The 2020 Annual Update of the National Income and Product Accounts

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released its annual update of the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) on July 30. For real gross domestic product (GDP) and most major components, the updates covered the most recent 5 years (2015–2019) and the first quarter of 2020; for selected estimates of income and saving, the update extended to previous years.1 The reference year for price and quantity estimates remains 2012.

As is usual for NIPA annual updates, the revised estimates reflect newly available source data that are more complete, more detailed, and otherwise more reliable than those that were previously incorporated.

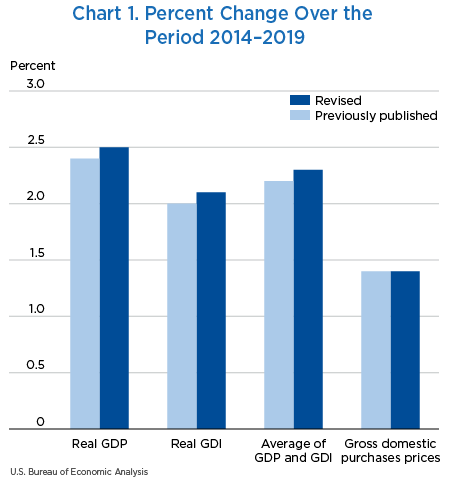

With this update, economic growth from 2014 to 2019 is revised up slightly, but the revised estimates are similar to the previously published estimates (chart 1):

- Real GDP—an inflation-adjusted measure of the value of the goods and services produced by the nation's economy less the value of the goods and services used up in production—increased at an average annual rate of 2.5 percent; in the previously published estimates, real GDP increased 2.4 percent.

- Real gross domestic income (GDI)—which measures the value of the production of goods and services in the United States as the incomes earned and the costs incurred in production—increased at an average annual rate of 2.1 percent; in the previously published estimates, real GDI increased at an average annual rate of 2.0 percent.

- The average of real GDP and real GDI increased at an average annual rate of 2.3 percent; in the previously published estimates, the measure increased at an average annual rate of 2.2 percent.

- The price index for gross domestic purchases increased at an average annual rate of 1.4 percent, unrevised from the previously published estimates.

- Contributors to real GDP growth for 2015–2019 are little changed from the earlier estimates. Consumer spending remains the driving force behind the growth in GDP in all years. Revised estimates show that the contribution of private investment was stronger in 2018 than previously shown, while the contribution of consumer spending was weaker. In 2019, the contribution of fixed investment was stronger than previously shown, while the contributions of inventory investment and consumer spending were weaker.

- For the period of expansion from the second quarter of 2009 through the fourth quarter of 2019, real GDP increased at an average annual rate of 2.3 percent, unrevised from the previously published estimate. The rate of growth in real GDI over this period was also unrevised at 2.4 percent.

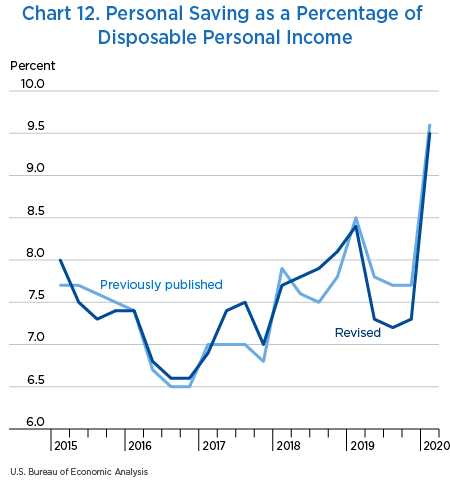

- The personal saving rate (personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income) was revised down 0.1 percentage point to 7.5 percent for 2015 and up 0.1 percentage point to 6.9 percent for 2016. It was revised up 0.2 percentage point for 2017 and for 2018 to 7.2 percent and 7.8 percent, respectively. The largest revision was for 2019; it was revised down from 7.9 percent to 7.5 percent.

The updated NIPA estimates reflect the incorporation of newly available and revised source data, the adoption of improved estimating methods, and for quarterly and monthly measures, the incorporation of updated seasonal factors.

Major source data

The major source data incorporated as part of this year's update are summarized in table 1, and additional information on the NIPA components affected by the incorporation of newly available and revised source data is provided in table 13.2

Source data that affected the NIPA components include the following:

- New Census Bureau Service Annual Survey (SAS) data for 2019 and revised data for 2015 through 2018, which replace Census Bureau Quarterly Services Report data for 2019 and previously incorporated SAS data for 2015 through 2018. SAS data most notably impacted estimates of consumer spending for services and private fixed investment in intellectual property products.

- Revised Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tabulations of corporate tax returns for 2017 and new IRS tabulations of tax returns data for 2018 for corporations, sole proprietorships, and partnerships, which affected estimates of corporate profits, proprietors' income, and net interest.

- Newly available Economic Census data for 2017, new Census Bureau Annual Survey of Manufactures (ASM) data for 2018, which replaced Census Bureau monthly industry shipments data, and revised monthly industry shipments data for 2015–2019, all of which impacted estimates of private investment in equipment and inventories.

- New Census Bureau Annual Retail Trade Survey (ARTS) data for 2018, which replaced Census Bureau monthly retail trade survey data, and revised ARTS data for 2015–2017, both of which impacted estimates of consumer spending for goods and private inventory investment.

- Revised Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) data for 2015–2019, which impacted estimates of private and government compensation.

- Revised Department of Agriculture farm statistics for 2015–2019, which impacted estimates of farm output, inventory investment, and proprietors' income.

- Revised BEA International Transactions Accounts (ITAs) data for 1999–2019, which impacted estimates of exports and imports of goods and services and income flows with the rest of the world.

| Agency | Data | Years covered and vintage |

|---|---|---|

| Census Bureau | Annual Capital Expenditures Survey | 2017 (revised) 2018 (new) |

| Annual Wholesale Trade Survey | 2015–2017 (revised) 2018 (new) |

|

| Annual Retail Trade Survey | 2015–2017 (revised) 2018 (new) |

|

| Annual Survey of Manufactures | 2018 (new) | |

| Economic Census | 2017 (new) | |

| Monthly indicators of manufactures, merchant wholesale trade, and retail trade | 2015–2019 (revised) | |

| Service Annual Survey | 2015–2018 (revised) 2019 (new) |

|

| Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances | Fiscal year 2015–2017 (revised) Fiscal year 2018 (new) |

|

| Monthly survey of construction spending (value put in place) | 2015–2019 (revised) | |

| Quarterly Services Survey | 2015–2019 (revised) | |

| American Community Survey | 2018 (new) | |

| Current Population Survey/Housing Vacancy Survey | 2015–2018 (revised) 2019 (new) |

|

| Office of Management and Budget | Federal budget | Fiscal years 2017–2020 |

| Internal Revenue Service | Tabulations of tax returns for corporations | 2017 (revised) 2018 (new) |

| Tabulations of tax returns for sole proprietorships and for partnerships | 2018 (new) | |

| Bureau of Labor Statistics | Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages | 2015–2019 (revised) |

| Occupational Employment Statistics program | 2019 (new) | |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm statistics | 2015–2019 (revised) |

| Bureau of Economic Analysis | International Transactions Accounts | 1999–2019 (revised) |

Methodology improvements

This year's update also reflects methodological changes to BEA's measures.

Services furnished without payment by financial intermediaries. Several changes have improved the accuracy of BEA's measures of services furnished without payment by financial intermediaries.

Beginning with 2015, measures of the imports of these “implicit” services are now included in the NIPAs; previously, only exports of these services were recorded. Additionally, the NIPA measures of both imports and exports of these services are now based directly on the corresponding measures from the ITAs.3 BEA previously derived the export measure in the NIPAs by allocating the total value of the implicit services to domestic sectors and to the rest of the world, based on Federal Reserve Board data on each sector's share of related assets and liabilities.4

BEA also updated its measures of the implicit services provided by commercial banks to include the services produced by international banking facilities (IBFs).5 Previously, BEA did not capture the implicit services produced by these facilities. The new measures are based on the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation's (FDIC) Call Report data on the total assets and liabilities of IBFs. BEA derives a measure of the implicit services they export using FDIC microdata and then deducts the estimated exports from the total to derive the domestic consumption of these services. The result is added to the measure of total implicit financial services provided domestically by commercial banks to obtain a more comprehensive measure of the domestic share of these financial services.

BEA has simplified its allocation to sectors of the implicit financial services associated with depositor services by relying exclusively on Federal Reserve Board (FRB) data on by-sector shares of checkable deposits and currency and of time and savings deposits from the Financial Accounts of the United States. The FRB sectors align well with the Call Report categories underlying the NIPA estimates of these implicit services for commercial banks and savings institutions. Previously, the allocation used a complex combination of data from different sources that did not yield benefits in terms of accuracy and that included some discontinued data.

Additionally, the updated NIPA estimates more accurately measure the implicit services associated with depositors' and borrowers' services by using a reference rate for both resale agreements and repurchase agreements that is better aligned with the maturity structure of these agreements. Resale and repurchase agreements have a shorter maturity than conventional deposits and loans. The NIPAs now use a reference rate that is based on the quarterly average of the daily Secured Overnight Financing Rate published by the New York Federal Reserve Bank.6 Previously, the same reference rate was applied to all assets and liabilities.

Treasury inflation-protected securities. The accuracy and consistency of BEA measures of Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) are improved in the following two ways:7

First, the NIPAs record quarterly and annual federal government payments of interest on TIPS on an accrual basis; the measures are the sum of (1) accrued fixed-rate interest payments on the original principal and (2) accrued interest on the difference between the original principal and an inflation-adjusted measure of the principal. Beginning with 1999, the quarterly measures of TIPS interest are now derived by interpolating measures of annual interest accruals based on data from the Treasury Department's Bureau of Public Debt (BPD). Previously, BEA estimates of the interest payments were derived by aggregating the fixed-rate payments with monthly BPD measures of monthly interest accruals based on monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI)-based adjustments of the principal. The use of an annual accrual period for the BEA measures reduces the volatility of the series caused by the monthly inflation adjustments. Additionally, the annual accrual period more accurately reflects the fact that interest on these securities are paid to TIPS holders biannually, or when the securities mature, rather than monthly.

Second, beginning with 1999, the allocation of annual measures of the interest paid on TIPS to businesses, persons, and the rest of the world consistently includes an adjustment for inflation. Specifically, the gains and losses associated with the inflation adjustment that accrue to foreign holders of U.S. TIPS are now included in the NIPA measures of interest payments to the rest of the world. Previously, the inflation adjustment was allocated only to U.S. businesses and persons, while the allocation to the rest of the world was limited to the fixed-interest portion of TIPS payments. This improvement is consistent with a June 2020 change in the treatment of TIPS interest in BEA's ITAs.8

Consumer spending for video rentals. Beginning with 2019, quarterly measures of personal spending on “video streaming and rentals” are improved by using a 3-month moving average of HarrisX data as an indicator for the DVD rental portion of the measure. The HarrisX data are based on actual consumer costs of DVD rentals and the number of consumers that hold DVD rental subscriptions or that rent DVDs from physical outlets such as Redbox. Previously, the DVD portion of video streaming and rentals used the product of population and price as an indicator.

Updated seasonal factors. As with every annual update of the NIPAs, this year's update includes the incorporation of updated quarterly and monthly seasonal factors that capture changes in seasonal patterns that emerge over time. The updated seasonal factors reflect a mix of data that are seasonally adjusted by source agencies as well as data directly adjusted by BEA.

Presentational improvements

This year's annual update introduces additional detail for private fixed investment in research and development (R&D), a component of investment in intellectual property products. Starting with 2008, NIPA table group 5.6 (Private Fixed Investment in Intellectual Property Products) provides detail on R&D investment expenditures by software publishers, by financial and real estate services, by computer systems design and related services, and by other nonmanufacturing not elsewhere classified. Previously, this detail was included in the single category “all other nonmanufacturing.”

From 2014 to 2019, real GDP increased at an average annual rate of 2.5 percent, an upward revision of 0.1 percentage point from the prior estimate. Measures of current-dollar GDP were revised up for each year; it increased at an average annual rate of 4.1 percent (unrevised from previously published estimates).

Real GDP growth was revised up 0.2 percentage point for 2015, revised up 0.1 percentage point for 2016 and 2018, was unrevised for 2017, and revised down 0.1 percentage point for 2019 (table 2). The revisions to real GDP and its components primarily reflect revisions to current-dollar measures; price measures were not significantly revised.

- For 2015, upward revisions to personal consumption expenditures (PCE), nonresidential fixed investment, and inventory investment and a downward revision to imports (a subtraction in the calculation of GDP), were partly offset by a downward revision to state and local government spending.

- For 2016, a downward revision to imports and upward revisions to exports and PCE were partly offset by downward revisions to nonresidential fixed investment and inventory investment.

- For 2017, downward revisions to inventory investment, nonresidential fixed investment, and federal government spending were offset by upward revisions to state and local government spending, exports, PCE, and residential fixed investment.

- For 2018, upward revisions to inventory investment and to nonresidential fixed investment, a downward revision to imports, and upward revisions to residential fixed investment and state and local government spending were partly offset by a downward revision to PCE.

- For 2019, downward revisions to PCE, inventory investment, state and local government spending, and exports were partly offset by upward revisions to nonresidential fixed investment and federal government spending.

| Share of current-dollar GDP | Change from preceding period | Contribution to percent change in real GDP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percent) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Gross domestic product1 | 100.0 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.2 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 67.9 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| Goods | 21.1 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Durable goods | 7.2 | 7.6 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Nondurable goods | 13.9 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Services | 46.8 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Gross private domestic investment | 17.5 | 5.5 | −1.5 | 3.5 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 1.0 | −0.3 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| Fixed investment | 17.3 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Nonresidential | 13.5 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 6.9 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| Structures | 3.0 | −0.9 | −4.4 | 4.2 | 3.7 | −0.6 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Equipment | 5.8 | 3.0 | −1.7 | 3.2 | 8.0 | 2.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Intellectual property products | 4.7 | 3.8 | 7.6 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Residential | 3.8 | 10.2 | 6.6 | 4.0 | −0.6 | −1.7 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −0.1 |

| Change in private inventories | 0.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.3 | −0.6 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Net exports of goods and services | −2.8 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.8 | −0.2 | −0.2 | −0.3 | −0.2 |

| Exports | 11.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 3.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Goods | 7.6 | −0.4 | 0.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Services | 4.1 | 2.0 | −0.2 | 3.7 | 0.8 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Imports | 14.6 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 1.1 | −0.8 | −0.3 | −0.7 | −0.6 | −0.2 |

| Goods | 11.8 | 5.7 | 1.4 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 0.5 | −0.7 | −0.2 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.1 |

| Services | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 0.4 | 3.7 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 17.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Federal | 6.6 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| National defense | 4.0 | −2.1 | −0.5 | 0.8 | 3.3 | 5.6 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Nondefense | 2.6 | 3.3 | 2.2 | −0.5 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| State and local | 10.9 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Revisions (percentage points) | |||||||||||

| Gross domestic product | ... | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | ... | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −0.1 |

| Gross private domestic investment | ... | 0.6 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 1.2 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Fixed investment | ... | 0.4 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Nonresidential | ... | 0.5 | −0.2 | −0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Residential | ... | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Change in private inventories | ... | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Net exports of goods and services | ... | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Exports | ... | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Imports | ... | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | ... | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Federal | ... | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.5 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| State and local | ... | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

- The estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 1.1.1, contributions are from NIPA table 1.1.2, and shares are from NIPA table 1.1.10.

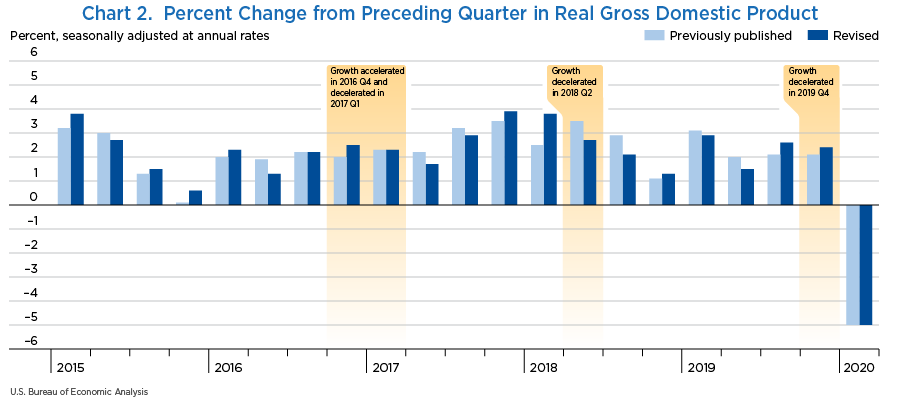

The revisions did not reverse the direction of change in real GDP for any quarter of the revision period (chart 2), and the quarterly pattern for real GDP changed for only 4 of the 21 quarters in the revision period, as highlighted in chart 2. The largest upward revision was 1.3 percentage points for the first quarter of 2018, and the largest downward revision was −0.8 percentage point for the second and third quarters of 2018.

The updated estimates of PCE primarily reflect the incorporation of source data, including newly available and revised Census Bureau SAS data and ARTS data, newly available and revised FRB Financial Accounts of the United States data, and newly available and revised IRS tabulations of corporate and sole proprietors and partnerships tax return data.

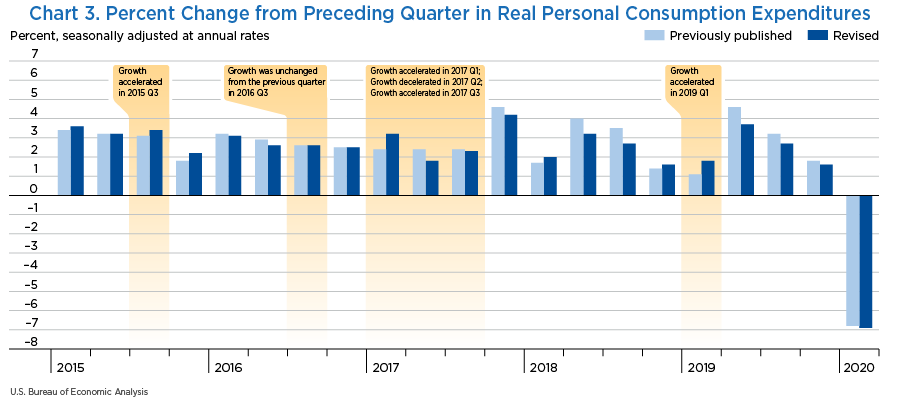

The change in real PCE was revised up 0.1 percentage point for 2015 and 2016, was unrevised for 2017, was revised down 0.3 percentage point for 2018, and was revised down 0.2 percentage point for 2019 (table 3).

- For 2015 and 2016, the revisions were primarily due to upward revisions to services.

- For 2018, the revision was due to downward revisions in services, including health care, food services and accommodations, financial services and insurance, and services provided by nonprofit institutions serving households.

- For 2019, the revision was primarily due to downward revisions in services, including health care, food services and accommodations, recreation services, and services provided by nonprofit institutions serving households.

| Share of current-dollar PCE | Change from preceding period | Contribution to percent change in real PCE | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percent) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Personal consumption expenditures1 | 100.0 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| Goods | 31.0 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Durable goods | 10.5 | 7.6 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 3.6 | 7.6 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 4.3 | −0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Furnishings and durable household equipment | 2.5 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 6.9 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Recreational goods and vehicles | 3.0 | 6.2 | 9.8 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 13.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Other durable goods | 1.5 | 7.8 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Nondurable goods | 20.5 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | 7.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Clothing and footwear | 2.8 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Gasoline and other energy goods | 2.3 | 4.7 | 0.5 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other nondurable goods | 8.3 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Services | 69.0 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Household consumption expenditures (for services) | 66.0 | 3.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Housing and utilities | 18.4 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Health care | 16.9 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Transportation services | 3.3 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Recreation services | 4.0 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Food services and accommodations | 6.9 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Financial services and insurance | 8.1 | 2.4 | −2.0 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 0.2 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Other services | 8.4 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Final consumption expenditures of NPISHs | 3.0 | −2.0 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 3.1 | −3.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Gross output of NPISHs | 11.4 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Less: Receipts from sales of goods and services by NPISHs | 8.4 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Revisions (percentage points) | |||||||||||

| Personal consumption expenditures | ... | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −0.2 |

| Goods | ... | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Durable goods | ... | 0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Nondurable goods | ... | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.3 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 |

| Services | ... | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.4 | −0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.3 | −0.2 |

- NPISHs

- Nonprofit institutions serving households

- The estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 2.3.1, contributions are from NIPA table 2.3.2, and shares are calculated from NIPA table 2.3.5.

The largest upward revision to the quarterly estimates was to the first quarter of 2017; the largest downward revision was to the second quarter of 2019. The quarterly pattern of real PCE is changed for 6 of the 21 quarters of the revision period, as highlighted in chart 3.

Revisions to private fixed investment primarily reflect the incorporation of source data, including revised Census Bureau construction spending (value put in place) data, newly available ASM data, new Economic Census data, and newly available and revised SAS data.

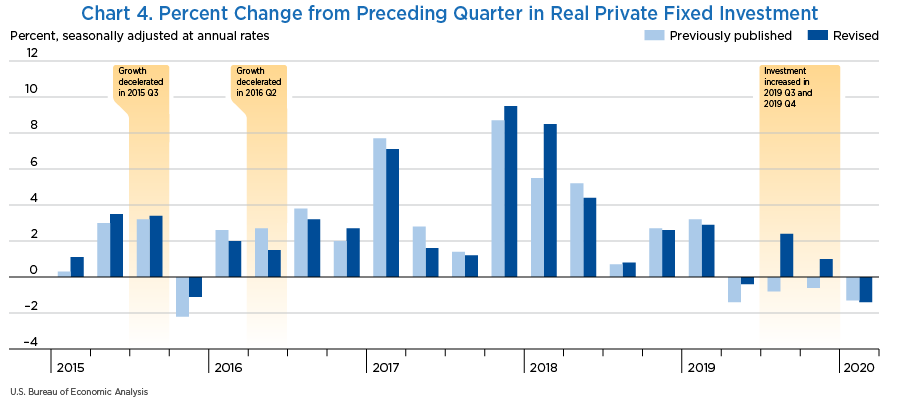

The change in real private fixed investment was revised up 0.4 percentage point for 2015, was revised down 0.1 percentage point for 2016, was revised down 0.4 percentage point for 2017, and was revised up 0.6 percentage point for both 2018 and 2019 (table 4).

- For 2015, the revision was primarily due to an upward revision to nonresidential structures, particularly power and communication structures.

- For 2016, the revision was primarily due to downward revisions to equipment and intellectual property products that were partly offset by an upward revision to nonresidential structures.

- For 2017, the revision was primarily due to a downward revision to equipment that was partly offset by upward revisions to intellectual property products and to residential structures.

- For 2018, the revision was due to upward revisions to equipment, particularly to “other” equipment and industrial equipment, to residential structures, and to intellectual property products.

- For 2019, the revision was due to upward revisions to nonresidential structures, particularly to mining exploration, shafts, and wells and power and communication structures, and to equipment. These upward revisions were partly offset by downward revisions to intellectual property products, particularly software, and to residential structures.

| Share of current-dollar PFI | Change from preceding period | Contribution to percent change in real PFI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percent) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Private fixed investment1 | 100.0 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 1.9 |

| Nonresidential | 78.2 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 6.9 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 2.2 |

| Structures | 17.6 | −0.9 | −4.4 | 4.2 | 3.7 | −0.6 | −0.2 | −0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | −0.1 |

| Commercial and health care | 5.3 | 12.1 | 16.7 | 3.2 | 1.3 | −2.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Manufacturing | 2.1 | 34.4 | −4.9 | −13.4 | −1.8 | 4.6 | 0.7 | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Power and communication | 3.5 | 3.4 | 2.2 | −4.6 | −5.7 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.2 | −0.2 | 0.1 |

| Mining exploration, shafts, and wells | 3.3 | −28.6 | −42.1 | 38.8 | 25.2 | −2.1 | −1.8 | −1.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | −0.1 |

| Other structures | 3.4 | 10.5 | 7.2 | 3.8 | 1.3 | −3.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Equipment | 33.5 | 3.0 | −1.7 | 3.2 | 8.0 | 2.1 | 1.1 | −0.6 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| Information processing equipment | 10.7 | 6.2 | 4.5 | 7.4 | 8.6 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Computers and peripheral equipment | 3.3 | 0.4 | −0.7 | 7.7 | 12.2 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Other | 7.4 | 8.7 | 6.6 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Industrial equipment | 7.0 | 0.1 | −1.4 | 5.5 | 8.2 | 2.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Transportation equipment | 8.4 | 10.5 | −5.8 | −1.6 | 5.8 | −0.4 | 1.0 | −0.6 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Other equipment | 7.4 | −6.6 | −5.6 | 0.6 | 9.6 | 3.5 | −0.6 | −0.4 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Intellectual property products | 27.1 | 3.8 | 7.6 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Software | 11.1 | 4.9 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 11.2 | 7.9 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Research and development | 13.6 | 2.9 | 8.3 | 1.4 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Entertainment, literary, and artistic originals | 2.5 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Residential | 21.8 | 10.2 | 6.6 | 4.0 | −0.6 | −1.7 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 0.9 | −0.1 | −0.4 |

| Structures | 21.4 | 10.2 | 6.6 | 3.9 | −0.6 | −1.8 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | −0.1 | −0.4 |

| Permanent site | 9.4 | 11.8 | 6.5 | 4.4 | 1.8 | −4.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | −0.5 |

| Single family | 7.6 | 11.4 | 5.2 | 6.7 | 2.8 | −6.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | −0.5 |

| Multifamily | 1.8 | 13.4 | 12.2 | −4.7 | −2.1 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other structures | 12.1 | 9.0 | 6.6 | 3.6 | −2.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | −0.3 | 0.1 |

| Equipment | 0.4 | 8.7 | 8.6 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Revisions (percentage points) | |||||||||||

| Private fixed investment | ... | 0.4 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Nonresidential | ... | 0.5 | −0.2 | −0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | −0.2 | −0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Structures | ... | 2.1 | 0.6 | −0.5 | −0.4 | 3.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.7 |

| Equipment | ... | −0.2 | −0.4 | −1.5 | 1.2 | 0.8 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Intellectual property products | ... | 0.2 | −0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | −1.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.3 |

| Residential | ... | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 |

| Structures | ... | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.9 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 |

| Equipment | ... | 0.2 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

- The estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 5.3.1, contributions are from NIPA table 5.3.2, and shares are calculated from NIPA table 5.3.5.

The quarterly pattern of real private fixed investment was changed in 4 of the 21 quarters of the revision period, as highlighted in chart 4. The largest upward revision was for the third quarter of 2019, and the largest downward revisions were for the second quarter of 2016 and the second quarter of 2017.

Revisions to inventory investment primarily reflect Census Bureau data on inventory book values from a number of surveys, including newly available data from the Census Bureau's Economic Census and from its ASM, ARTS, and Annual Wholesale Trade Survey, and from revised monthly inventory data. Revisions also reflect newly available and revised IRS Statistics of Income data and revised data from the Department of Agriculture for farm inventories.

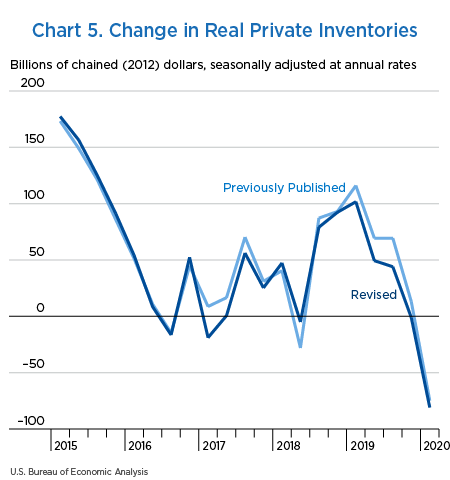

Change in real private inventories, or real inventory investment, was revised up $5.1 billion for 2015, revised up $1.6 billion for 2016, revised down $15.9 billion for 2017, revised up $5.3 billion for 2018, and revised down $18.4 billion for 2019 (table 5; additionally, chart 5 shows quarterly changes).

- For 2015, there were upward revisions to wholesale trade, to retail trade, and to mining, utilities, and construction.

- For 2016, an upward revision to wholesale trade was partly offset by a downward revision to retail trade and smaller downward revisions to manufacturing, to farm, and to mining, utilities, and construction.

- For 2017, the revision was primarily due to a downward revision to manufacturing; other downward revisions were spread across industries.

- For 2018, upward revisions to wholesale trade, to manufacturing, and to retail trade were partly offset by downward revisions to mining, utilities, construction, and to “other” industries.

- For 2019, downward revisions to wholesale trade, to manufacturing, to farm, and to “other” industries were partly offset by upward revisions to retail trade and to mining, utilities, and construction.

| Level | Change from preceding period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Change in private inventories1 | 137.6 | 24.5 | 15.8 | 53.4 | 48.5 | 51.3 | −113.0 | −8.8 | 37.6 | −4.9 |

| Farm | 1.1 | −6.7 | −6.4 | −7.8 | −16.9 | 4.6 | −7.8 | 0.3 | −1.4 | −9.1 |

| Mining, utilities, and construction | 20.1 | 8.2 | −15.1 | −11.8 | 7.2 | 15.5 | −11.9 | −23.3 | 3.3 | 19.0 |

| Manufacturing | 38.4 | −0.9 | −0.5 | 9.3 | 20.7 | 19.9 | −39.3 | 0.4 | 9.8 | 11.4 |

| Durable-goods industries | 18.5 | −10.0 | 0.1 | 11.9 | 14.8 | 2.8 | −28.4 | 10.1 | 11.8 | 2.9 |

| Nondurable-goods industries | 20.3 | 10.5 | −0.7 | −3.3 | 5.5 | 17.8 | −9.8 | −11.2 | −2.6 | 8.8 |

| Wholesale trade | 39.3 | 7.0 | 20.3 | 33.6 | 15.0 | −0.6 | −32.2 | 13.2 | 13.3 | −18.6 |

| Durable-goods industries | 9.6 | 0.5 | 13.7 | 31.2 | 5.0 | −16.3 | −9.1 | 13.2 | 17.5 | −26.3 |

| Nondurable-goods industries | 30.4 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 2.0 | 10.1 | 16.6 | −23.6 | −0.3 | −4.5 | 8.1 |

| Retail trade | 29.7 | 23.8 | 13.4 | 25.9 | 14.4 | 14.2 | −5.9 | −10.5 | 12.6 | −11.5 |

| Motor vehicle and parts dealers | 10.0 | 17.6 | 12.6 | 20.3 | 9.8 | 0.3 | 7.6 | −5.0 | 7.8 | −10.5 |

| Food and beverage stores | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.2 | −0.5 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −0.4 |

| General merchandise stores | 2.8 | −1.0 | −3.3 | 1.8 | −1.4 | 3.9 | −3.8 | −2.3 | 5.1 | −3.2 |

| Other retail stores | 15.0 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 5.5 | 8.7 | −9.1 | −3.0 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Other industries | 9.4 | −8.4 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 5.2 | −2.1 | −17.8 | 10.1 | −0.3 | 3.7 |

| Residual2 | −1.7 | −0.6 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.9 | −1.7 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 0.8 | −0.1 |

| Revisions | ||||||||||

| Change in private inventories | 5.1 | 1.6 | −15.9 | 5.3 | −18.4 | 5.1 | −3.6 | −17.4 | 21.1 | −23.7 |

| Farm | −0.1 | −0.1 | −1.7 | 1.2 | −5.8 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −1.5 | 2.8 | −7.0 |

| Mining, utilities, and construction | 1.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −10.0 | 1.8 | 1.1 | −1.2 | 0.1 | −10.0 | 11.8 |

| Manufacturing | 0.0 | −0.2 | −10.8 | 7.4 | −7.9 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −10.5 | 18.1 | −15.2 |

| Wholesale trade | 2.1 | 3.4 | −3.3 | 7.4 | −10.1 | 2.1 | 1.3 | −6.7 | 10.7 | −17.5 |

| Retail trade | 2.0 | −1.3 | −0.1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2.0 | −3.3 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 0.0 |

| Other industries | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.5 | −3.9 | −0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.5 | −3.4 | 3.1 |

- The levels are from NIPA table 5.7.6B.

- The residual is the difference between the first line and the sum of the most detailed lines.

Note. The chained-dollar series are calculated as the period-to-period change in end-of-period inventories. Because the formula for the chain-type quantity indexes uses weights of more than one period, chained-dollar estimates are usually not additive.

The revisions to the real measures of exports are due to the incorporation of revised data from the ITAs; revisions to exports prices are small. As with the NIPAs, the ITAs are updated each year; the most recent update was released in June 2020 (see “Discontinuities in the Estimates of Foreign Transactions in the National Income and Product Accounts”).9

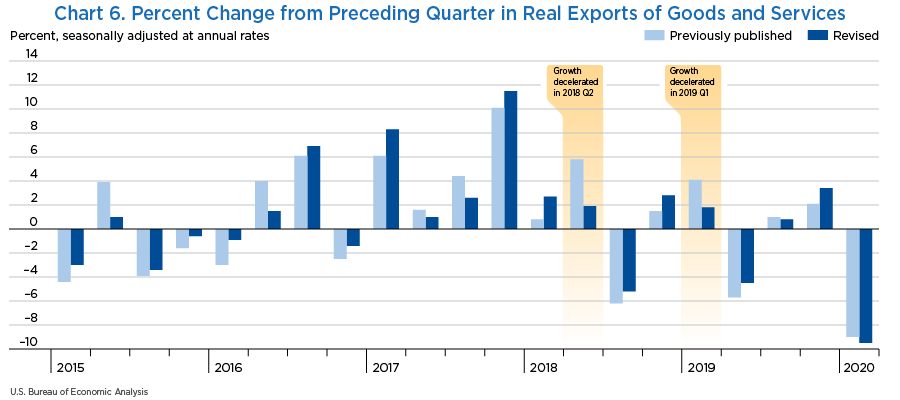

The percent change in real exports was revised up 0.3 percentage point for 2016 and 0.4 percentage point for 2017 (table 6). For 2015 and 2019, revisions to the percent change in real exports were small and downward (−0.1 percentage point); the measure for 2018 was unrevised.

- For 2015, the revision was due to a downward revision to exports of services.

- For 2016 and 2017, the revisions were primarily due to upward revisions to services, particularly other business services and charges for the use of intellectual property not elsewhere classified (n.e.c.). For 2017, the revision was also due to an upward revision to petroleum and products and was partly offset by a downward revision to travel services.

- For 2018, upward revisions to services were offset by downward revisions to goods.

- For 2019, the revision was due to a downward revision to goods that was partly offset by an upward revision to services.

| Share of current-dollar exports | Change from preceding period | Contribution to percent change in real exports | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percent) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Exports of goods and services1 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 3.0 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 3.0 | −0.1 |

| Exports of goods | 65.1 | −0.4 | 0.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | −0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 2.7 | −0.1 |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages | 5.2 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 0.4 | −0.1 | −1.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 |

| Industrial supplies and materials | 21.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 8.7 | 6.7 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| Capital goods, except automotive | 21.8 | −1.3 | −2.1 | 2.5 | 4.6 | −3.2 | −0.3 | −0.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 | −0.7 |

| Automotive vehicles, engines, and parts | 6.5 | −4.9 | −0.2 | 4.7 | −0.2 | 1.9 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Consumer goods, except food and automotive | 8.2 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 3.4 | 3.2 | −0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | −0.1 |

| Other | 2.5 | 6.0 | 7.7 | −4.8 | 4.5 | −3.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Exports of services | 34.9 | 2.0 | −0.2 | 3.7 | 0.8 | −0.1 | 0.7 | −0.1 | 1.3 | 0.3 | −0.1 |

| Transport | 3.6 | −1.4 | −0.1 | 3.8 | 6.7 | −2.3 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 |

| Travel (for all purposes including education) | 7.7 | 1.1 | −0.7 | −1.4 | −0.9 | −3.4 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.3 |

| Charges for the use of intellectual property n.e.c. | 4.7 | −14.6 | 0.9 | 2.6 | −1.7 | −2.8 | −0.8 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 |

| Other business services | 17.2 | 10.7 | 0.6 | 6.8 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Government goods and services n.e.c. | 0.9 | 2.9 | −6.6 | 5.1 | 7.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Other | 0.9 | −4.0 | −9.7 | −1.6 | 1.3 | −3.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Revisions (percentage points) | |||||||||||

| Exports of goods and services | ... | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | −0.1 |

| Exports of goods | ... | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.2 |

| Exports of services | ... | −0.2 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

- The estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 4.2.1, contributions are from NIPA table 4.2.2, and shares are calculated from NIPA table 4.2.5.

The quarterly pattern of real exports is changed for 2 of the 21 quarters in the revision period, as highlighted in chart 6. The largest upward revision was to the first quarter of 2017; the largest downward revision was to the second quarter of 2018.

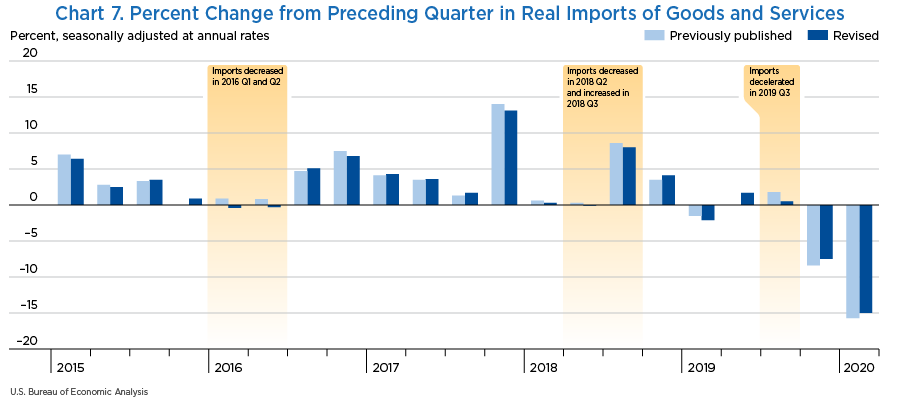

As with exports, the revisions to imports primarily reflect updated data from the ITAs. The percent change in real imports was revised down 0.1 percentage point for 2015, revised down 0.3 percentage point for 2016 and 2018, and revised up 0.1 percentage point for 2019; it was unrevised for 2017 (table 7).

- For 2015, the revision was due to downward revisions to imports of services, particularly travel services and intellectual property products, that were partly offset by an upward revision to other business services.

- For 2016, the revision was due to downward revisions to services, particularly transport services, and to goods.

- For 2018, the revision was due to downward revisions to imports of services, particularly “other” business services, and to goods.

- For 2019, the revision was primarily due to an upward revision to imports of goods, particularly consumer goods except food and automotive, capital goods except automotive, and petroleum and products, that was offset by a downward revision to imports of services, particularly charges for the use of intellectual property n.e.c.

| Share of current-dollar imports | Change from preceding period | Contribution to percent change in real imports | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percent) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Imports of goods and services1 | 100.0 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 1.1 |

| Imports of goods | 80.8 | 5.7 | 1.4 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.4 |

| Foods, feeds, and beverages | 4.8 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 7.8 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Industrial supplies and materials | 16.6 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 0.1 | −5.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | −1.0 |

| Capital goods, except automotive | 21.8 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 9.4 | 8.2 | −0.6 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | −0.1 |

| Automotive vehicles, engines, and parts | 12.1 | 8.4 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Consumer goods, except food and automotive | 21.0 | 9.3 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 |

| Other | 4.5 | 9.9 | 4.2 | 2.8 | −3.4 | 10.9 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 |

| Imports of services | 19.2 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 0.4 | 3.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Transport | 3.4 | 7.3 | −2.8 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Travel (for all purposes including education) | 4.3 | 1.1 | 8.6 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Charges for the use of intellectual property n.e.c. | 1.4 | −16.5 | 18.4 | 3.8 | −3.3 | −4.2 | −0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 |

| Other business services | 8.7 | 7.3 | 1.8 | 4.7 | −3.1 | 5.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | −0.3 | 0.4 |

| Government goods and services n.e.c. | 0.8 | −2.2 | −2.6 | −1.2 | −1.1 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 0.6 | −11.2 | −10.8 | 7.3 | 10.7 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Revisions (percentage points) | |||||||||||

| Imports of goods and services | ... | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.1 |

| Imports of goods | ... | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Imports of services | ... | −0.5 | −1.5 | 0.1 | −1.2 | −0.5 | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −0.1 |

- The estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 4.2.1, contributions are from NIPA table 4.2.2, and shares are calculated from NIPA table 4.2.5.

The quarterly pattern of real imports was changed for 5 of the 21 quarters of the revision period, as highlighted in chart 7. The largest upward revision was to the second quarter of 2019; the largest downward revisions were to the first quarter of 2016 and the third quarter of 2019.

The revisions to the real estimates of state and local government spending primarily reflect revised and newly available source data from Census Bureau surveys of government finances, which are used to estimate most components of spending by state and local governments, revised BLS QCEW data for 2015–2018, and new QCEW data for 2019, which are used to prepare estimates of government compensation, and new Department of Health and Human Services Medical Expenditures Panel Survey data for 2018–2019.

Revisions to federal government spending primarily reflect revisions to revised allocations of Office of Management and Budget (OMB) data from the federal budget for fiscal year (FY) 2017 and FY 2018, revised FY 2019 OMB budget data for 2018 and 2019, and newly available preliminary OMB budget data for FY 2019. Prices were not significantly changed.

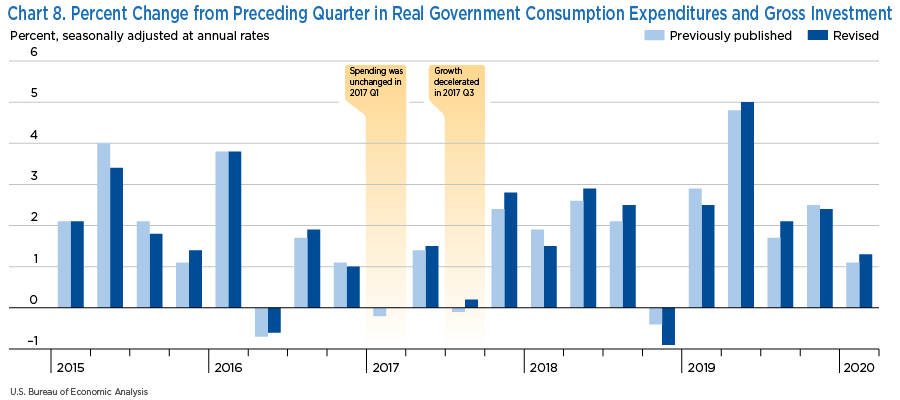

The percent change in real government spending was revised down 0.1 percentage point for 2015, was revised up 0.2 percentage point for 2017, and was revised up 0.1 percentage point for 2018; it was unrevised for 2016 and 2019 (table 8).

- For 2015, the revision was primarily due to a downward revision to state and local government consumption expenditures.

- For 2017 and 2018, the revisions were primarily due to upward revisions to state and local spending that were partly offset by downward revisions to federal government spending.

| Share of current-dollar CEGI | Change from preceding period | Contribution to percent change in real CEGI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percent) | (Percentage points) | ||||||||||

| 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment1 | 100.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 2.3 |

| Consumption expenditures | 79.9 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Gross investment | 20.1 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 4.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Federal | 37.9 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| National defense | 22.7 | −2.1 | −0.5 | 0.8 | 3.3 | 5.6 | −0.5 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| Consumption expenditures | 18.1 | −2.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 4.5 | −0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Gross investment | 4.7 | −1.4 | −2.8 | 3.8 | 7.2 | 9.9 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Nondefense | 15.1 | 3.3 | 2.2 | −0.5 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Consumption expenditures | 11.2 | 3.0 | 1.4 | −1.2 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Gross investment | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| State and local | 62.1 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Consumption expenditures | 50.6 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Gross investment | 11.5 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Revisions (percentage points) | |||||||||||

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | --- | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Federal | --- | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.5 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| National defense | --- | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Nondefense | --- | 0.2 | 0.2 | −1.3 | −0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 0.0 |

| State and local | --- | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | −0.3 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | −0.2 |

- The estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

Note. Percent changes are from NIPA table 3.9.1, contributions are from NIPA table 3.9.2, and shares are calculated from NIPA table 3.9.5.

The revised estimates changed the quarterly pattern of real government spending in 2 of the 21 quarters of the revision period, as highlighted in chart 8. The largest upward revisions were to the fourth quarter of 2017, the third quarter of 2018, and the third quarter of 2019; the largest downward revision was to the second quarter of 2015.

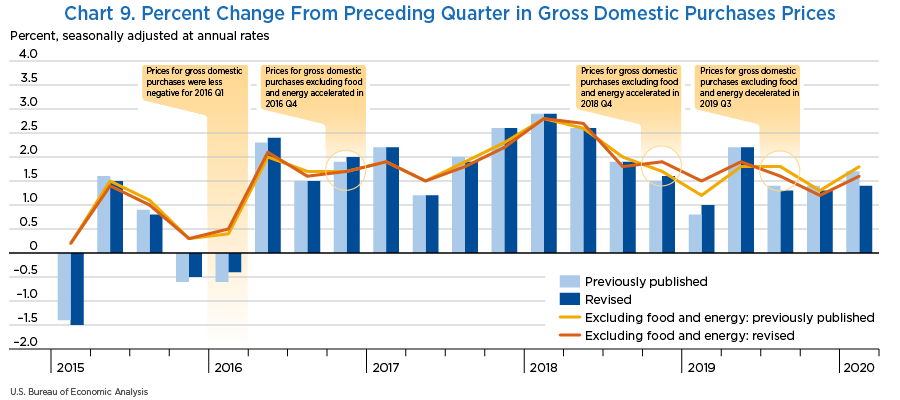

Revisions to BEA's various price measures—such as gross domestic purchases, GDP, and PCE—were small and reflect revised and newly available source data and the regular incorporation of annual weights for the most recent year (2019) (table 9). For the period 2014–2019, the average rate of increase in gross domestic purchases prices was 1.4 percent, the same as previously published.

- The percent change in the gross domestic purchases price index—a measure of the prices paid by consumers, businesses, and governments—was unrevised for 2015–2017, revised down by 0.1 percentage point for 2018, and revised up by 0.1 percentage point for 2019.

- The percent change in GDP prices was unrevised for all years.

- The percent change in PCE prices was unrevised for 2015–2018 and was revised up 0.1 percentage point for 2019.

- From the fourth quarter of 2014 to the first quarter of 2020, the average annual rate of increase in the price index for PCE was unrevised at 1.4 percent. The average annual rate of increase in the “core” PCE price index (which excludes food and energy) was revised up 0.1 percentage point to 1.7 percent.

| Change from preceding period | Contribution to percent change in prices | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Percent) | (Percentage points) | |||||||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Gross domestic purchases1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.6 |

| Personal consumption expenditures | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Goods | −3.1 | −1.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | −0.5 | −0.7 | −0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Durable goods | −2.2 | −2.4 | −2.3 | −1.7 | −1.2 | −0.2 | −0.2 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.1 |

| Nondurable goods | −3.5 | −1.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | −0.1 | −0.5 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Services | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Gross private domestic investment | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Fixed investment | 0.9 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Nonresidential | 0.4 | −0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Structures | 2.1 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Equipment | −0.5 | −1.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Intellectual property products | 0.6 | −1.1 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Residential | 2.7 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 5.6 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Change in private inventories | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Government consumption expenditures and gross investment | 0.2 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Federal | 0.5 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| National defense | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Nondefense | 0.8 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| State and local | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Addenda | ||||||||||

| Gross domestic purchases: | ||||||||||

| Food | 1.1 | −1.1 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Energy goods and services | −18.3 | −7.5 | 8.7 | 8.0 | −2.2 | −0.7 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.1 |

| Excluding food and energy | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| Personal consumption expenditures: | ||||||||||

| Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | 1.1 | −1.0 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Energy goods and services | −17.9 | −7.3 | 8.7 | 8.0 | −2.1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Excluding food and energy | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Gross domestic product (GDP) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.8 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Exports of goods and services | −4.9 | −2.0 | 2.6 | 3.4 | −0.4 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Imports of goods and services | −8.0 | −3.5 | 2.2 | 2.9 | −1.5 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Revisions (percentage points) | ||||||||||

| Gross domestic purchases | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Food | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Energy goods and services | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Excluding food and energy | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| PCE | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Energy goods and services | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Excluding food and energy | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| GDP | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Exports of goods and services | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Imports of goods and services | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

- The estimates under the contribution columns are also percent changes.

Note. Most percent changes are from NIPA table 1.6.7; percent changes for PCE for food and energy goods and services and for PCE excluding food and energy are from NIPA table 2.3.7. Contributions are from NIPA table 1.6.8. GDP, export, and import prices are from NIPA table 1.1.7.

The quarterly patterns of the price indexes for gross domestic purchases and for gross domestic purchases excluding food and energy are generally similar to the pattern reflected by the previously published estimates, as shown in chart 9.

Revisions to the components of national income reflect the incorporation of a variety of newly available and revised source data. For this annual update, major source data include IRS tabulations of tax return data for corporations, for sole proprietorships, and for partnerships, Census Bureau data on government finances, revised OMB federal budget data, FRB data from the Financial Accounts of the United States, revised BLS QCEW data, and revised data from BEA's ITAs.

For measures of income and saving, the annual update extends back to the first quarter of 1999 to incorporate revised measures from the ITAs of income flows between the United States and the rest of the world. Revisions to national income prior to 2015 were small; the revision for 2014 was 0.2 percent, and the largest revision prior to 2014 was .03 percent.

National income was revised down less than 0.1 percent for 2015; it was revised up 0.2 percent for 2016, up 0.9 percent for 2017, up 0.8 percent for 2018, and up 0.6 percent for 2019 (table 10).

- For 2015, the largest downward revisions were to business current transfer payments and taxes on production and imports. The largest offsetting upward revision was to compensation of employees.

- For 2016, upward revisions, particularly to net interest and miscellaneous payments and to corporate profits, were partly offset by downward revisions to business current transfer payments and the current surplus of government enterprises.

- For 2017, upward revisions to corporate profits, net interest and miscellaneous payments, compensation, business current transfer payments, and rental income of persons were partly offset by downward revisions to proprietors' income and the current surplus of government enterprises.

- For 2018, upward revisions to corporate profits, compensation, taxes and production and imports, business current transfer payments, and rental income of persons were partly offset by downward revisions to net interest and miscellaneous payments and proprietors' income.

- For 2019, upward revisions to corporate profits, rental income of persons, compensation, and the current surplus of government enterprises were partly offset by downward revisions to net interest and miscellaneous payments, business current transfer payments, and taxes on production and imports.

| Level | Change from preceding period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| National income | 15,784.6 | 16,082.7 | 16,853.9 | 17,689.6 | 18,269.1 | 544.7 | 298.1 | 771.1 | 835.7 | 579.5 |

| Compensation of employees | 9,699.4 | 9,963.9 | 10,422.5 | 10,950.1 | 11,432.4 | 450.3 | 264.4 | 458.7 | 527.6 | 482.3 |

| Wages and salaries | 7,859.5 | 8,089.1 | 8,471.5 | 8,894.2 | 9,309.3 | 384.3 | 229.6 | 382.3 | 422.7 | 415.1 |

| Government | 1,275.8 | 1,308.2 | 1,347.7 | 1,402.5 | 1,450.8 | 38.9 | 32.4 | 39.5 | 54.8 | 48.3 |

| Other | 6,583.7 | 6,780.9 | 7,123.7 | 7,491.7 | 7,858.5 | 345.4 | 197.2 | 342.8 | 368.0 | 366.8 |

| Supplements to wages and salaries | 1,839.9 | 1,874.7 | 1,951.1 | 2,055.9 | 2,123.1 | 66.1 | 34.8 | 76.3 | 104.8 | 67.2 |

| Employer contributions for employee pension and insurance funds | 1,270.6 | 1,293.5 | 1,346.0 | 1,430.7 | 1,474.0 | 43.1 | 23.0 | 52.4 | 84.7 | 43.3 |

| Employer contributions for government social insurance | 569.4 | 581.2 | 605.1 | 625.2 | 649.1 | 22.9 | 11.8 | 23.9 | 20.1 | 23.9 |

| Proprietors' income with IVA and CCAdj | 1,423.0 | 1,424.8 | 1,509.0 | 1,585.9 | 1,657.7 | −24.8 | 1.8 | 84.2 | 77.0 | 71.7 |

| Farm | 56.2 | 36.0 | 41.5 | 43.0 | 49.7 | −13.6 | −20.2 | 5.5 | 1.5 | 6.6 |

| Nonfarm | 1,366.7 | 1,388.7 | 1,467.4 | 1,542.9 | 1,608.0 | −11.2 | 22.0 | 78.7 | 75.5 | 65.1 |

| Rental income of persons with CCAdj | 649.0 | 682.7 | 721.9 | 759.3 | 787.1 | 44.4 | 33.6 | 39.3 | 37.4 | 27.8 |

| Corporate profits with IVA and CCAdj | 2,060.5 | 2,023.7 | 2,114.5 | 2,243.0 | 2,250.5 | −59.7 | −36.8 | 90.8 | 128.5 | 7.6 |

| Taxes on corporate income | 396.3 | 376.2 | 311.3 | 282.9 | 298.7 | −10.8 | −20.1 | −64.8 | −28.4 | 15.8 |

| Profits after tax with IVA and CCAdj | 1,664.2 | 1,647.6 | 1,803.2 | 1,960.1 | 1,951.8 | −48.9 | −16.6 | 155.6 | 156.9 | −8.3 |

| Net dividends | 1,164.9 | 1,189.4 | 1,270.4 | 1,390.1 | 1,360.8 | 68.8 | 24.5 | 81.0 | 119.7 | −29.3 |

| Undistributed profits with IVA and CCAdj | 499.3 | 458.2 | 532.8 | 570.0 | 591.0 | −117.8 | −41.2 | 74.6 | 37.2 | 21.0 |

| Net interest and miscellaneous payments | 585.8 | 577.3 | 636.4 | 619.1 | 573.4 | 69.7 | −8.5 | 59.1 | −17.3 | −45.7 |

| Taxes on production and imports | 1,275.2 | 1,311.8 | 1,364.0 | 1,444.8 | 1,491.4 | 34.3 | 36.6 | 52.2 | 80.8 | 46.6 |

| Less: Subsidies | 57.2 | 61.7 | 59.9 | 63.3 | 73.9 | −0.9 | 4.6 | −1.9 | 3.4 | 10.6 |

| Business current transfer payments (net) | 154.2 | 164.6 | 150.7 | 156.6 | 158.0 | 23.8 | 10.4 | −13.9 | 5.9 | 1.4 |

| To persons (net) | 50.3 | 59.7 | 48.8 | 47.4 | 47.2 | 7.3 | 9.4 | −10.8 | −1.5 | −0.2 |

| To government (net) | 110.5 | 105.5 | 99.6 | 101.0 | 89.1 | 12.4 | −5.1 | −5.8 | 1.4 | −11.9 |

| To the rest of the world (net) | −6.6 | −0.5 | 2.2 | 8.2 | 21.7 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 2.7 | 6.0 | 13.5 |

| Current surplus of government enterprises | −5.3 | −4.3 | −5.3 | −5.8 | −7.6 | 5.7 | 0.9 | −0.9 | −0.6 | −1.8 |

| Revisions | ||||||||||

| National income | −3.2 | 29.1 | 145.0 | 143.7 | 107.0 | −0.7 | 32.3 | 115.9 | −1.4 | −36.6 |

| Compensation of employees | 1.3 | 3.5 | 10.9 | 21.6 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 7.4 | 10.7 | −16.9 |

| Proprietors' income with IVA and CCAdj | 0.8 | 1.1 | −9.2 | −2.8 | −0.6 | 0.8 | 0.3 | −10.3 | 6.4 | 2.3 |

| Rental income of persons with CCAdj | 0.9 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 9.2 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.9 | −0.6 | 6.7 |

| Corporate profits with IVA and CCAdj | −1.0 | 12.3 | 108.6 | 168.3 | 175.9 | −1.0 | 13.3 | 96.3 | 59.8 | 7.5 |

| Net interest and miscellaneous payments | −1.0 | 17.3 | 28.4 | −53.6 | −71.5 | −1.0 | 18.3 | 11.1 | −81.9 | −18.0 |

| Taxes on production and imports | −2.0 | −1.0 | −0.5 | 3.0 | −3.4 | −2.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 3.5 | −6.4 |

| Less: Subsidies | −0.1 | −0.1 | −1.3 | −1.1 | −0.9 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −1.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Business current transfer payments (net) | −2.5 | −3.6 | 5.3 | 2.9 | −12.7 | 0.0 | −1.0 | 8.9 | −2.4 | −15.6 |

| Current surplus of government enterprises | 0.3 | −1.7 | −2.8 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 0.3 | −2.0 | −1.0 | 3.4 | 3.9 |

- CCADj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment

Note. Dollar levels are from NIPA table 1.12.

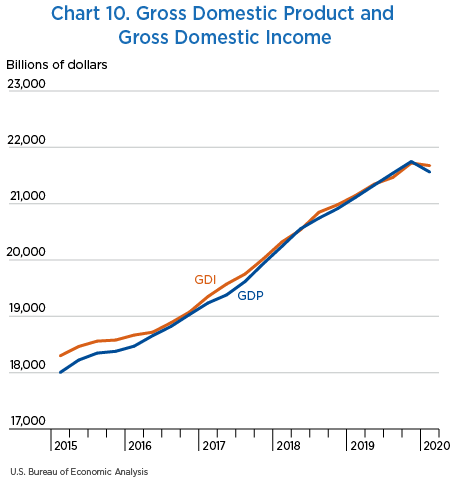

Current-dollar GDI was revised down by less than 0.1 percent for 2015 and up by less than 0.1 percent for 2016; it was revised up by 0.4 percent for 2017 and 2019; and it was revised up by 0.5 percent for 2018. Current-dollar GDP is revised by less than 0.1 percent for 2015 and 2019 and by more than 0.1 percent for 2016–2018 (table 11 and chart 10).

The percent change in real GDI was unrevised for 2015, revised up 0.1 percentage point for 2016, revised up 0.4 percentage point for 2017, revised up 0.1 percentage point for 2018, and revised down 0.1 percentage point for 2019. From 2014 to 2019, the average of real GDI and real GDP increased at an average annual rate of 2.3 percent, up 0.1 percentage point from the previously published estimates.

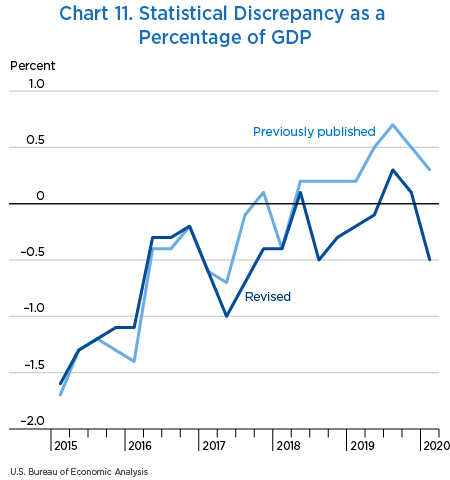

The statistical discrepancy—current-dollar GDP less current-dollar GDI as a percentage of GDP—was −1.3 percent for 2015, −0.5 percent for 2016, −0.7 percent for 2017, −0.3 percent for 2018, and 0.1 percent for 2019 (table 11); the quarterly pattern of the statistical discrepancy is provided in chart 11.

| Level | Change from preceding period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Gross domestic product | 18,238.3 | 18,745.1 | 19,543.0 | 20,611.9 | 21,433.2 | 711.0 | 506.8 | 797.9 | 1,068.9 | 821.4 |

| Less: Statistical discrepancy | −237.3 | −92.2 | −131.4 | −58.0 | 12.8 | 49.3 | 145.1 | −39.3 | 73.4 | 70.8 |

| Equals: Gross domestic income | 18,475.6 | 18,837.3 | 19,674.4 | 20,669.9 | 21,420.4 | 661.7 | 361.6 | 837.2 | 995.4 | 750.5 |

| Plus: Income receipts from the rest of the world | 860.8 | 893.5 | 1,032.7 | 1,142.9 | 1,169.8 | 7.2 | 32.8 | 139.2 | 110.1 | 27.0 |

| Less: Income payments to the rest of the world | 640.4 | 661.5 | 740.4 | 858.2 | 900.2 | 27.9 | 21.1 | 79.0 | 117.7 | 42.1 |

| Equals: Gross national income | 18,696.0 | 19,069.3 | 19,966.7 | 20,954.6 | 21,690.0 | 641.1 | 373.3 | 897.4 | 987.9 | 735.4 |

| Less: Consumption of fixed capital | 2,911.4 | 2,986.6 | 3,112.9 | 3,265.0 | 3,420.9 | 96.4 | 75.2 | 126.3 | 152.2 | 155.9 |

| Equals: National income | 15,784.6 | 16,082.7 | 16,853.9 | 17,689.6 | 18,269.1 | 544.7 | 298.1 | 771.1 | 835.7 | 579.5 |

| Less: | ||||||||||

| Corporate profits with IVA and CCAdj | 2,060.5 | 2,023.7 | 2,114.5 | 2,243.0 | 2,250.5 | −59.7 | −36.8 | 90.8 | 128.5 | 7.6 |

| Taxes on production and imports less subsidies | 1,218.0 | 1,250.0 | 1,304.1 | 1,381.5 | 1,417.5 | 35.2 | 32.1 | 54.1 | 77.4 | 36.1 |

| Contributions for government social insurance, domestic | 1,204.7 | 1,239.1 | 1,298.4 | 1,360.4 | 1,418.8 | 51.2 | 34.3 | 59.3 | 62.0 | 58.4 |

| Net interest and miscellaneous payments on assets | 585.8 | 577.3 | 636.4 | 619.1 | 573.4 | 69.7 | −8.5 | 59.1 | −17.3 | −45.7 |

| Business current transfer payments (net) | 154.2 | 164.6 | 150.7 | 156.6 | 158.0 | 23.8 | 10.4 | −13.9 | 5.9 | 1.4 |

| Current surplus of government enterprises | −5.3 | −4.3 | −5.3 | −5.8 | −7.6 | 5.7 | 0.9 | −0.9 | −0.6 | −1.8 |

| Plus: Personal income receipts on assets | 2,472.2 | 2,551.7 | 2,738.5 | 2,946.7 | 2,967.9 | 169.9 | 79.6 | 186.8 | 208.2 | 21.2 |

| Plus: Personal current transfer receipts | 2,685.4 | 2,776.8 | 2,855.1 | 2,970.3 | 3,125.2 | 143.9 | 91.4 | 78.3 | 115.2 | 154.9 |

| Equals: Personal income | 15,724.2 | 16,160.7 | 16,948.6 | 17,851.8 | 18,551.5 | 732.5 | 436.5 | 787.9 | 903.2 | 699.7 |

| Revisions | ||||||||||

| Gross domestic product | 13.5 | 30.0 | 23.6 | 31.6 | 5.5 | 13.5 | 16.5 | −6.5 | 8.1 | −26.1 |

| Statistical discrepancy | 17.6 | 19.8 | −63.9 | −68.8 | −85.4 | 15.1 | 2.2 | −83.7 | −4.9 | −16.6 |

| Gross domestic income | −4.1 | 10.3 | 87.4 | 100.4 | 90.9 | −1.5 | 14.3 | 77.2 | 13.0 | −9.5 |

- CCADj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment

Note. Dollar levels are from NIPA table 1.12.

Most of the components of personal income are also components of national income and of GDI, and the revisions reflect the incorporation of much of the same newly available and revised source data, including tabulations of tax return data from the IRS, FRB data from the Financial Accounts of the United States, and wage and salary data from BLS' QCEW.

Personal income was revised up for 2015–2018; it was revised down for 2019 (table 12).

- For 2015, the revision was primarily due to upward revisions to personal current transfer receipts, compensation, and personal interest income; these were partly offset by a downward revision to employer contributions for employee pension and insurance funds.

- For 2016, the revision was primarily due to upward revisions to personal interest income and personal dividend income; compensation and personal current transfer receipts also contributed.

- For 2017, the upward revision was primarily due to upward revisions to personal dividend income and personal interest income; upward revisions to compensation and to personal current transfer receipts also contributed. These revisions were partly offset by a downward revision to proprietors' income.

- For 2018, the primary contributors to the upward revision were personal dividend income and compensation; downward revisions to personal interest income and to proprietors' income partly offset these impacts.

- For 2019, the revision primarily reflected downward revisions to personal current transfer receipts, particularly Medicare and Medicaid, and to personal interest income; these were partly offset by upward revisions to personal dividend income, rental income, and compensation.

- Personal saving was revised down for 2015 and 2019. For 2015, personal outlays were revised up by more than personal income; for 2019, personal income was revised down, and personal taxes were revised up. For 2016 and 2017, personal saving was revised up, as upward revisions to income more than offset upward revisions to outlays and taxes. For 2018, upward revisions to income more than offset the upward revision to taxes.

- The personal saving rate (personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income) was revised down to 7.5 percent in 2015, revised up to 6.9 percent in 2016, revised up to 7.2 percent in 2017, revised up to 7.8 percent in 2018, and revised down to 7.5 percent in 2019 (a downward revision of 0.4 percentage point).

- For the first quarter of 2015 through the first quarter of 2020, the personal saving rate was revised up for 10 quarters, revised down for 10 quarters, and was unrevised for 1 quarter. The average quarterly saving rate over this period was unrevised at 7.5 percent.

| Level | Change from preceding period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Personal income | 15,724.2 | 16,160.7 | 16,948.6 | 17,851.8 | 18,551.5 | 732.5 | 436.5 | 787.9 | 903.2 | 699.7 |

| Compensation of employees | 9,699.4 | 9,963.9 | 10,422.5 | 10,950.1 | 11,432.4 | 450.3 | 264.4 | 458.7 | 527.6 | 482.3 |

| Wages and salaries | 7,859.5 | 8,089.1 | 8,471.5 | 8,894.2 | 9,309.3 | 384.3 | 229.6 | 382.3 | 422.7 | 415.1 |

| Private industries | 6,583.7 | 6,780.9 | 7,123.7 | 7,491.7 | 7,858.5 | 345.4 | 197.2 | 342.8 | 368.0 | 366.8 |

| Government | 1,275.8 | 1,308.2 | 1,347.7 | 1,402.5 | 1,450.8 | 38.9 | 32.4 | 39.5 | 54.8 | 48.3 |

| Supplements to wages and salaries | 1,839.9 | 1,874.7 | 1,951.1 | 2,055.9 | 2,123.1 | 66.1 | 34.8 | 76.3 | 104.8 | 67.2 |

| Proprietors' income with IVA and CCAdj | 1,423.0 | 1,424.8 | 1,509.0 | 1,585.9 | 1,657.7 | −24.8 | 1.8 | 84.2 | 77.0 | 71.7 |

| Farm | 56.2 | 36.0 | 41.5 | 43.0 | 49.7 | −13.6 | −20.2 | 5.5 | 1.5 | 6.6 |

| Nonfarm | 1,366.7 | 1,388.7 | 1,467.4 | 1,542.9 | 1,608.0 | −11.2 | 22.0 | 78.7 | 75.5 | 65.1 |

| Rental income of persons with CCAdj | 649.0 | 682.7 | 721.9 | 759.3 | 787.1 | 44.4 | 33.6 | 39.3 | 37.4 | 27.8 |

| Personal income receipts on assets | 2,472.2 | 2,551.7 | 2,738.5 | 2,946.7 | 2,967.9 | 169.9 | 79.6 | 186.8 | 208.2 | 21.2 |

| Personal interest income | 1,439.1 | 1,474.3 | 1,577.6 | 1,641.6 | 1,677.4 | 90.1 | 35.2 | 103.4 | 63.9 | 35.8 |

| Personal dividend income | 1,033.1 | 1,077.4 | 1,160.8 | 1,305.1 | 1,290.4 | 79.9 | 44.4 | 83.4 | 144.2 | −14.6 |

| Personal current transfer receipts | 2,685.4 | 2,776.8 | 2,855.1 | 2,970.3 | 3,125.2 | 143.9 | 91.4 | 78.3 | 115.2 | 154.9 |

| Government social benefits to persons | 2,635.1 | 2,717.1 | 2,806.2 | 2,922.9 | 3,078.0 | 136.5 | 82.0 | 89.1 | 116.7 | 155.1 |

| Other current transfer receipts, from business (net) | 50.3 | 59.7 | 48.8 | 47.4 | 47.2 | 7.3 | 9.4 | −10.8 | −1.5 | −0.2 |

| Less: Contributions for government social insurance | 1,204.7 | 1,239.1 | 1,298.4 | 1,360.4 | 1,418.8 | 51.2 | 34.3 | 59.3 | 62.0 | 58.4 |

| Less: Personal current taxes | 1,939.9 | 1,957.9 | 2,046.7 | 2,085.3 | 2,202.9 | 155.4 | 17.9 | 88.8 | 38.6 | 117.6 |

| Equals: Disposable personal income (DPI) | 13,784.3 | 14,202.8 | 14,901.9 | 15,766.5 | 16,348.6 | 577.2 | 418.5 | 699.0 | 864.7 | 582.1 |

| Less: Personal outlays | 12,745.6 | 13,227.8 | 13,830.9 | 14,529.2 | 15,117.4 | 509.4 | 482.2 | 603.1 | 698.3 | 588.2 |

| Equals: Personal saving | 1,038.7 | 975.0 | 1,071.0 | 1,237.3 | 1,231.2 | 67.7 | −63.7 | 95.9 | 166.3 | −6.1 |

| Personal saving as a percentage of DPI (percent) | 7.5 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 0.1 | −0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 | −0.3 |

| Revisions | ||||||||||

| Personal income | 6.5 | 39.5 | 69.8 | 32.7 | −56.8 | 6.5 | 33.1 | 30.3 | −37.1 | −89.5 |

| Less: Personal current taxes | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 7.6 | 19.7 | 1.6 | −0.4 | −0.9 | 6.7 | 12.1 |

| Equals: DPI | 4.3 | 37.7 | 68.9 | 25.0 | −76.5 | 4.9 | 33.4 | 31.1 | −43.8 | −101.6 |

| Less: Personal outlays | 14.4 | 21.5 | 28.8 | −1.9 | −4.9 | 15.2 | 7.1 | 7.3 | −30.7 | −3.0 |

| Equals: Personal saving | −10.1 | 16.2 | 40.1 | 26.9 | −71.6 | −10.3 | 26.3 | 23.8 | −13.1 | −98.5 |

| Personal saving as a percentage of DPI (percentage points) | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.4 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.5 |

- CCADj

- Capital consumption adjustment

- IVA

- Inventory valuation adjustment

Note. Dollar levels are from NIPA table 2.1.

Table 13 presents the updated NIPA components with revisions of $5.0 billion or more (in absolute value) and lists the major source data that were incorporated as part of this year's update. Note that the incorporation of newly available and revised source data for a given year usually results in a revision to the level of an estimate both for that year and for subsequent years.

| Line | NIPA component and major source data incorporated1 | Billions of dollars | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revision in level | Level | ||||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2019 | ||

| 1 | Gross domestic product | 13.5 | 30.0 | 23.6 | 31.6 | 5.5 | 21,433.2 |

| 2 | Personal consumption expenditures | 13.2 | 21.5 | 28.3 | −5.4 | −18.1 | 14,544.6 |

| 3 | Goods | 2.7 | 2.4 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 4,512.2 |

| 4 | Durable goods | 1.7 | −2.4 | −1.9 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 1,534.4 |

| 5 | Motor vehicles and parts | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 | −9.3 | 521.8 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 6 | Net purchases of used motor vehicles

Revised trade source data on cars and trucks in operation for 2015–2018; new Census Bureau Annual Retail Trade Survey (ARTS) data for retail and wholesale margins for 2018; new trade source data on cars and trucks in operation for 2019; revised Census Bureau Monthly Retail Trade Survey (MRTS) and Monthly Wholesale Trade Report data on retail sales and wholesale sales of used motor vehicle dealers for 2019. |

1.0 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 4.3 | −6.3 | 158.5 |

| 7 | Furnishings and durable household equipment | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 3.8 | 357.4 |

| 8 | Recreational goods and vehicles | 0.5 | −5.3 | −4.6 | 4.4 | 15.6 | 433.4 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 9 | Video, audio, photographic, and information processing equipment and media

Revised ARTS data for 2016–2017; new ARTS data for 2018; revised MRTS data for 2019; revised trade source retail scanner data for 2017–2018; new trade source retail scanner data for 2019; Census e-commerce report for 2015–2018; revised trade source data on prerecorded discs, vinyl, and permanent digital downloads for 2018; new trade source data on prerecorded discs, vinyl, and permanent digital downloads for 2019. |

0.5 | −4.5 | −3.7 | 1.8 | 11.3 | 256.3 |

| 10 | Other durable goods | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.2 | −2.3 | −2.5 | 221.7 |

| 11 | Nondurable goods | 0.9 | 4.9 | 9.1 | 1.1 | −0.3 | 2,977.9 |

| 12 | Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.7 | −4.6 | −6.5 | 1,025.7 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 13 | Food and nonalcoholic beverages purchased for off-premises consumption

Revised ARTS data for 2016–2017; new ARTS data for 2018; revised MRTS data for 2019; revised trade source retail scanner data for 2018; new trade source retail scanner data for 2019. |

0.8 | 1.6 | 2.3 | −5.5 | −8.6 | 878.1 |

| 14 | Clothing and footwear | −0.1 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 403.5 |

| 15 | Gasoline and other energy goods | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | −0.4 | −2.3 | 335.4 |

| 16 | Other nondurable goods | 0.1 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 1,213.3 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 17 | Recreational items

Revised ARTS data for 2016–2017; new ARTS data for 2018; revised MRTS data for 2019; Census e-commerce report for 2015–2018. |

−0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 183.2 |

| 18 | Services | 10.5 | 19.0 | 21.1 | −12.5 | −25.3 | 10,032.4 |

| 19 | Household consumption expenditures (for services) | 10.4 | 15.8 | 18.1 | −8.3 | −19.1 | 9,593.2 |

| 20 | Housing and utilities | 2.2 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 10.8 | 2,681.2 |

| 21 | Housing | 2.2 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 7.2 | 2,330.6 |

| 22 | Household utilities | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 350.6 |

| 23 | Health care | 0.1 | 5.0 | 4.9 | −7.6 | −19.2 | 2,450.8 |

| 24 | Outpatient services | 0.1 | 5.1 | 8.9 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1,104.2 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 25 | Physician services

Revised Census Bureau Service Annual Survey (SAS) taxable and tax-exempt revenue data for 2015 through 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

0.0 | 1.7 | 1.5 | −0.8 | −5.1 | 572.0 |

| 26 | Paramedical services

Revised SAS taxable revenue data for 2015 through 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

0.1 | 3.6 | 7.1 | 5.0 | 8.9 | 397.4 |

| 27 | Hospital and nursing home services | 0.1 | −0.1 | −4.0 | −10.8 | −21.1 | 1,346.6 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 28 | Nursing homes

Revised SAS taxable and tax-exempt revenue data for 2015 and 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −6.8 | −17.9 | 190.1 |

| 29 | Transportation services | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 483.4 |

| 30 | Motor vehicle services | 0.1 | −0.8 | −2.1 | −3.0 | −5.5 | 306.0 |

| 31 | Public transportation | 0.0 | 1.2 | 3.0 | 7.4 | 10.7 | 177.4 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 32 | Air transportation

Revised SAS taxable revenue data for 2015 through 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

0.0 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 5.9 | 114.7 |

| 33 | Recreation services | −0.4 | −1.3 | −1.4 | −1.4 | −7.4 | 580.4 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 34 | Membership clubs, sports centers, parks, theaters, and museums

Revised SAS taxable and tax-exempt revenue data for 2015 through 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

−0.2 | 0.2 | −1.5 | −2.1 | −6.2 | 218.2 |

| 35 | Food services and accommodations | 0.0 | 0.8 | −0.1 | −12.1 | −19.5 | 999.5 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 36 | Food services | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.7 | −11.3 | −19.2 | 843.2 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 37 | Purchased meals and beverages

Revised SAS taxable revenue data for 2015 through 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

0.0 | 0.0 | −0.7 | −11.3 | −19.1 | 820.7 |

| 38 | Financial services and insurance | 0.4 | 6.4 | 12.0 | 8.5 | 19.0 | 1,176.1 |

| 39 | Financial services | 0.2 | 6.4 | 4.3 | −4.5 | −4.5 | 733.4 |

| 40 | Financial services furnished without payment

Revised Federal Reserve Board (FRB) Financial Accounts of the United States data for 2015 to 2018; new FRB data for 2019; revised Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tabulations of corporate tax return data for 2017; new IRS tabulations of corporate and of sole proprietorship and partnership tax return data for 2018; new Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation data for 2019; new trade source data on credit unions and on investment companies for 2019. |

2.3 | 8.3 | 15.4 | 13.9 | 16.4 | 370.0 |

| 41 | Financial service charges, fees, and commissions

Revised SAS taxable revenue data for 2015 through 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

−2.1 | −1.9 | −11.0 | −18.3 | –20.9 | 363.4 |

| 42 | Insurance | 0.2 | 0.1 | 7.6 | 13.0 | 23.5 | 442.7 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 43 | Life insurance

Revised and newly available trade source data on life insurance company expenses for 2017 and 2018; new Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Qarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) data for 2019. |

0.0 | 0.0 | 7.8 | 9.1 | 13.4 | 99.6 |

| 44 | Net health insurance

Revised benefits-to premiums ratio based on new trade source data on medical insurance for 2018; new Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data for 2019. |

0.1 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 245.7 |

| 45 | Other services | 8.0 | 1.2 | −2.7 | −3.1 | −8.0 | 1,221.8 |

| Of which: | |||||||

| 46 | Education services | 1.2 | 0.8 | −3.0 | −4.5 | −6.1 | 299.6 |

| 47 | Social services and religious activities

Revised SAS taxable and tax-exempt revenue data for 2015 through 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −7.1 | 212.4 |

| 48 | Net foreign travel2 | 6.7 | 0.2 | 1.3 | −0.9 | 6.1 | −14.0 |

| 49 | Foreign travel by U.S. residents

Revised Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) International Transactions Accounts (ITAs) data for 2015–2019. |

−8.0 | −14.0 | −16.0 | −19.6 | −17.1 | 181.8 |

| 50 | Less: Expenditures in the United States by nonresidents

Revised BEA ITAs data for 2015–2019. |

−14.7 | −14.2 | −17.3 | −18.7 | −23.2 | 195.8 |

| 51 | Final consumption expenditures of nonprofit institutions serving households | 0.2 | 3.2 | 2.9 | −4.2 | −6.2 | 439.2 |

| 52 | Gross output of nonprofit institutions

Revised SAS tax-exempt expenses data for 2015 through 2018; new SAS data for 2019. |

0.0 | 3.3 | 1.8 | −0.9 | −14.2 | 1,658.1 |

| 53 | Less: Receipts from sales of goods and services by nonprofit institutions