator for GDP.

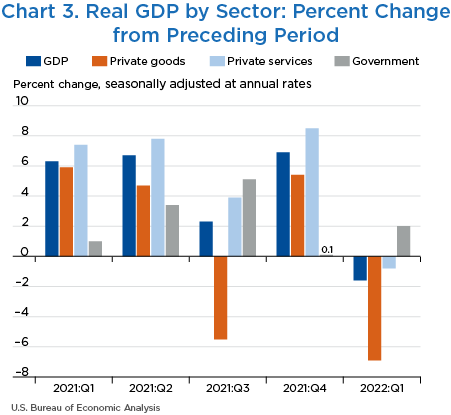

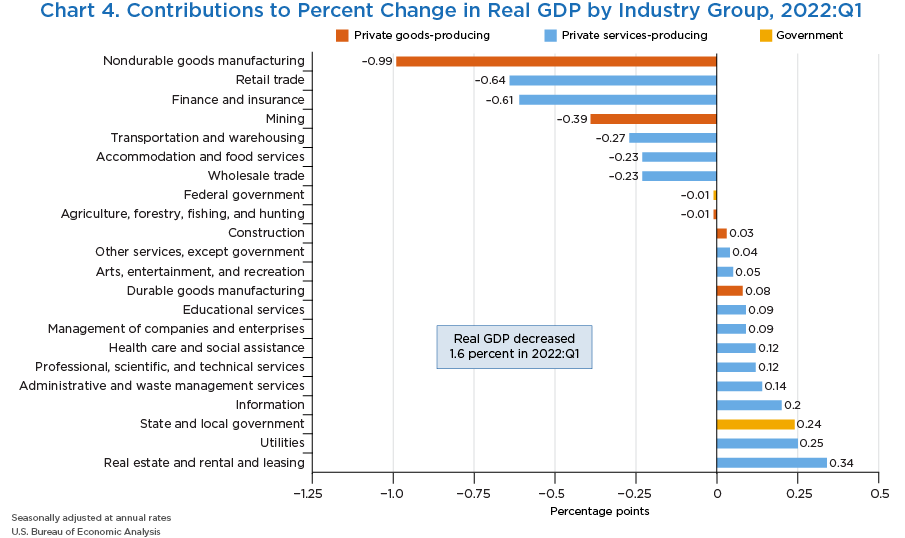

The third estimate of GDP includes estimates of GDP by industry, or value added—a measure of an industry’s contribution to GDP. In the first quarter, private goods-producing industries decreased 6.9 percent, private services-producing industries decreased 0.8 percent, and government increased 2.0 percent (chart 3 and table 2). Overall, 9 of 22 industry groups contributed to the first-quarter decline in real GDP (chart 4).

- Within private goods-producing industries, the leading contributors to the decrease were nondurable goods manufacturing (led by petroleum and coal products) and mining.

- Within private services-producing industries, the leading contributors to the decrease were retail trade and finance and insurance; these were partly offset by an increase in real estate and rental and leasing.

- The increase in government reflected an increase in state and local government that was partly offset by a decrease in federal government.

| Line | Series | Share of current-dollar GDP (percent) | Change from preceding period (percent) | Contribution to percent change in real GDP (percentage points) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product (GDP)1 | 100.0 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 6.9 | −1.6 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 6.9 | −1.6 |

| 2 | Private industries | 88.2 | 7.1 | 1.9 | 7.9 | −2.1 | 6.26 | 1.70 | 6.90 | −1.83 |

| 3 | Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | 1.2 | −13.1 | −9.0 | 2.4 | −1.3 | −0.14 | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| 4 | Mining | 1.5 | 7.3 | −7.9 | 12.0 | −23.9 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.15 | −0.39 |

| 5 | Utilities | 1.6 | 3.8 | −16.1 | −8.6 | 16.1 | 0.06 | −0.29 | −0.15 | 0.25 |

| 6 | Construction | 4.1 | 6.6 | −13.9 | −9.4 | 0.7 | 0.28 | −0.62 | −0.40 | 0.03 |

| 7 | Manufacturing | 11.4 | 5.5 | −1.5 | 10.9 | −7.7 | 0.63 | −0.17 | 1.20 | −0.91 |

| 8 | Durable goods | 6.0 | 4.3 | −2.5 | 9.7 | 1.2 | 0.27 | −0.15 | 0.58 | 0.08 |

| 9 | Nondurable Goods | 5.3 | 7.0 | −0.4 | 12.2 | −17.0 | 0.35 | −0.02 | 0.62 | −0.99 |

| 10 | Wholesale trade | 6.1 | 3.7 | −8.1 | 9.4 | −3.8 | 0.23 | −0.51 | 0.55 | −0.23 |

| 11 | Retail trade | 6.0 | −14.7 | −14.0 | 7.6 | −10.2 | −0.97 | −0.91 | 0.46 | −0.64 |

| 12 | Transporation and warehousing | 3.0 | −9.7 | 12.2 | 8.8 | −8.8 | −0.27 | 0.32 | 0.25 | −0.27 |

| 13 | Information | 5.6 | 25.2 | 8.0 | 20.1 | 3.6 | 1.30 | 0.44 | 1.06 | 0.20 |

| 14 | Finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing | 20.7 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 5.9 | −1.3 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1.24 | −0.27 |

| 15 | Finance and insurance | 8.1 | 3.4 | 7.8 | 4.1 | −7.1 | 0.30 | 0.64 | 0.35 | −0.61 |

| 16 | Real estate and rental and leasing | 12.6 | 4.9 | 2.2 | 7.1 | 2.7 | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.89 | 0.34 |

| 17 | Professional and business services | 13.0 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 12.1 | 2.8 | 1.48 | 1.54 | 1.52 | 0.36 |

| 18 | Professional, scientific, and technical services | 7.8 | 15.3 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 1.6 | 1.13 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.12 |

| 19 | Management of companies and enterprises | 1.8 | 2.2 | 7.9 | 0.9 | 5.2 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.09 |

| 20 | Administrative and waste management services | 3.4 | 9.7 | 16.0 | 18.6 | 4.2 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.14 |

| 21 | Educational services, health care, and social assistance | 8.3 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 7.2 | 2.6 | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.21 |

| 22 | Educational services | 1.1 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 4.4 | 8.7 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| 23 | Health care and social assistance | 7.1 | 5.7 | 2.6 | 7.7 | 1.7 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.55 | 0.12 |

| 24 | Arts, entertainment, recreation, accomodation, and food services | 3.9 | 68.4 | 23.6 | 7.7 | −4.7 | 1.83 | 0.79 | 0.29 | −0.18 |

| 25 | Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 0.9 | 16.0 | 43.1 | 24.1 | 5.4 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.05 |

| 26 | Accommodation and food services | 2.9 | 88.7 | 18.4 | 3.1 | −7.6 | 1.70 | 0.49 | 0.09 | −0.23 |

| 27 | Other services, except government | 2.0 | 17.5 | 6.4 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| 28 | Government | 11.8 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| 29 | Federal | 3.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | −1.2 | −0.3 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| 30 | State and local | 8.1 | 4.8 | 7.4 | 0.7 | 3.0 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.24 |

| Addenda: | ||||||||||

| 31 | Private goods-producing industries2 | 18.2 | 4.7 | −5.5 | 5.4 | −6.9 | 0.84 | −1.00 | 0.98 | −1.29 |

| 32 | Private services-producing industries3 | 70.0 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 8.5 | −0.8 | 5.42 | 2.70 | 5.91 | −0.54 |

- The GDP estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

- Consists of agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting; mining; construction; and manufacturing.

- Consists of utilities; wholesale trade; retail trade; transportation and warehousing; information; finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing; professional and business services; educational services, health care, and social assistance; arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, and food services; and other services, except government.

Note. Percent changes are from these GDP by industry tables: “Value Added by Industry as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product,” “Percent Changes in Chain-Type Quantity Indexes for Value Added by Industry,” and “Contributions to Percent Change in Real Gross Domestic Product by Industry.”

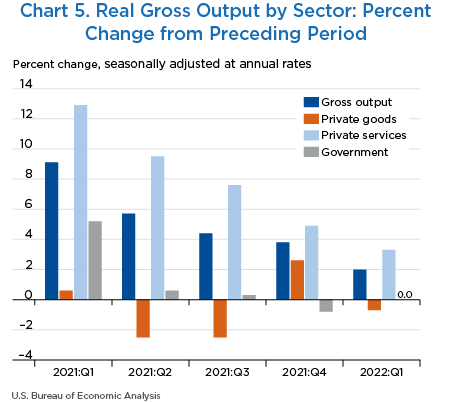

Real gross output—principally a measure of an industry's sales or receipts, which includes sales to final users in the economy (GDP) and sales to other industries (intermediate inputs)—increased 2.0 percent in the first quarter (chart 5 and table 3). Private services-producing industries increased 3.3 percent, private goods-producing industries decreased 0.7 percent, and government increased less than 0.1 percent. Overall, 15 of 22 industry groups contributed to the increase in real gross output.

| Line | Series | Change from preceding period (percent) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | ||||

| Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | ||

| 1 | All industries | 5.7 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 2.0 |

| 2 | Private industries | 6.3 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 2.2 |

| 3 | Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | −4.1 | −3.6 | −1.1 | −1.2 |

| 4 | Mining | 13.7 | −0.1 | 6.6 | 4.8 |

| 5 | Utilities | 6.9 | −0.9 | −6.9 | 3.9 |

| 6 | Construction | −8.3 | −8.2 | −6.5 | −3.2 |

| 7 | Manufacturing | −1.7 | −0.9 | 5.4 | −0.4 |

| 8 | Durable goods | −2.1 | −1.7 | 8.2 | 2.9 |

| 9 | Nondurable goods | −1.3 | −0.2 | 2.7 | −3.6 |

| 10 | Wholesale trade | 9.7 | 0.2 | 8.7 | 13.1 |

| 11 | Retail trade | −4.4 | −11.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 |

| 12 | Transporation and warehousing | 4.3 | 19.7 | 15.1 | −0.8 |

| 13 | Information | 19.4 | 12.6 | 9.4 | 11.2 |

| 14 | Finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing | 1.5 | 6.7 | 2.5 | 0.6 |

| 15 | Finance and insurance | −1.2 | 10.2 | −0.4 | −3.1 |

| 16 | Real estate and rental and leasing | 3.7 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 3.8 |

| 17 | Professional and business services | 9.2 | 13.1 | 7.4 | 6.1 |

| 18 | Professional, scientific, and technical services | 9.4 | 11.3 | 6.5 | 5.7 |

| 19 | Management of companies and enterprises | −0.5 | 9.2 | −4.2 | 4.2 |

| 20 | Administrative and waste management services | 14.3 | 19.0 | 15.6 | 8.0 |

| 21 | Educational services, health care, and social assistance | 9.9 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 1.2 |

| 22 | Educational services | 15.4 | 6.7 | 4.6 | 5.7 |

| 23 | Health care and social assistance | 9.2 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.6 |

| 24 | Arts, entertainment, recreation, accomodation, and food services | 81.4 | 36.9 | 0.8 | −4.4 |

| 25 | Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 25.3 | 64.8 | 9.0 | 4.5 |

| 26 | Accommodation and food services | 99.8 | 30.6 | −1.2 | −6.6 |

| 27 | Other services, except government | 20.1 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| 28 | Government | 0.6 | 0.3 | −0.8 | 0.0 |

| 29 | Federal | −6.4 | −8.1 | −3.5 | −5.3 |

| 30 | State and local | 4.1 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 2.4 |

| Addenda: | |||||

| 31 | Private goods-producing industries1 | −2.5 | −2.5 | 2.6 | −0.7 |

| 32 | Private services-producing industries2 | 9.5 | 7.6 | 4.9 | 3.3 |

- Consists of agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting; mining; construction; and manufacturing.

- Consists of utilities; wholesale trade; retail trade; transportation and warehousing; information; finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing; professional and business services; educational services, health care, and social assistance; arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, and food services; and other services, except government.

Note. Percent changes are from the table Percent Changes in Chain-Type Quantity Indexes for Gross Output by Industry which is available through BEA's Interactive Data Application.

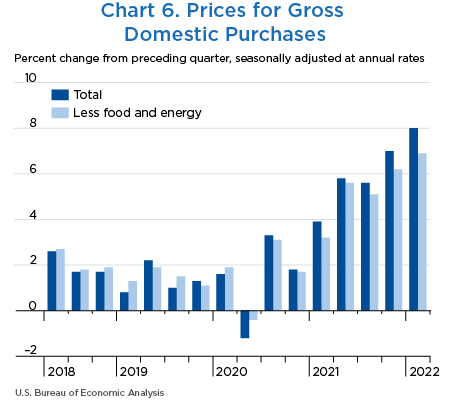

The Bureau of Economic Analysis' (BEA's) featured measure of inflation in the U.S. economy, the price index for gross domestic purchases (goods and services purchased by U.S. residents), increased 8.0 percent in the first quarter after increasing 7.0 percent in the fourth quarter (table 4 and chart 6). Price increases were widespread across all major expenditure categories and were led by increases in consumer goods and services:

- Within consumer goods, the leading contributors to the price increase were gasoline and other energy goods, groceries, other nondurable goods (led by prescription drugs and household supplies), and furnishings and durable household equipment.

- Within consumer services, the leading contributor was an increase in prices paid for housing and utilities (mainly reflecting imputed rental of owner-occupied nonfarm housing) and health care (notably, hospital services).

Food prices increased 11.2 percent in the first quarter after increasing 9.0 percent in the fourth quarter. Prices for energy goods and services increased 43.2 percent after increasing 34.0 percent. Gross domestic purchases prices excluding food and energy increased 6.9 percent after increasing 6.2 percent.

Consumer prices excluding food and energy, a measure of the “core” rate of inflation, increased 5.2 percent in the first quarter after increasing 5.0 percent in the fourth quarter.

| Line | Series | Change from preceding period (percent) | Contribution to percent change in gross domestic purchases prices (percentage points) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||||

| Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic purchases1 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 7.0 | 8.0 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 6.5 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 4.23 | 3.54 | 4.19 | 4.63 |

| 3 | Goods | 9.3 | 7.3 | 10.2 | 11.8 | 2.11 | 1.67 | 2.27 | 2.62 |

| 4 | Durable goods | 16.8 | 9.7 | 10.8 | 6.5 | 1.38 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.54 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | 5.0 | 5.9 | 9.8 | 15.0 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 1.39 | 2.07 |

| 6 | Services | 5.0 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 2.12 | 1.87 | 1.92 | 2.02 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 2.9 | 6.1 | 8.8 | 9.9 | 0.52 | 1.03 | 1.53 | 1.78 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 4.5 | 7.0 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 0.80 | 1.20 | 1.51 | 1.68 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 0.9 | 4.3 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 0.13 | 0.56 | 0.99 | 0.89 |

| 10 | Structures | 8.9 | 11.1 | 24.4 | 18.2 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.54 | 0.42 |

| 11 | Equipment | −3.2 | 4.6 | 6.9 | 7.1 | −0.16 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.38 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| 13 | Residential | 15.3 | 14.8 | 11.9 | 18.2 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.78 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.28 | −0.17 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| 15 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 6.1 | 6.1 | 7.6 | 9.8 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.27 | 1.60 |

| 16 | Federal | 4.1 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.47 |

| 17 | National defense | 4.3 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 8.4 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.30 |

| 18 | Nondefense | 3.9 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| 19 | State and local | 7.3 | 6.7 | 8.9 | 11.2 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.91 | 1.13 |

| Addenda: | |||||||||

| Gross domestic purchases: | |||||||||

| 20 | Food | 1.6 | 7.9 | 9.0 | 11.2 | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.56 |

| 21 | Energy goods and services | 21.2 | 19.4 | 34.0 | 43.2 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.82 | 1.07 |

| 22 | Excluding food and energy | 5.6 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 5.20 | 4.72 | 5.72 | 6.38 |

| Personal consumption expenditures: | |||||||||

| 23 | Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | 4.1 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 11.4 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 24 | Energy goods and services | 20.4 | 18.9 | 34.2 | 42.8 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 25 | Excluding food and energy | 6.1 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 5.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 26 | Gross domestic product | 6.1 | 6.0 | 7.1 | 8.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 27 | Exports of goods and services | 19.4 | 9.7 | 6.4 | 18.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 28 | Imports of goods and services | 13.4 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 13.8 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

- The estimated prices for gross domestic purchases under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

First-quarter real GDP was revised down 0.1 percentage point from the “second” estimate, primarily reflecting downward revisions to consumer spending and federal government spending that were mostly offset by upward revisions to private inventory investment, nonresidential fixed investment, and exports (table 5). Imports were revised up.

- Within consumer spending, both services and goods were revised down.

- For services, revisions primarily reflected downward revisions to financial services and insurance (notably, banking and other financial services) and health care (notably, hospitals).

- For goods, a downward revision to durable goods (led by recreational goods and vehicles) was partly offset by an upward revision to nondurable goods (more than accounted for by gasoline and other energy goods).

- The downward revision to federal government spending primarily reflected a downward revision to national defense equipment investment.

- The revision to private inventory investment reflected an upward revision to nonfarm inventories, led by retail trade (notably, general merchandise stores) and “other” industries (specifically, information).

- Within nonresidential fixed investment, the upward revision was led by structures (mainly commercial and health care).

- The upward revisions to both exports and imports were based primarily on revised U.S. Census Bureau goods data as well as the annual revision of BEA's International Transactions Accounts, which was incorporated on a best-change basis. Within exports, the leading contributor to the upward revision was goods (led by other goods and nonautomotive capital goods). Within imports, an upward revision to services (led by transport) was partly offset by a downward revision to goods (led by nonfood and nonautomotive consumer goods).

| Line | Series | Change from preceding period (percent) | Contribution to percent change in real GDP (percentage points) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second estimate | Third estimate | Third estimate minus second estimate | Second estimate | Third estimate | Third estimate minus second estimate | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product (GDP)1 | −1.5 | −1.6 | −0.1 | −1.5 | −1.6 | −0.1 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 3.1 | 1.8 | −1.3 | 2.09 | 1.24 | −0.85 |

| 3 | Goods | 0.0 | −0.3 | −0.3 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.07 |

| 4 | Durable goods | 6.8 | 5.9 | −0.9 | 0.57 | 0.49 | −0.08 |

| 5 | Nondurable goods | −3.7 | −3.7 | 0.0 | −0.57 | −0.56 | 0.01 |

| 6 | Services | 4.8 | 3.0 | −1.8 | 2.09 | 1.31 | −0.78 |

| 7 | Gross private domestic investment | 0.5 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 0.10 | 0.93 | 0.83 |

| 8 | Fixed investment | 6.8 | 7.4 | 0.6 | 1.18 | 1.28 | 0.10 |

| 9 | Nonresidential | 9.2 | 10.0 | 0.8 | 1.16 | 1.26 | 0.10 |

| 10 | Structures | −3.6 | −0.9 | 2.7 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| 11 | Equipment | 13.2 | 14.1 | 0.9 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.05 |

| 12 | Intellectual property products | 11.6 | 11.2 | −0.4 | 0.57 | 0.56 | −0.01 |

| 13 | Residential | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 14 | Change in private inventories | .... | .... | .... | −1.09 | −0.35 | 0.74 |

| 15 | Net exports of goods and services | .... | .... | .... | −3.23 | −3.23 | 0.00 |

| 16 | Exports | −5.4 | −4.8 | 0.6 | −0.62 | −0.55 | 0.07 |

| 17 | Goods | −8.9 | −7.6 | 1.3 | −0.73 | −0.63 | 0.10 |

| 18 | Services | 3.6 | 2.4 | −1.2 | 0.11 | 0.08 | −0.03 |

| 19 | Imports | 18.3 | 18.9 | 0.6 | −2.61 | −2.69 | −0.08 |

| 20 | Goods | 20.9 | 20.2 | −0.7 | −2.48 | −2.40 | 0.08 |

| 21 | Services | 5.4 | 12.1 | 6.7 | −0.13 | −0.29 | −0.16 |

| 22 | Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | −2.7 | −2.9 | −0.2 | −0.47 | −0.51 | −0.04 |

| 23 | Federal | −6.1 | −6.8 | −0.7 | −0.40 | −0.46 | −0.06 |

| 24 | National defense | −8.5 | −9.9 | −1.4 | −0.33 | −0.39 | −0.06 |

| 25 | Nondefense | −2.6 | −2.5 | 0.1 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.00 |

| 26 | State and local | −0.6 | −0.5 | 0.1 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| Addenda: | |||||||

| 27 | Final sales of domestic product | −0.4 | −1.2 | −0.8 | --- | --- | --- |

| 28 | Gross domestic income (GDI)2 | 2.1 | 1.8 | −0.3 | --- | --- | --- |

| 29 | Average of GDP and GDI | 0.3 | 0.1 | −0.2 | --- | --- | --- |

| 30 | Gross domestic purchases price index | 8.0 | 8.0 | 0.0 | --- | --- | --- |

| 31 | GDP price index | 8.1 | 8.2 | 0.1 | --- | --- | --- |

- The GDP estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

- GDI is deflated by the implicit price deflator for GDP.

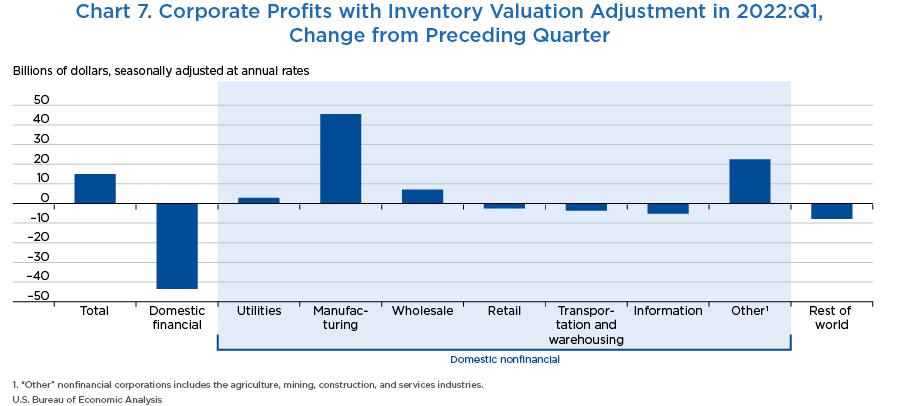

Measured in current dollars, profits from current production (corporate profits with the inventory valuation adjustment (IVA) and the capital consumption adjustment (CCAdj)) decreased $63.8 billion, or 2.2 percent at a quarterly rate, in the first quarter after increasing $20.4 billion, or 0.7 percent, in the fourth quarter (table 6). Profits of domestic financial corporations decreased $51.1 billion, profits of domestic nonfinancial corporations decreased $4.8 billion, and rest-of-the-world profits decreased $7.9 billion.

| Line | Series | Billions of dollars (annual rate) | Percent change from preceding quarter (quarterly rate) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Change from preceding quarter | |||||||||

| 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | ||

| Current production measures: | ||||||||||

| 1 | Corporate profits with IVA and CCAdj | 2,872.7 | 267.8 | 96.9 | 20.4 | −63.8 | 10.5 | 3.4 | 0.7 | −2.2 |

| 2 | Domestic industries | 2,352.6 | 274.0 | 45.8 | 3.7 | −55.9 | 13.1 | 1.9 | 0.2 | −2.3 |

| 3 | Financial | 499.5 | 52.8 | 14.2 | −1.3 | −51.1 | 10.9 | 2.6 | −0.2 | −9.3 |

| 4 | Nonfinancial | 1,853.0 | 221.3 | 31.6 | 5.0 | −4.8 | 13.8 | 1.7 | 0.3 | −0.3 |

| 5 | Rest of the world | 520.1 | −6.2 | 51.1 | 16.8 | −7.9 | −1.3 | 11.1 | 3.3 | −1.5 |

| 6 | Receipts from the rest of the world | 988.2 | 27.4 | 65.2 | 12.6 | 17.7 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| 7 | Less: Payments to the rest of the world | 468.1 | 33.6 | 14.1 | −4.1 | 25.6 | 8.4 | 3.3 | −0.9 | 5.8 |

| 9 | Less: Taxes on corporate income | 469.8 | 34.9 | 14.7 | 15.8 | 60.7 | 10.1 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 14.8 |

| 10 | Equals: Profits after tax | 2,402.9 | 232.9 | 82.1 | 4.7 | −124.5 | 10.5 | 3.4 | 0.2 | −4.9 |

| 11 | Net dividends | 1,476.5 | 51.4 | 27.7 | 26.4 | 11.4 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.8 |

| 12 | Undistributed profits from current production | 926.4 | 181.5 | 54.5 | −21.8 | −135.9 | 21.4 | 5.3 | −2.0 | −12.8 |

| 13 | Net cash flow with IVA | 3,158.5 | 224.7 | 56.5 | 95.3 | −71.9 | 7.9 | 1.8 | 3.0 | −2.2 |

- CCAdj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment

Industry profits (corporate profits by industry with IVA) increased $14.9 billion, or 0.5 percent at a quarterly rate, in the first quarter after increasing $57.7 billion, or 0.9 percent, in the fourth quarter (table 7 and chart 7). Domestic profits increased $22.8 billion in the first quarter and primarily reflected increases in manufacturing and “other” nonfinancial industries that were partly offset by a decrease in profits for financial industries.

Profits after tax (without IVA and CCAdj)—BEA's profits measure that is conceptually most like the profits for companies in the Standard & Poor's 500 Index—increased $26.4 billion in the first quarter.

| Line | Series | Billions of dollars (annual rate) | Percent change from preceding quarter (quarterly rate) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Change from preceding quarter | |||||||||

| 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | ||

| Industry profits: | ||||||||||

| 1 | Corporate profits with IVA | 2,946.5 | 285.9 | 126.1 | 57.7 | 14.9 | 11.6 | 4.6 | 2.0 | 0.5 |

| 2 | Domestic industries | 2,426.4 | 292.1 | 75.0 | 40.9 | 22.8 | 14.6 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 0.9 |

| 3 | Financial | 558.8 | 57.0 | 20.6 | 4.9 | −43.5 | 11.0 | 3.6 | 0.8 | −7.2 |

| 4 | Nonfinancial | 1,867.6 | 235.1 | 54.4 | 36.1 | 66.4 | 15.9 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 3.7 |

| 5 | Utilities | 22.8 | −9.1 | 8.5 | −0.5 | 2.9 | −43.4 | 71.8 | −2.2 | 14.3 |

| 6 | Manufacturing | 601.2 | 48.6 | 49.9 | 55.3 | 45.5 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 8.2 |

| 7 | Wholesale trade | 167.4 | 25.0 | 17.8 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 22.2 | 12.9 | 3.2 | 4.4 |

| 8 | Retail trade | 266.5 | 27.4 | −37.4 | −1.2 | −2.5 | 9.8 | −12.1 | −0.4 | −0.9 |

| 9 | Transportation and warehousing | 43.0 | 29.8 | −17.0 | −0.8 | −3.6 | 86.4 | −26.3 | −1.6 | −7.8 |

| 10 | Information | 167.2 | 14.5 | 1.3 | −4.4 | −5.2 | 9.0 | 0.7 | −2.5 | −3.0 |

| 11 | Other nonfinancial | 599.5 | 98.8 | 31.3 | −17.4 | 22.4 | 21.3 | 5.6 | −2.9 | 3.9 |

| 12 | Rest of the world | 520.1 | −6.2 | 51.1 | 16.8 | −7.9 | −1.3 | 11.1 | 3.3 | −1.5 |

| Addenda: | ||||||||||

| 13 | Profits before tax (without IVA and CCAdj) | 3,196.5 | 357.7 | 45.9 | −5.5 | 87.1 | 13.2 | 1.5 | −0.2 | 2.8 |

| 14 | Profits after tax (without IVA and CCAdj) | 2,726.7 | 322.8 | 31.2 | −21.3 | 26.4 | 13.6 | 1.2 | −0.8 | 1.0 |

| 15 | IVA | −250.0 | −71.8 | 80.2 | 63.2 | −72.2 | ........... | ........... | ........... | ........... |

| 16 | CCAdj | −73.8 | −18.1 | −29.2 | −37.2 | −78.8 | ........... | ........... | ........... | ........... |

- CCAdj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment